Foreword

Dr Michael J. Green

Chief Executive Officer, United States Studies Centre

With the end of the Cold War the United States, Australia, and Japan had the luxury of taking widely different approaches to democracy and development in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. The collapse of the Soviet Union and opening and reform in China seemed to remove the threat of revolution and falling dominoes. American air and naval power in maritime Asia ensured that regime change anywhere in the region did not threaten overall deterrence and stability. While the three countries adhered to the norms of the advanced industrialised democracies, they also diverged and sometimes clashed. In the early 1990s, Japan challenged the so-called “Washington consensus” at the World Bank and claimed to speak for Asian values and non-interference in domestic affairs. The US Congress moved to condition diplomatic and trade relations more on human rights without having to fear the geopolitical consequences of blowback in the region. Australia sought to straddle the Anglo-American “Washington consensus” and the imperative to be a good neighbour in Asia. There were disagreements and clashes, but geopolitics did not hang in the balance.

That has changed, of course. Xi Jinping has articulated a vision for Chinese regional hegemony built on normative leadership and a Global Civilisational Initiative meant to deny the universality of “Western” democratic norms. The Peoples’ Liberation Army Navy and Air Force are contesting US air and naval dominance in the region and coercing maritime rivals from Japan to Indonesia and India. Beijing is exploiting weak governance and rule of law in smaller states to build influence and dual-use civil-military ports and facilities on the back of “elite capture.” The stand-off between the United States and its allies on the one hand and China and Russia on the other is creating a permissive environment for egregious human rights violations in Myanmar and North Korea and democratic backsliding elsewhere. This only reinforces a dangerous spiral.

Geopolitics, democratic values, and development are intersecting with sudden velocity. And in this emerging geopolitical contest and struggle to define democracy and development strategies, Japan and Australia will remain first movers in terms of shaping approaches among other democracies, including the United States.

The United States has always had strong constituencies for advancing human rights and democracy in Congress, civil society, and the federal government itself. But President Joe Biden was the first president since George W Bush to make democracy support a national priority, going even further than Bush by framing it in terms of a clash with world autocracies. Japan began emphasising democratic norms two decades earlier when then-Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro announced in January 2002 in Singapore that democracy and human rights should be considered Asian values and would be priorities for Japan, something reaffirmed with the 2022 National Security Strategy. Yet on the ground, Japanese policies on democracy support have not shifted to reflect this new strategic framing, nor has Tokyo been entirely comfortable with the Biden administration’s more Manichean formulation. The Australian Government was equally uncomfortable with the US framing and in contrast to Japan has muted the emphasis on democratic norms as Canberra braces for an onslaught of PRC money and diplomatic overtures to the Pacific Islands. Yet Australian aid policies are probably closer to the approach taken by the United States than the policies of Japan, since Canberra has long provided support for NGOs to build civil society whereas Japan still largely looks to host governments to approve projects.

In this emerging geopolitical contest and struggle to define democracy and development strategies, Japan and Australia will remain first movers in terms of shaping approaches among other democracies, including the United States.

These differences matter. The point is not that the United States, Japan, and Australia can or should follow the same strategies for democracy and development in a contested Asia. US history, size, and system of checks and balances all produce enthusiasm and capacity for democracy support that would not come as easily for either Japan or Australia. But Japan and Australia will be the two most critical partners in this endeavour for Washington. And in terms of political system, size, and impact, Australia and Japan may have a stronger likelihood of aligning approaches with each other than either would with Washington.

For these reasons, the United States Studies Centre (USSC) at the University of Sydney is delighted to publish this collection of analytical essays on Japan’s and Australia’s respective approaches to geopolitics, Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, and the overlay of democracy on development and diplomacy towards those subregions. There are no comparable studies available, and policymakers and scholars alike will find this volume a valuable blueprint to strengthen Japan-Australia strategic cooperation on democracy and development — and by extension both countries’ influence on US strategy and ultimately the approaches of other key donor countries like Korea, Canada or the European Union. In short, Japan-Australia cooperation could be the catalyst for a more successful alignment of international approaches to democracy in a contested Indo-Pacific.

USSC Non-Resident Senior Fellow and distinguished scholar of Asian international relations Dr Lavina Lee designed this study, recruited a top-flight collection of authors, and then produced actionable recommendations from the findings. This work builds on the USSC hosting of the Sunnylands Initiative on Democracy in the Indo-Pacific in Sydney in 2023, where thought leaders from across the Indo-Pacific gathered to articulate a vision for democratic unity in a regional context. The Centre will do additional research and policy analysis in this area on the back of this excellent collection of essays. It is our hope that other institutes, scholars, policymakers and legislators will be inspired to do the same.

Introduction

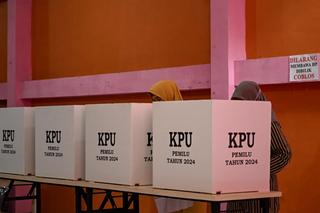

Dr Lavina Lee

In its annual report for 2023, Freedom House found that global freedom declined for the 18th consecutive year. Political rights and civil liberties diminished in 52 countries and improved in only 21, affecting one-fifth of the world’s population. Among the leading causes of democratic decline in the last year was the manipulation of elections: by incumbent governments to create an uneven playing field for opposition parties (e.g. Cambodia, Poland and Turkey), altering election results after voting has taken place (e.g. Guatemala, Thailand and Zimbabwe), military coups overthrowing civilian governments (e.g. Niger), electoral violence (e.g. Nigeria), political interference and military coercion during electoral campaigns by foreign authoritarian governments (e.g. Taiwan) and the denial of civil and political rights in disputed territories (e.g. occupied Ukraine). The Indo-Pacific is not immune to these trends with democracy coming under direct assault in Hong Kong, Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Taiwan, widespread disinformation becoming a feature of public discourse, expanding digital authoritarianism being used by governments to suppress free expression, whilst embedded corruption continues to undermine confidence in democratic systems.

Democratic decline and growing authoritarianism in the world are occurring at a time of intensifying geostrategic competition between the United States (and its allies and partners), China and Russia. This competition is viewed as a comprehensive one, encompassing technology, trade, investment, climate change, green transformation, defence and security. It goes beyond the material, however, and includes contestation over ideas — over the rules governing inter-state behaviour, the principles underpinning global institutions, standard setting for investment, trade and digital governance, as well as the internal political systems of states. China is actively courting the Global South with its alternative non-liberal vision of a “global community of shared future” through the Global Development Initiative (GDI), the Global Security Initiative (GSI), and the Global Civilisation Initiative (GCI).

Beijing directly supports other autocracies to consolidate their rule, sharing best practices and technological tools on how to surveil and suppress domestic opposition, providing aid and investment, shielding autocrats from scrutiny and condemnation in international forums, and actively promoting China’s authoritarian brand of capitalism as superior to liberal democracy. Over time, it has become more obvious that the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is more than an infrastructure investment vehicle but also a means to extend influence over regional states by means which exacerbate corruption and exploit weak democratic institutions and the rule of law. China’s “no-limits partnership” with Russia and diplomatic and economic support for the latter in its war on democratic Ukraine takes this one step further.

Japan and Australia have both adopted a broadly ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) strategy or vision, representing a values-based turn in their foreign policies. Japan, under Shinzo Abe, was the first to adopt a FOIP strategy as a response to a more aggressive China under the leadership of President Xi Jinping. They have joined with the United States in forums like the G7, NATO and the Quad to develop strategies to support the existing liberal rules-based order across the issue areas mentioned above. They have not, however, followed the United States in taking on this ideological competition beyond state borders. Japan and Australia’s FOIP strategies focus on the liberal rules-based-order as it applies to relations between states (the international rule of law, freedom of navigation and the seas, freedom from coercion and the threat/use of force) but less in terms of shaping liberal and democratic practices and institutions within states.

The report makes the case for why Japan and Australia should place greater emphasis on democracy support in their foreign policies to achieve both the objectives of their respective FOIP strategies, as well as their aid objectives of reducing poverty and creating conditions for sustainable development.

The United States has a proud tradition of promoting democratic values in its foreign policy, even if it has not been historically emphasised consistently by different administrations. USAID is the largest provider of democracy assistance in the world — defined as funding to support independent media, the rule of law, judicial reform, human rights, good governance, civil society, pluralistic political parties and free and fair elections. The US Congress actively supports democratic programs around the world through the work of the National Endowment for Democracy, the International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute. Whilst the United States has had its own struggles with democracy at home, the Biden administration openly describes the international context as one of an overarching struggle between democracy and autocracy and has set out to support democracy as a major foreign policy priority, including increased funding and efforts to demonstrate that democracy can deliver.

In contrast, Australia and Japan have traditionally been reluctant to overtly provide democracy support or assistance in their aid programs. Neither directly promotes the value of liberal democratic systems nor assists on the basis that democracy goes beyond elections and also requires the fostering of a democratic culture within society and the participation of a diverse range of stakeholders. They have been sensitive to perceptions that they might be attempting to impose Western values on their neighbours rather than respecting their sovereignty and individual choices.

However, whilst both democracies tie their hands, fearing to offend, China is using various foreign policy tools to exert greater influence in regions of strategic priority, to support authoritarian states, promote authoritarian values and provide infrastructure investment and development assistance in democratic states using means that are untransparent, non-competitive, and shielded from scrutiny within democratic nations from opposition parties, constituents, and the media. Such investment and aid have provided opportunities for elected leaders to personally or politically profit from these transactions and with such corruption degrading already weak democratic institutions and practices.

There are a large number of democracies in the two most important geographic areas of strategic interest for both Japan and Australia: Southeast Asia and the Pacific. It should be of concern to both that democratic backsliding is often associated with greater acceptance of China’s preferred interests, norms and institutions. Countering democratic backsliding should therefore be an essential pillar of the Australian and Japanese FOIP strategies.

As resident powers, Australia and Japan have to work together to complement, but not necessarily always mirror US approaches. This report explores whether and how both countries can work more effectively — separately and together — to more directly support democracy as part of their FOIP strategies. The following report:

- Investigates the similarities and differences between Australia and Japan in their approach to democracy support activities in their foreign policies;

- Identifies why those differences in approach occur;

- Explores how each country currently supports democratic principles and practices through their aid programs in Southeast Asia and the Pacific; and

- Explains how liberal democratic norms and practices are being contested in each region by authoritarian states.

The report makes the case for why Japan and Australia should place greater emphasis on democracy support in their foreign policies to achieve both the objectives of their respective FOIP strategies, as well as their aid objectives of reducing poverty and creating conditions for sustainable development, with recommendations on how they might do so.

Executive summary

Both Australia and Japan have adopted Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategies in recent years based on the assessment that Chinese policy and actions have begun to erode the foundations of the post-Second World War US-led liberal order. Both have formed deeper partnerships with each other, and other democracies — including India and the United States through the Quad — to coordinate and collaborate on policy to counter these trends in the realms of critical technology, trade, infrastructure investment, standard-setting, digital transformation, health and climate change.

Whilst recognising that the Chinese challenge is also a normative challenge to international order, both have been slow to recognise how China’s strategic messaging, infrastructure funding, aid and business practices are contributing to democratic backsliding in the Indo-Pacific. Both have been reticent to overtly use democracy support within their aid programs as a tool of statecraft to counter this phenomenon within Southeast Asian and Pacific Island countries. They are more comfortable in emphasising threats to external aspects of the global order — in terms of the threat of coercion or actual use of force, and failure to respect the international rule of law — rather than the internal erosion of liberal democratic norms within states.

Australia and Japan are reluctant to commit to an explicit policy of supporting and strengthening democracy in the region. Unlike the United States, which is an active promoter of democratic practices as part of its foreign policy, Australia and Japan are not global powers. Their geographical proximity to both Southeast Asia and the Pacific makes these two countries reluctant to emphasise the importance of supporting and strengthening democracy in their dealings with regional states for fear of attracting criticism or hostility. Intensifying geostrategic competition has led both Canberra and Tokyo to put even greater emphasis on cultivating good relations and maximising influence vis-à-vis governments in these two sub-regions, regardless of regime type.

All the while, democratic backsliding in both the Pacific and Southeast Asia is occurring and is well documented. Chinese policies, practices and narratives are not the only cause of this phenomenon but are a significant factor.

There is fertile ground for the promotion of authoritarianism in the region. In Southeast Asia, an existing problem is a relatively shallow commitment to democratic systems and liberal values. Public opinion surveys demonstrate that populations take an instrumentalist view of the virtues of democracy i.e. they judge democracy according to whether it can deliver economic development. Rather than blaming the party in power for inadequate economic outcomes, they blame the democratic system as failing. And in many cases, regular elections alone cannot overcome sub-optimal developmental outcomes resulting from poor separation of powers, inadequate checks on governmental power, limited civil society participation, restrictions on freedom of the press and corruption. This helps to account for both authoritarian resilience and democratic erosion in some countries. It provides fertile ground for Chinese messaging that its authoritarian model provides a superior alternative to democracy that is able to maintain social order and rapid economic development even if economic, social and political freedoms are restricted.

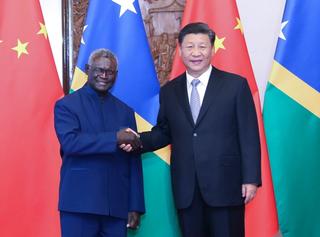

In the Pacific, but also in Southeast Asia, China is engaged in winning the favour of democratically elected leaders, known as ‘elite capture,’ by providing corrupt payments — used for personal gain, to reward patronage networks or to pay off opponents — in return for business and infrastructure contracts, access to natural resources or support for Beijing’s political and strategic objectives. These Chinese aid, investment and business practices — including via the Belt and Road Initiative — deliberately degrade or circumvent liberal norms such as transparency of government decision-making and financing arrangements, accountability of institutions and freedom of information, which may lead to a permanent erosion of democratic institutions and practices in some nations. In some cases, such as the Solomon Islands, the leadership has become even more dependent on the CCP to keep itself in power and emboldened it in delaying elections and suppressing free media.

Both Japan and Australia currently support democracy in their aid programs, but Australia does so to a significantly greater extent and includes a wider range of activities. For example, in 2021, 21 per cent of Australian aid to Southeast Asia was devoted to “governance.” In 2022, Japan directed 0.46 per cent of its total aid to Southeast Asia to “governance and civil society” whilst almost half of all aid from 2013–22 went to support economic infrastructure and services. Both countries support elections, judicial reform and legal capacity building, as well as efforts to strengthen good governance through programs which help to build the policy-making, technical and administrative capability of public officials.

Japan’s aid program has traditionally been delivered at the request of recipient governments and not directly to civil society groups. Recent changes to Japan’s 2023 Development Cooperation Charter may lead to a more proactive approach with the inclusion of “offer-type” development cooperation in collaboration with international and sub-national actors, including civil society organisations (CSO). Australia’s aid program is not similarly restricted and includes greater involvement of local civil society/NGO organisations to deliver services and programs, support for CSO voices, the promotion of gender equality, parliamentary exchanges and media training.

However, where governance-type activities are supported, the emphasis in both countries’ aid programs is on ‘state-building’ activities that improve government competence and service delivery with the intent to progress economic development and poverty reduction. It is hoped or assumed that in the longer term, this could lead to or deepen democratisation and cultures of democracy — of accountability, transparency, rule of law, and free and fair elections — as occurred post-Second World War in countries in East Asia, including Japan.

In essence, both take a passive approach to supporting democracy. In doing so, they are neglecting an important tool of statecraft that can directly counter the phenomenon of Chinese elite capture and the degradation of democratic practices and good governance that come with it. Stronger support for strengthening democratic institutions, the promotion of civic space, robust civil society participation and free media in the political process provides a direct counter to elite capture. The enabling of such alternative centres of power capable of advocating for multiple interests in society, and demanding transparency and accountability from government, indirectly shapes the political environment in which elites act and limits their political choices. Only populations in democratic countries — even those with weak institutions such as the Maldives, Sri Lanka and Malaysia — have been able to expose corruption, hold elites to account and ensure they work to the benefit of the long-term interests of their countries.

Greater support for democracy promotion within both Australia and Japan’s aid policies and programs can take place whilst being sensitive to the varying levels of commitment to democratic values in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Liberal democratic values should not be imposed on other countries in respect for their sovereignty. In any event, aid programs cannot be delivered without the consent and approval of recipient governments.

Approaches should be tailored according to the existing level of commitment to democracy in recipient states. Governments of countries that openly identify as democracies are more likely to welcome assistance from Australia and Japan to strengthen their democratic institutions and practices, and should be the focus. This could go beyond the conduct of elections and building the capacity of government officials and judiciaries to do their jobs well, to include direct support for civil society groups (including those involved in the political process), and independent media.

In illiberal or electoral democracies, wide-ranging democracy support activities beyond those that provide technical and policy capacity building for government officials and the judiciary are infeasible and are likely to undermine good bilateral relations. Both Japan and Australia undertake these activities currently and should continue to do so to generate goodwill and achieve long-term economic, social, and humanitarian outcomes. Under the principle of doing no harm, both countries should, however, be mindful that “good governance” activities in these countries might be merely enabling autocratic governments to become more competent, shielding them from bottom-up demands for greater freedoms.

Providing greater aid and concessional loans for infrastructure investment by Japan and Australia in Southeast Asia and the Pacific also indirectly safeguards democratic institutions and practices. They do so by offering an alternative to Chinese investment based on standards that promote open tendering, public transparency of contract terms, adherence to minimum labour standards, assessment of national benefits, and the consideration of environmental and social impacts. Telecommunications infrastructure and submarine cables should be an important area of aid and investment to safeguard data privacy and disruption by authoritarian actors.

Japan continues to lead the provision of ODA in Southeast Asia, whilst Australia leads in the Pacific. There is a significant opportunity to expand the scope of their individual and joint efforts in supporting projects improving connectivity, climate mitigation and adaptation, telecommunications and undersea cables, and digital transformation.

Recommendations

Joint recommendations for Australia and Japan

- Both Australia and Japan should place greater emphasis on democracy support activities within their aid policies to further the poverty reduction and developmental objectives of these policies as well as their strategic objective of supporting a free, open and prosperous Indo-Pacific. Both governments should recognise that development assistance is being used by China in ways that undermine democratic institutions and circumvent government transparency and accountability whilst simultaneously undercutting their strategic influence in both Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

- Japan and Australia should work together to jointly support infrastructure investment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific based on Japan’s ‘quality infrastructure principles’ (adopted by G20 countries in 2019) to provide an alternative to Chinese-led ODA and loans which are delivered by means that degrade democratic institutions and practices in recipient countries.

- Strategic messaging is an essential tool of statecraft. Both Australia and Japan should engage in whole-of-government efforts to challenge Chinese narratives about the superiority of authoritarian systems to liberal democracies in the achievement of economic development and social order. The current reticence of both countries to openly explain the benefits of liberal and democratic institutions offers China uncontested space to promote its own authoritarian capitalist model as superior, without proper scrutiny of this claim.

- Australia and Japan need democratic Southeast Asian partners. Indonesia is a prime candidate. It is the largest Muslim-majority democracy in the world and is proud of its tradition of South-South Cooperation (SSC) since the Bandung Conference of 1955 and internal consolidation of democracy since 1998. It is eager to share its experience of democratisation with developing countries in the form of SSC. Australia and Japan should work with Indonesian organisations and experts to explore principles and pathways to democratisation that are most suitable for Southeast Asian nations. This could utilise mechanisms such as the Bali Democracy Forum or the creation of new ones.

- Australia and Japan should enhance coordination of democracy support activities with other like-minded democracies that provide aid for this purpose such as the United States, South Korea, the European Union, individual European countries and emerging donors such as India and Indonesia. This would improve the efficiency and effectiveness of democracy support programs and avoid duplication of effort.

- Australia and Japan should play a greater role in providing a safe haven for young pro-democracy activists from Myanmar, Thailand, China, Hong Kong and elsewhere who have been forced to flee political persecution. Japan has a history of harbouring many Asian exiles, dissidents, and intellectuals who resisted colonial and dynastic rule, such as Sun Yat-sen (father of the Republic of China), Song Jiaoren (first leader of the Chinese Kuomintang), and Phan Boi Chau (leader of the Vietnamese independent movement). As such history teaches, current exiles may become future leaders of their country. Australia too has a history of supporting democracy activists in exile (e.g. East Timor and most recently Hong Kong) but could expand its activities.

- Japan currently does not have a significant number of civil society organisations both willing and capable of supporting democratisation programs as part of ODA. Both Australia and Japan could work together to support capacity building for Japanese CSOs working in democracy support, the promotion of human rights and free media by creating a platform by which Japanese CSOs can build networks and regularly engage with other CSOs in the Indo-Pacific. This idea has already been developed by Yukio Takasu, former Japanese Ambassador to the United Nations, who has proposed the creation of an Indo-Pacific Platform for Universal Values to serve this role. It is worthy of support by both governments.

- At the government-to-government level, both countries should provide greater support for more exchanges between Japanese and Australian parliamentarians and their counterparts in the region in order to expand understanding of — and exposure to — varieties of democratic parliamentary and legislative norms and practices.

Recommendations for Japan

- Japanese ODA directed towards democracy support activities is too low and has been in decline in recent years. Japan has both moral (poverty reduction and economic development) and strategic imperatives to support democracy more substantially in its ODA program as a direct counter to the degradation of democratic practices in regions of strategic priority i.e. Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Japan currently supports capacity building for government officials, elections, and support for judicial training and legislative reform. These activities should continue and be expanded substantially.

- Japan should be less reticent to offer democracy support programs in countries that identify as democracies with existing societal expectations of universal suffrage, relatively free and fair elections, independent media and civil society participation. Assisting these countries more robustly with elections, technical capacity building, judicial reform, and legislative, media, civil society and parliamentary capacity building will likely be welcomed and not viewed as the imposition of Western values.

- Japanese ODA for the provision of infrastructure should continue but should also be framed in terms of providing indirect support for democratic and accountable governance practices in the Indo-Pacific. The selection of projects should have democracy support in mind to further Japan’s strategic objective of supporting a free and open Indo-Pacific. For example, Japan’s 2023 decision to join with Australia and the United States to build an undersea cable between Micronesia, Nauru and Kiribati supports economic development in these countries, whilst also ensuring that critical infrastructure is operated under democratic principles.

- Now that the 2023 Development Cooperation Charter opens the possibility for “offer-based” ODA programs, Japan should consider going beyond supporting initiatives focused on climate change/green transformation, economic sustainability and digital transformation to also support initiatives to expand the number and build the capacity of Japanese CSOs to deliver democracy support programs within the region.

Recommendations for Australia

- The Australian Government needs to formally accept that development assistance is being used by countries such as China to change governance institutions and norms in recipient countries. In addition to maintaining high ethical and technical standards, Australian development assistance also needs to be deployed to influence elite behaviour, develop transparent and accountable governance institutions, and expand civil society and free media participation in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Strategies and specific projects should be selected and designed to include this geopolitical and normative purpose.

- Australia already currently provides significant support for the development of good governance practices in the Pacific and Southeast Asia. This is mostly directed towards ‘state-building’ efforts i.e. building the capacity of government officials to improve technical and policymaking capabilities and improved service delivery to achieve economic development. These are worthy programs. However, greater support for the development of democratic practices and a culture of transparency and accountability in society should be prioritised within the aid program to counter opportunities for elite capture and prevent the degradation of democratic institutions and practices. Australia should increase the weighting of aid for support to local CSOs with a view to building their capacity to advocate for their constituencies and enter the political process.

- Australia should provide greater ODA to directly support training for journalists and the operation of independent media organisations in the Pacific. Currently, Chinese state media companies have begun to operate in the Pacific, and there is evidence of Chinese influence over independent media companies being achieved with small outlays. Direct support for independent media would counter these activities and ensure it can play a role in providing factual reporting and holding decision-makers to account.

- Australia should significantly expand support for the training of journalists in both the Pacific and Southeast Asia as a key means of supporting democracy at a time when misinformation and disinformation through social media platforms have become commonplace. This could involve the expansion of supported traineeships and internships in Australia.

- The Australian Government and related entities should provide support for non-governmental entities and experts to explore the causal importance and impacts on economic development of bottom-up liberal institutions and practices and to directly interrogate assumptions about authoritarian competence applied to Southeast Asia and developing economies in general. While these conversations led by independent entities and experts will not always align with Australian Government messaging, entering and occupying ground currently dominated by those championing authoritarian competence is a step in the right direction.

Democracy support in Australian foreign policy

Dr Lavina Lee

Traditionally, Australia has not followed the United States in the overt promotion of democracy in its foreign policy. Even so, historically liberal values have influenced Australia’s preference for multilateralism, support for global institutions and the allies and partners it has chosen to pursue its national interests. In this sense, Australia’s foreign policy identity is based on its own domestic commitment to liberal democracy and a global order based on liberal internationalist principles. Since 2017, Australia has implicitly embraced a version of Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy designed to counter Chinese policy and actions that have begun to erode the foundations of the post-Second World War US-led liberal order. It has done so in partnership with the United States, Japan and India, the three most capable and forward-leaning Indo-Pacific democracies, via the Quad and other bilateral and trilateral arrangements. Australia recognises that China represents an economic, technological, military/strategic, institutional and normative challenge to the liberal global order. Yet, supporting democratic values and practices through foreign policy instruments such as development aid, has not played a major role in Canberra’s FOIP strategy. There is still a reticence to pierce the veil of sovereignty to support what might be regarded as ‘Western values’ even as Chinese practices are eroding already weak or fragile regional democracies. This chapter discusses the historical role of liberal democratic values in Australian foreign policy, the values-based turn in Australia’s current FOIP strategy, and the current role of democracy support in Australia’s development assistance policy. It then makes the case for greater emphasis on democracy support activities as an underappreciated means to counter authoritarian trends in Australia’s neighbourhood.

Democracy and liberal values in Australian foreign policy

Liberal values have always underpinned Australian foreign policy, even if its leaders have not always emphasised them as guiding principles. The two enduring traditions in Australian foreign policy — dependence on an alliance with a non-resident great-power and ‘middle-power’ activism — are both strongly influenced by Australia’s liberal identity. Australia’s two alliance partners since federation in 1901 — Britain until the fall of Singapore in 1942 and since then, the United States — share similar characteristics. This goes beyond a common Anglo-Saxon heritage and includes the capacity to maintain open sea lines of communication and balance against or suppress any expansionist tendencies of a rising great power in the Far East.1 The strength of these alliances draws from the shared commitment to liberal democratic values, institutions and practices and an aversion to authoritarian political systems.

Australian foreign policy has also been characterised as ‘middle-power diplomacy’ or ‘activism.’2 Australia has been a strong supporter of global institutions based on liberal internationalist principles. This includes the United Nations since its inception, the Bretton Woods institutions, human rights treaties, nuclear non-proliferation, the World Trade Organization, and the rule of law through adherence to treaties like UNCLOS and the ICJ. Middle power diplomacy was most strongly associated with Gareth Evans, Australia’s foreign minister from 1988 to 1996. Evans’ brand of middle power diplomacy is associated with “coalition building with ‘like-minded’ countries” within existing multilateral institutions, but also building new institutions to pursue liberal internationalist interests and values such as trade liberalisation, WMD non-proliferation and post-conflict diplomacy.3 It involves notions of being a ‘good international citizen’ through the provision of humanitarian aid which, in Evans’ words, Australia’s “democratic community expects its government to pursue” to create “just and tolerant societies.”4 The subsequent Howard government in turn espoused a liberal formula for state-building based on “security and the rule of law; transparent and efficient bureaucratic institutions; the provision of essential services to the population; the operation of democratic processes and norms; and the fostering of conditions for market-led development.”5

Nevertheless, Australian governments have remained wary of too overtly promoting or supporting democracy in the Asia-Pacific region even as the third wave of democratisation washed over Southeast and East Asia at the end of the Cold War. This is attributed to strong push-back in parts of the region against the idea that liberal democratic values are universal, rather than a Western construct incompatible with distinct Asian values.6 In the late 1980s and 1990s prominent Southeast Asian prime ministers Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore and Mahathir Mohamad of Malaysia argued that successful Asian economic development rested on the privileging of communal interests rather than individual rights, order over personal freedom, respect for political leaders, a culture of hard work and thrift and an intertwining of government and business.7 It was Mahathir who for years thwarted Australia’s attempts to join ASEAN-led institutions such as the East Asian Summit and its predecessors on the grounds of identity, famously saying “[Australians] are Europeans, they cannot be Asians.”8 Pragmatically, the Howard government downplayed this perceived difference in values and identity as the price of entry to Asian regional institutions.9 The promotion of liberal values had become an impediment to Australia’s acceptance among Asian countries as belonging to and having a legitimate stake in the region. The Howard government also distanced itself from ‘middle-power’ diplomacy as a concept as one too closely associated with Labor. In circumstances where US foreign policy itself preferred unilateral approaches to multilateral ones, ultimately the Howard government chose the US alliance over middle-power diplomacy, supporting the United States in both Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003. Nevertheless, in its framing of the greatest threat to Australian security — Islamic terrorism — the Howard government too saw these challenges as ideological, threatening liberal freedoms within the state.

With the rise of China however, there has been a distinct and more obvious values-based turn in Australian foreign policy noticeable first in the 2016 Defence White Paper and its emphasis on defending a ‘rules-based order’ and then more prominently in the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper. The latter is upfront about liberal values being the foundation of Australian foreign policy, stating: “Our support for political, economic and religious freedoms, liberal democracy, the rule of law, racial and gender equality and mutual respect reflect who we are and how we approach the world.”10 A recurring theme is the contestation and erosion of the prevailing US-led liberal order as being contested by actions which implicated China, with allusions made to states that “are active in asserting authoritarian models in opposition to open, democratic governance,”11 and the increased use of “measures short of war” to pursue political and security objectives.12 To safeguard the ‘rules-based order’ the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper commits Australia to “work more closely with the region’s democracies” to support a “balance in the Indo-Pacific favourable to our interests and promote an open, inclusive rules-based region.”13

The return of liberal values expressed in both documents reflects changing threat assessments in response to increasing Chinese aggression and ambition under the leadership of Xi Jinping from 2012 onward. This included its expanding territorial claims and aggressive actions toward rival claimant states to exert de facto control over vast swathes of international waters and disputed features of the South and East China Seas. Added to this was Beijing’s refusal to abide by the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling invalidating its nine-dash line claim in the South China Sea and growing apprehension about the scale, ambition and strategic consequences of the Belt and Road Initiative (i.e. the emergence of ‘debt-trap’ diplomacy). It was also during this period that the federal government began investigating the extent of foreign interference within Australia, including the activities of United Front organisations, as well as the security implications of Chinese investment (by both Chinese state-owned enterprises and private firms) in critical infrastructure. No doubt, Australian policy approaches were also influenced by the Abe administration as the first official creator and promoter of the ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ concept in 2016.

Whilst AUKUS is focused on developing cutting-edge military capabilities to deter adversaries from using force to realise expansive territorial ambitions, the broad agenda of the Quad is about demonstrating that democracies can deliver on the greatest challenges of our time and join in defence of liberal norms.

Australia’s embrace of the Quad — as a grouping of the four most formidable democratic countries in the Indo-Pacific joined together in pursuit of a “free, open and inclusive” regional order — is the direct manifestation of this. Another is the creation of the AUKUS partnership which joins Australia with its historical allies to create a potent technological and military-industrial partnership. Both entities are viewed as essential to a collective democratic pushback and reassertion of democratic power, relevance, and strategic agency. Whilst AUKUS is focused on developing cutting-edge military capabilities to deter adversaries from using force to realise expansive territorial ambitions, the broad agenda of the Quad — covering vaccine delivery, infrastructure and digital standard-setting, maritime domain awareness, and green technology — is about demonstrating that democracies can deliver on the greatest challenges of our time and join in defence of liberal norms.

These activities have taken on a higher level of urgency with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the emergence of the China-Russia ‘no-limits’ partnership, which then-Prime Minister Scott Morrison described as a “new arc of autocracy” that is “instinctively aligning to challenge and reset the world order in their own image.”14 The Albanese government has dampened rhetoric on the deepening competition between autocracies and democracies, returning to an emphasis on the external aspects of a ‘rules-based’ order that are still under threat by authoritarian practices, but which appeal to small and middle-powers regardless of their political system i.e. respect for the rule of law and right of states to exercise sovereignty without the threat or the use of force those stronger than them.15

Yet Canberra clearly recognises that strategic competition between democracies and autocracies is intensifying at all levels, that a Russian victory in Ukraine has direct implications for Chinese ambitions to unify with Taiwan by force, and that the deepening influence of Beijing in Southeast Asia and the Pacific is occurring at the expense of Australian interests. It continues to forge ahead with Quad-based initiatives, as well as deepening bilateral and trilateral cooperation with the same Quad partners. The latest “strategic direction statement” of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) from May 2023 states for example that:

Australia now faces the most challenging strategic circumstances of the post-war period, circumstances with require unprecedented coordination and ambition in our statecraft. Our region — the Indo-Pacific — is being reshaped amid rapid strategic and economic change, with increasing risk of miscalculation or conflict. Australia’s objective is to contribute to a regional balance of power that bolsters peace and stability, by shaping an open, stable and prosperous Indo-Pacific. To achieve that, Australia must harness all elements of national power.16

That is, the pace and scale of increasing Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific requires a whole of government response, that utilises multiple tools of statecraft. This includes for example investment in diplomacy and strategic messaging, building military capability, cooperation with allies on intelligence sharing, joint development of high technology, coordination of policy with allies on semiconductors, AI, climate technologies, trade, investment and export policies, and promotion of standards supportive of liberal values covering 5G and ‘quality infrastructure’ etc. Even so, there has not been a clear articulation of the role, if any, that democracy support — i.e. the use of foreign policy tools to assist or encourage liberal democratic governance in other states — should have as a tool of Australian statecraft or as part of a push-back agenda with like-minded democratic partners.

Australia’s response to Chinese strategic competition: Tools of statecraft in the Pacific and Southeast Asia

Australia’s primary areas of geo-strategic interest within the Indo-Pacific are the Pacific Islands and Southeast Asia. The Second World War demonstrated the strategic importance of the Pacific to Australian security. Since then, it has worked to maintain a position of pre-eminence as the preferred development and security partner of most Pacific Island nations (excluding French Polynesia; the US Compact of Free Association states; and the Cook Islands and Niue which receive most aid from New Zealand). It is a member of the Pacific Islands Forum, and between 2008–21 was the largest development partner of the region accounting for almost 40 per cent of the total ODF of around US$17 billion in disbursed funds. It is also the largest provider of grant funding, with around 95 per cent of Australian funding coming in this form.17 Over the same period the next closest providers of official development finance have provided less than US$5 billion each and in descending order are the Asian Development Bank, China (US$3.9 billion disbursed), Japan, New Zealand, the United States, the World Bank and the European Union.18

On taking office in May 2022, the Labor government received an immediate wake-up call on Chinese ambitions in the Pacific, including the establishment of a foothold for the PLAN. In April 2022, the Solomon Islands signed a security agreement with China, marking the first agreement of its type between a Pacific Islands nation and Beijing. The agreement itself was not made public, but a leaked draft provided for the deployment of Chinese “police, armed police, military personnel and other law enforcement forces” to the Solomons to “assist in maintaining social order” and for PLAN warships to gain access to ports for stop-overs and replenishment.19 This opened the door to a greater Chinese military presence less than 2000 km from the northeast of Australia.20 Ahead of the May 2022 federal election, the then Labor opposition accused their government opponents of severely neglecting Australia’s diplomatic relationships in the Pacific, describing the pact as the “worst foreign policy blunder in the Pacific since the end of World War II.”21 Worse still was the Chinese proposal put to the second China-Pacific Foreign Ministers meeting in May 2022 for a comprehensive China-Pacific Islands economic and security agreement. This would cover trade, finance and investment, tourism, public health, Chinese language and cultural exchanges, training and scholarships, and a significant expansion in Chinese training of Pacific police forces, along the lines of the Solomons agreement. Whilst the deal was rejected by Pacific Island nations — many of whom sought to protect the Pacific from heated geopolitical competition — it made clear China’s ambition to further increase its economic and security sector influence in a region where it already dominates resource extraction industries.22 The risk of a Chinese security presence in the Pacific for Australia has not passed, with reports that China pursued PLAN access to ports in Vanuatu and PNG in 2018, and Kiribati in 2021. Its diplomatic influence within the Pacific Islands Forum continues to grow after persuading the Solomons and Kiribati to switch diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China in 2019 and Nauru to do the same in January 2023 just after Taiwan’s national election.

The Albanese government has put considerable energy and resources into arresting its declining influence in the Pacific using multiple tools of statecraft. To signal the renewed priority given to Australia’s ‘Pacific family’ within the first year of taking office, government ministers have visited every Pacific Islands Forum member, including multiple visits by the Foreign Minister Penny Wong, Minister for International Development and the Pacific Pat Conroy, and the Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese.23 The message delivered during these visits was that Australia was listening to Pacific priorities — including action on climate change adaptation and mitigation — whilst seeking to maintain its status as the Pacific’s ‘partner of choice’ and ‘principal security partner.’

The Albanese government has put considerable energy and resources into arresting its declining influence in the Pacific using multiple tools of statecraft.

In May 2023, the government announced a comprehensive package titled ‘Enhancing Pacific Engagement’ allocating A$1.9 billion over four years which mixes multiple elements of statecraft to meet Pacific needs: from aid and development, infrastructure, defence and security. This includes an estimated A$1.27 billion to develop Pacific Island nations’ security infrastructure and maritime security capability (e.g. maritime surveillance capacity to protect the Pacific’s large EEZs, providing patrol boats, and infrastructure upgrades) as well as cooperation on law enforcement involving the Australian Federal Police. Another component is A$370 million for an expansion of the Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme which allows Australian businesses to hire workers from nine Pacific Island countries and Timor Leste in sectors of workforce shortage, further enmeshing the economies of the Pacific with that of Australia. A further A$114 million is provided over four years to support the development of regional architecture primarily via the Pacific Islands Forum to assist in humanitarian relief, disaster preparedness, diplomatic capability, and security priorities with climate change foremost, followed by natural disasters, gender-based violence, illegal unreported and unregulated fishing, cybercrime and transnational organised crime.24 Outside of this program, in an effort to offer an alternative to Chinese infrastructure funds, in 2022 the government doubled the lending pool of the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP) from A$1.5 billion to A$3 billion. This facility is focused on supporting ‘high-quality, sustainable infrastructure,’ and had at that time finalised financing of over A$700 million for investment in airports, ports, submarine cables and solar farms.25 Finally, in 2023–24 ODA funding for Pacific countries stood at A$1.43 billion, representing around 30 per cent of the total aid budget with the top four recipients being Papua New Guinea (A$616 million), Solomon Islands (A$171 million), Fiji (A$88 million) and Vanuatu (A$85 million).26

Southeast Asia is Australia’s second most important region of strategic interest and another sphere where Chinese influence has grown exponentially. The current Albanese government has elevated the significance of Southeast Asia in Australia’s foreign policy. In 2023–24 it boosted spending on enhancing Australian diplomatic capability by A$55.7 million over four years to facilitate increased diplomatic visits and business engagement to the region.27 Southeast Asia receives the second highest proportion of Australia’s aid funding after the Pacific and has done so for many years, with A$775 million allocated in 2023-24.28 Australia has worked hard to become more enmeshed in the economic and security architecture of the region (particularly as a comprehensive strategic partner of ASEAN and a member of the East Asian Summit), pays due deference to ASEAN centrality, and has developed deeper defence, security and economic ties with Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines. Indonesia is Australia’s highest Southeast Asian aid recipient in 2023–24 at A$324 million, followed by Myanmar (A$121 million), Vietnam (A$95 million) and the Philippines (A$90 million).29 Given the greater size and complexity of Southeast Asia than the Pacific and the lower level of aid dependence there overall, Australia alone cannot decisively tilt the regional balance in material or normative terms without closer cooperation with its allies and partners.

How Australia’s aid program can help in the fight against elite capture

The Albanese government took office with the intent to increase the role of ODA as a tool of Australian statecraft, boosting ODA to A$4.77 billion in 2023–2430 from A$4.55 billion the previous year31 and committing to increase the budget by 2.5 per cent per year on an ongoing basis from 2026–27.32 Australia adheres to the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) aid standards and delivers aid directly to recipient governments, through multinational organisations, in cooperation with other countries (like New Zealand) and working directly with Australian, local and international NGOs.33 In August 2023, the government released a new International Development Policy (AIDP) — replacing the previous policy released in 2014 — in response to the “the most challenging strategic circumstances in the post-war period.”34 According to the AIDP, the objective of Australia’s program “is to advance an Indo-Pacific that is peaceful, stable, and prosperous… To achieve this requires sustainable development and lifting people out of poverty.”35 In other words, sustainable development and poverty alleviation are the route to a peaceful, stable and prosperous Indo-Pacific.

Whilst the AIDP does not mention Australia’s fears of a Chinese military presence in the Pacific, the subtext is that somehow aid can be used to arrest the decline in Australia’s regional influence. Yet, as mentioned above, Australia is already by far the largest aid provider to the Pacific Islands providing 40 per cent of all aid since 2008 and has already generated considerable goodwill among Pacific Islander peoples from its generosity, particularly by providing direct budget support during the COVID pandemic. In contrast, China’s expanding clout in the Pacific has come about via a much lower level of ODF, at around nine per cent over the same period.36 After a peak in development financing in 2016, China’s loan disbursements fell to US$241 million in 2021, below the pre-pandemic average of US$285 million since 2021.37 China has managed to achieve more of its strategic objectives, with a lot less.

Elite capture

How then, has Beijing been able to create this outsized level of influence at Australia’s expense? It has done so by using a strategy of elite capture i.e. directly targeting the personal and political interests of a small number of Pacific elites in positions of power. China has shifted from a “loud and brash” to a “small and beautiful” and “politically targeted” approach to ODF directly rewarding those politicians and countries that officially recognise the PRC rather than Taiwan.38 In the Solomon Islands, China has financed the US$53 million 2023 Pacific Games stadium and other sports facilities, as well as committing loan funds to build 161 mobile communication towers supplied by Huawei.39 There are also numerous reported instances of Chinese aid being used to make direct and indirect payments to governing elites in return for business contracts, access to natural resources or support for Beijing’s political preferences. In 2018, a large-scale example was the use of Chinese aid to make a A$1 million bribe to Sir Michael Somare, the former prime minister of PNG.According to PNG authorities and Singaporean anti-corruption investigators, these funds came from a A$4.7 million slush fund established by Chinese phone company ZTE in 2010 to ensure it was awarded a contract in PNG.40 Prior to the signing of the Solomons-China security pact in 2022, credible media reports suggested that Prime Minister Sogavare used a Chinese-supplied slush fund to pay A$44,000 each to a number of MPs to avert a likely no-confidence vote in parliament. This vote of no-confidence arose after violent riots in the capital by protesters dissatisfied with his government and its decision to switch recognition from Taiwan to China.41 China’s use of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) funding to exploit and exacerbate ongoing corruption and existing institutional weaknesses in democratic states has been documented in the Maldives,42 Sri Lanka with the now infamous ‘debt trap’ diplomacy associated with Hambantota Port in 2017,43 and Malaysia’s 1MDB corruption scandal that led to the fall of the Razak government.44

The decline in Australian influence in the Pacific has come about largely through Chinese elite capture and the subversion of democratic processes. Beijing is actively using economic resources to achieve its interests in ways that open up opportunities for corruption and subvert accountability processes, allowing ruling regimes to make decisions contrary to the will and long-term national interest of their citizens. Pacific Islanders are very unlikely to welcome a Chinese military presence and the heightened geo-strategic tension this would entail. Expending ever larger amounts of Australian aid in the Pacific, however, does not address these causes of democratic backsliding, and the erosion of the very good governance practices that are needed to achieve sustainable development and poverty alleviation that are the core goals of the Australian Aid program.

Democracy support can provide a direct counter to these trends by undermining the mechanisms by which China extends its influence over regional states. For example, only countries with liberal democratic institutions in place have been able to resist the worst aspects of Chinese lending through the BRI and to ensure that they operate under terms beneficial for the long-term interests of a country. In the absence of liberal democratic institutions that impose accountability and transparency in decision-making, projects can be fast-tracked without transparency, open competition for tenders, adherence to labour and environmental standards, or scrutiny of the overall national benefit. Without such transparency and open competition, BRI projects present opportunities for corruption among government elites. The ouster of Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Razak and the United Malays National Organisation from power in 2018 occurred because of the exposure of massive personal corruption, as well as the perception that he had sold out Malaysia’s interest to a foreign government for personal gain. Even Malaysia’s weak democratic institutions were able to push back against Chinese influence.

Australia and other democracies like Japan cannot enter the game of elite capture by providing direct personal or political benefits to elites to achieve strategic objectives. To do so would be unacceptable to their own publics, betray their liberal values, and undermine the long-term objective of aid policy of building effective and accountable states that will one day no longer need assistance. Development aid initiatives can, however, have an indirect influence on elite decision-making by shaping the political environment in which they act. This can occur by enabling alternative centres of political power with interests, values and goals that are aligned with ideas associated with democracy and good governance — transparency and accountability in political decision-making — that constrain the menu of political choices from which elites are able to choose. They can support the development of stronger institutions based on a separation of powers and the rule of law. Empowering civil society and the media to advocate for various community interests, and to demand transparency and accountability from governments plays an essential role in countering elite capture.

Democracy support and Australian aid policy and programming

Yet, there is no mention of democracy support in Australia’s aid policy. This absence may be explained by the desire not to “impose values on others,” as expressed in the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper.45

Some aspects of liberal governance are mentioned such as supporting partners to “build effective, accountable states that drive their own development,” new commitments to “support local leadership and local actors” through a new Civil Society Partnerships Fund,46 and the introduction of mandated targets for the inclusion of gender equality in development programs.47 The significant emphasis on women’s empowerment is an important component in building strong democratic norms, as is the participation of civil society. However, when looking at the details of what building “effective and accountable states” might look like, there is no mention of the word “democratic” to describe those states. The primary objective here appears to be effectiveness in terms of government capacity and service delivery to alleviate poverty and inequality. This is implied by the emphasis on “improving essential services,” efforts to “strengthen social protection systems,” support for “reform, service delivery and system strengthening,” and “structural reforms” that “can improve economic performance.”48

The closest one gets to supporting aspects of liberal democracy is the commitment to “respect and promote civic space, recognising the distinct nature and value of civil society in each country,” but without explaining why civil society participation in the political process might be connected to effective, transparent and accountable governance. There is one mention of “transparent, accessible and responsive governance” as benefiting effective states and citizens, which mixes cause and effect i.e. it is the principle of transparency that is essential to building effective and responsive governance. It is also unclear how much money will be allocated to the Civil Society Partnerships Fund, what kind of work it will do and whether democracy support will form part of its objectives. In her pitch to improve Australia’s standing in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s emphasis on “listening” to regional priorities, and pledge that Australia’s partnership will not come with “strings attached,” sends mixed signals about just how important building transparent and accountable governance is to Australia within its aid program.49 The overall impression is of a government reluctant to use the word democracy or explain the virtues of a liberal democratic model of governance.

In terms of spending, Australia’s aid budget devotes a significant portion to the sector “governance” which refers to “investments supporting the stronger operation of the public sector and civil society.”50 In 2021–22, this represented 25 per cent (A$425 million) of its aid to the Pacific, and 21 per cent (A$241 million) to Southeast Asia.51 Within these large figures, it is difficult to assess exactly how much funding is allocated towards democracy support i.e. to directly supporting free and fair elections, building robust democratic institutions, transparency and accountability in government decision-making, participation by civil society actors and the media in the political process including by demanding transparency and accountability from governments. “Governance” as a category is defined very broadly to include “public sector policy and management, public financial management, domestic revenue mobilisation, legal and judicial development, elections, media and free flow of information, human rights, ending violence against women and girls, social protection, employment creation, and housing policy, culture and recreation,” only some of which can properly be described as democracy support.

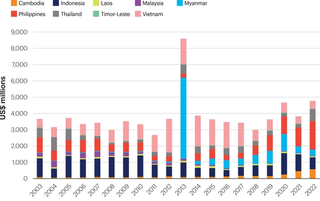

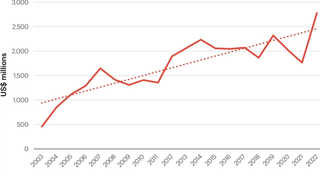

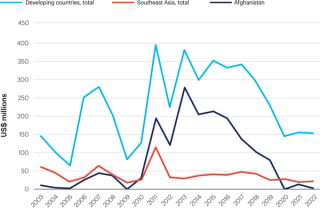

Figure 1. Australian official development assistance, region of benefit by sector group, 2021-2022

Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2022. Australia’s Official Development Assistance: Statistical Summary 2021-22. Commonwealth of Australia. p. 23.

In a 2023 submission to the parliamentary inquiry into “supporting democracy in our region,” it becomes apparent that what DFAT considers programs that support democracy includes many examples that are more accurately described as capacity building for service delivery and technical support for bureaucracies and other arms of government.52 Examples include capacity building in public financial management, state-owned enterprise reform, tax administration in Laos (under the Mekong-Australia partnership), A$178 million from 2015–22 for a poverty reduction program in Indonesia (KOMPAK), A$87 million over five years to assist Cambodia’s policy reform agenda in agriculture, trade, enterprise development and infrastructure, A$11 million from 2015–23 for support for social protection reform in the Philippines, and A$45 million over eight years for a governance and economic growth program in Samoa (Governance for Economic Growth Program — ‘Tautai’). Other programs include capacity building for courts and judiciaries, such as A$44 million over 2003–22 to the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, technical training on victim-sensitivity for judges in Laos, and cyber-crime and anti-corruption training to Kiribati officials and police.

In the absence of a clear democracy support policy, only a very small percentage of a very large pool of funds for ‘governance’ is actually directed towards building transparency and accountability of governments, civil society political participation, and a robust independent media capable of holding governments to account.

When it comes to traditional democracy support activities, support for elections is strong, including programs in Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Fiji, Nauru, PNG, Marshall Islands, Solomon Islands, Tonga, and Vanuatu. Australia does provide a region-wide training program for journalists and media organisations in the Pacific, but there are none for Southeast Asia. And whilst Australia’s aid programs are largely delivered through Australian and local NGOs (a quarter of Australia’s 2000 local partners were civil society organisations in 2021-22) it is unclear how many are delivering humanitarian programs in education and health, and how many are given support to become stronger advocates for particular constituencies or to hold governments to account. In other words, in the absence of a clear democracy support policy, only a very small percentage of a very large pool of funds for ‘governance’ is actually directed towards building transparency and accountability of governments, civil society political participation, and a robust independent media capable of holding governments to account.

Conclusion

Liberal values have historically underpinned the enduring traditions in Australian foreign policy, dependence on an alliance with a liberal-democratic non-resident great power and middle power activism. Australia has long been an active supporter of liberal international institutions, multilateralism and the idea of a global rule of law. Nevertheless, Australia has also been historically wary of overtly promoting or supporting democracy which may be interpreted as imposing Western values on others, as well as feeding perceptions that Australia and its values were separate and incompatible with those of cultures in its neighbourhood. However, over the last ten years, a distinct values-based turn can be observed in Australian foreign policy, with Canberra assessing that the US-led liberal international order that it has prospered under is being contested and eroded as China has gained power and expanded its ambitions. Australia has turned once again to liberal democratic allies and partners foremost to coordinate policy and counter authoritarian trends via AUKUS, the Quad, the G7 and on an ad hoc basis in various issue areas. The current Albanese government has emphasised external aspects of a Westphalian order that are not only supported by liberal democratic states i.e. respect for sovereignty and international law. It still, however, recognises that Australia is facing the most serious deterioration in its strategic circumstances since the Second World War. China’s authoritarian challenge is not just to the external aspects of international order, but also to liberal democratic practices within Indo-Pacific states. Chinese tools of statecraft, particularly in trade and investment vehicles such as the BRI, directly exploit and exacerbate weak democratic institutions, providing opportunities for corruption to capture elites. In doing so, this further erodes liberal institutions and commitment to democratic principles and practices in the region, with potentially lasting consequences.

Yet, Australia continues to shy away from supporting liberal democratic principles overtly in its aid policy and instead focuses on capacity building, service delivery and economic development on the assumption that cultures of democracy — of accountability, transparency, rule of law, free and fair elections — will necessarily follow. Whilst Australia is the largest aid provider in the Pacific, far greater than China, it has lost relative strategic influence because of Beijing’s strategy of providing direct personal or political benefits to elites. The missing link in countering the phenomenon of elite capture is a greater emphasis on democracy support within aid policy. Stronger support for strengthening democratic institutions, the promotion of civic space, robust civil society participation and media in the political process provides a direct counter to elite capture. Democracy support initiatives indirectly shape the political environment that elites act within, enabling alternative centres of power capable of advocating for multiple interests in society, demanding transparency and accountability from government and thereby constraining the menu of political choices elites are able to choose from. In the past, the consequences of taking a softer — even avoidant approach — to supporting democratic practices had less immediate effects on Australia’s national interest. It was a moral issue that Australian aid appeared to be merely alleviating poverty from year to year and propping up struggling governments that made slow progress moving up the development chain. Now the consequences of avoiding support for democratic practices directly impacts Australia’s influence in our neighbourhood and undermines the very aims of our aid policy i.e. achieving sustainable development and poverty reduction by building effective and accountable states in our neighbourhood. With these conclusions in mind, two recommendations are offered.

Recommendation 1

Australian aid policy should more clearly reflect a commitment to supporting democratic principles and practices in its aid programs — transparency and accountability of government, civil society participation and free media — as essential to achieving the objectives of sustainable development and poverty reduction.

Recommendation 2

Australia should provide stronger support for strengthening democratic institutions, the promotion of civic space, robust civil society participation and independent media in its aid programming.

Australian democracy support in Southeast Asia

Dr John Lee

Introduction

Southeast Asia is commonly referred to as a central battleground or swing region when it comes to the geopolitical competition between the United States and its allies on the one hand, and China and its authoritarian network on the other.53 Along with the South Pacific, Southeast Asia is identified as Australia’s primary sub-region of strategic interest.54 The Australian core interest derives from the permanence of geography. It is also increasingly driven by intensifying Chinese activities in Southeast Asia which span from the economic and military to institutional and normative. The Chinese material and non-material interests and activities in this sub-region are deepening the concern for Australia and its other democratic allies and partners. Even so, promoting liberal and democratic institutions, practices, and norms seems to be underdone when it comes to Australian statecraft.

This chapter looks at the Australian mindset and approach in Southeast Asia and offers some explanation and assessment of it. The paper then argues that the low emphasis on supporting liberal and democratic institutions, practices, and norms is not just a lost opportunity for Canberra but is counterproductive to its stated interests and even dangerous in some circumstances. It ends with some suggestions about how Australia can better improve this element of its statecraft whilst avoiding the mistakes and overreach that have characterised some democracy promotion efforts of Western allies.

Australian mindset and approach

Australia is a proud democracy and promotes its political institutions and values as a virtue and example to its partners in Southeast Asia. There is also official and widespread consensus that “Authoritarianism is becoming entrenched in mainland Southeast Asia, while electoral democracies in maritime Southeast Asia are increasingly illiberal.”55

Even so, there is a reluctance to engage more actively and explicitly in ‘democracy support’ with these same countries. As a Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade submission to the 2023 parliamentary inquiry into “supporting democracy in our region” puts it, “in the [Southeast Asian] region, governing systems range from established (but varied types of) democracies to authoritarian regimes. Australia’s approach to supporting democracy and governance in the Asian region is therefore highly differentiated — politically and practically.”56 This causes Canberra to be “respectful of different types of political and governance systems”57 as Australia “cannot and should not seek to impose change.”58

Indeed, expert commentators and observers of Australian foreign policy (especially those focusing on Southeast Asia) warn against a ‘systems competition’ between democracy and autocracy given the diverse range of ‘democratic’ institutions in Southeast Asia. The argument is based on the notion that drawing a hard distinction between democratic and autocratic regimes is not a useful one when it comes to political ethics and policy. Illiberal societies can have democratic institutions while relatively liberal societies might not enjoy what one might consider ‘free and fair elections.’ Moreover, adopting an ideologically-driven ‘democracy promotion’ framework and approach is “likely to create distance between the world’s democracies and the regional countries Washington (and Canberra) wants to assist.”59

Additionally, the Australian approach cannot be glibly characterised and dismissed simply as a desire ‘not to offend’ Southeast Asian regimes and populations, even though an element of this holds true. Unlike more distant and powerful countries such as the United States, Australia is not a superpower and its proximity to Southeast Asia renders it exposed and vulnerable to any deterioration in its relationships, especially with the maritime Southeast Asian states. For example, Australia could not afford the downturn in relations with Thailand which the United States endured after the Obama administration downgraded relations following the 2014 military coup in Bangkok. It is for this reason that Australia takes a self-described ‘pragmatic’ rather than ideological approach in the region.60

The ‘pragmatic’ approach has several characteristics which have endured over several decades up to the current Albanese government. In Southeast Asia, democracy promotion or support appears to be subsumed under the broader umbrella of ‘state-building’ with the explicit promotion of democracy not being a significant objective. Within the framework of ‘state-building’ in Southeast Asia (which is the author’s nomenclature), there seem to be six broad elements which are listed below (not necessarily in order of prioritisation):

- Election support: election monitoring, logistics support for elections, and technical assistance to strengthen election bodies.

- Strengthening governance and accountability institutions: support to audit offices, ombudsmen, parliaments, service delivery, regulatory and law enforcement agencies, anti-corruption work, public financial management, and economic governance and reform.