INTRODUCTION

As the novel coronavirus sweeps around the world, public health systems and political leaders in every country are put to the test – literally in the case of testing capacity and figuratively in the case of decision making, communications and directions.

This is a succinct look at how Australia and the United States are tackling the coronavirus pandemic, comparing and contrasting the approaches taken on some key issues.

1. PREPARATION AND ORGANISATION

The ability to respond to an emerging epidemic with the necessary agility, expertise and coordination requires sustained investment in preparation and prevention. Because the public is usually blind to these activities, they deliver few rewards to governments. So too often they are subject to cuts that curtail their effectiveness.

In the United States, the Trump administration has consistently pushed for substantial cuts in the budgets of the agencies charged with protecting public health. The US Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, which delivers health and related services in under-served areas and is now seen as an essential driver of the response to coronavirus, has been allowed to erode. Most egregiously, President Trump undermined the national ability to respond in a coordinated fashion by dismantling the global health security unit of the White House’s National Security Council. Now the United States is paying the price.

Trump’s approach seems to have been along the lines of “Just in Time” principles: buy in or get back the resources as they needed rather than any long-term investment (he has reportedly also tried to apply this approach with vaccine development). The lack of stable and experienced leadership in the White House mattered. It was weeks before the White House Coronavirus Task Force was established. Even now it is not certain who is leading this effort as the voices and opinions of President Trump, Vice President Pence, and Health and Human Services Secretary Azar compete with those of the experts.

In contrast, Australia has made the investment in preparation with the development, regular updating and testing of a series of national pandemic action plans. This work is done under the auspices of the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC), which reports to the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. More recently a national cabinet, chaired by the Prime Minister, has been set up to help coordinate federal and state government initiatives more broadly.

Theoretically, Dr Brendan Murphy, as Chief Medical Officer of Australia, chair of the AHPPC, and anointed new head of the Department of Health, is the nation’s spokesperson on health issues. However, there have been several instances where there have been contradictory or confusing messages when politicians have strayed into this arena.

Both countries have been slow to put out messages and guidance for the general public, adding to their anxiety and confusion.

2. READY AND AFFORDABLE ACCESS TO NEEDED SERVICES

The coronavirus epidemic has cast a merciless light on the deficiencies of the US healthcare system and other social supports, such as paid sick leave. Legislative action is needed to increase the number of people covered for testing, treatment, sick leave, quarantine time and loss of employment. The current proposal in the House of Representatives does not adequately cover millions of Americans, including many of the most vulnerable. The shutdowns and other mechanisms required to limit the spread of the virus will mean economic disaster for many.

Australia cannot be too smug about the robustness of its health and social safety net; there are many hurdles to accessing services and many holes for the vulnerable to fall through. For example, combining self-employed individual and casual workers, 37 per cent of Australian workers have no access to paid sick leave. As others have pointed out, coronavirus is already exposing these cracks in Australia’s healthcare system, which has long needed reforms in primary care.

New models of testing, quarantine and care delivery are needed in Australia. It makes little sense for general practitioners to be conducting screening clinics, regardless of where these are held – that can be done by nurses. Experience with H1N1, commonly known as Swine Flu, highlights that GPs are needed for vital clinical roles in the community. We need quarantine solutions that offer alternatives to sending people who might be are positive (including healthcare professionals treating patients) home to healthy family members.

Both countries are pushing the value of telehealth medicine at this time but given the limited uptake of this in both Australia and the United States, it’s a gamble that this emergency situation will change doctors’ and patients’ behaviours.

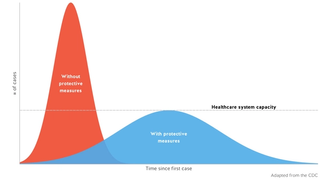

Hospitals will struggle to care for the sickest unless efforts to “flatten the curve” are successful. Their ability to cope depends on the healthcare workforce. It is imperative that healthcare workers, on the frontlines of infection every day, are given the support and resources they desperately need. Supplies of personal protection equipment are already inadequate and certain to get worse.

Finally, efforts to limit the spread of the virus by getting people to work from home and students to do their classwork online highlight the digital divide and how essential connectivity and good broadband systems are. Australia’s broadband system is seriously inadequate for such tasks. At the same time, an estimated 21 million Americans, mostly in rural areas, don’t have access to high-speed broadband.

3. ATTENTION TO SOCIAL INEQUALITIES

The coronavirus pandemic is the perfect example of how the privileged cannot wall themselves off from others’ misfortunes. Research on influenza shows that poverty and inequality exacerbate rates of transmission and mortality for everyone. There are valid fears that the pandemic is widening the social and economic divisions that also make infection deadlier. These inequalities don’t just play out in terms of access to testing and healthcare, they also influence ability to take time off work and to purchase and stockpile essential items to survive quarantine and illness.

The failure of both countries to address these issues – for the poor, for First Nations people, the homeless and the incarcerated, the disabled, and asylum seekers and the undocumented – will have health and social consequences for years to come. In Australia, Pat Turner, CEO of the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, has warned that if coronavirus gets into Indigenous communities in Australia, “it will be absolute devastation” and called for greater support and resources.

4. LEARNING FROM OR IGNORING THE PAST

In the wake of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, there was a plethora of papers about the lessons learned – many of them done or commissioned by the government agencies involved. In Australia, there seems to have been an effort (albeit incomplete) to incorporate findings from the health sector response into the current efforts. Sadly, the recommendations relating to workforce capacity have been ignored, perhaps because in 2014 the Australian government abolished the health workforce agency that would have done this work. It is also worth noting that the report found the effectiveness of border measures difficult to assess and the public health benefits unclear.

In the United States, the various analyses from the Government Accountability Office, the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Department of Homeland Security have apparently been buried along with other Obama-era reports. Other potential resources have also been ignored. For example, in 2012-13 Health and Human Services invested some US$670 million in four manufacturing complexes that planned to work with private companies and universities to deliver emergency medicines and vaccines. Trump officials, however, deemed these ill-suited to current needs.

GOING FORWARD

A pandemic inevitably means that countries look inwards to their own needs. President Trump’s policies have exaggerated the extent to which this is the case in the United States. Now the exigencies of the time, exacerbated by lack of forward planning in some cases, mean that many countries are facing shortages of essential testing reagents and kits as well as medical equipment.

In the weeks ahead, will the world be willing to share resources, as China has done for Italy? Or will there be isolationism, as seen in the accusations that the Trump administration is seeking to buy a German vaccine “only for the United States”? And at the personal level, will there be supermarket fights over toilet paper and a rush for the well-to-do to get tested, or will communities work to support everyone? This is where leadership counts.