With the inauguration of President Joe Biden on 20 January 2021, there was a sense that the “adults were back” (Cillizza, 2021) and the United States would return to ‘normalcy.’ All eyes were on the new president’s Build Back Better plan. Some mainstream media outlets even compared Biden’s approach to FDR’s New Deal (Gergen, 2021) – implying that, like the wartime president, Biden and his bill would transform America through infrastructure and stimulus packages, lifting it out of the ravages of a pandemic related depression.

Much was also expected internationally, and the president did not disappoint in his rhetoric. At both an address to the Department of State and to the delegates at the Munich Security Conference last year, Biden declared: “America is back. America is back” (White House, 2021). With these and other addresses, the president brought promises of renewed international engagement, especially with respect to the Indo-Pacific where he vowed “to work closely with allies and partners to compete with China” (Townshend, et al., 2021). Further, on his first day in office, Biden re-joined the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, and the WHO, signalling a renewed respect for multilateral agreements and fora (Macia, 2021) (Mai, 2021).

From Biden’s handling of the Southern border to soaring COVID cases and rising inflation, it’s clear that there is a lot going on for which Biden is being held responsible.

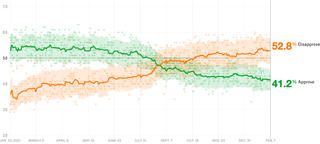

This apparent divergence from Donald Trump’s modus operandi played out favourably in the polls. In January 2021, 53 per cent of Americans approved of Joe Biden while just 36 per cent disapproved (Fivethirtyeight, 2021). Comparatively, at the end of his presidency, a mere 38 per cent of Americans approved of Trump, while 57 per cent disapproved (Fivethirtyeight, 2021). Similarly, in the first half of this year, 61 per cent of Australians trusted the United States to act responsibly in the world, a notable 10-point increase from last year (Hurley, 2021).

Yet, one year into his presidency more Americans disapprove (53 per cent) than approve (42 per cent) of Joe Biden – representing a marked turnaround in opinion (Fivethirtyeight, 2021). It is impossible to disentangle all the issues that have contributed to this drop. From Biden’s handling of the Southern border to soaring COVID cases (Towey & Rattner, 2021) and rising inflation, it’s clear that there is a lot going on for which Biden is being held responsible. Importantly, there was a pronounced deterioration in Biden’s approval from around mid-August to mid-September last year (Fivethirtyeight, 2021).

Figure 1. President Joe Biden's approval rating

Consequently, it’s not misguided to suggest that mismanagement in the US withdrawal from Afghanistan was a major factor in Biden’s falling approval ratings. Misleading claims that “the Afghani army… [constituting more than] 300,000” troops (Dale, 2021) would resist the Taliban, and that horrifying evacuation scenes were “manifestly not Saigon” (Blinken, 2021), set the administration up for a PR disaster.

While there has been no significant international polling on the United States or Biden since mid-2021, it’s reasonable to assume that Afghanistan had a similar effect on global perceptions about the administration’s competency. This was potentially compounded by the president dismissing European leaders’ pleas to extend the date of evacuation past 31 August (Sandford, 2021) and reportedly ignoring Boris Johnson’s calls for 36 critical hours (Chamberlain, 2021).

In addition to mismanagement in Afghanistan, Biden has been criticised internationally over the decision to authorise AUKUS – a trilateral security pact between the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom. Notwithstanding the pact’s benefits and its inherent multilateralism, it received backlash from some allies in Asia and Europe. Both Malaysia and Indonesia labelled it antagonistic, suggesting it could potentially set off a regional arms race with China (Weber, 2021). France, whose submarine deal with Australia was supplanted by the pact, declared it a “stab in the back” (Giordano & Woodcock, 2021). Whatever the transitory politics or serious concerns of these responses, President Biden’s multilateral approach to the Indo-Pacific is perhaps more selective and Anglo-centric than many were expecting.

The souring of opinion towards Biden and some of his actions over the year imply that the reality has fallen short of the President’s rhetoric and international expectations.

That said, Biden has demonstrated a commitment to multilateralism, more so than his predecessor.

While former president Trump placed great importance on the Quad and the Indo-Pacific, Biden has amplified this, formally coordinating the strategic goals of the United States with Japan, Australia, and India at the September Leader’s Summit last year (Smith, 2021). Importantly, this meeting was the first in-person Leader’s Summit – highlighting the significance of the Security Dialogue to the president.

Moreover, Trump shunned multilateral climate change meetings and commitments such as the Paris Climate Accord. And when he did attend international conferences, for example, the 2019 UN Climate Summit, his presence elicited surprise (Borger, 2019). Biden on the other hand, was expected at the COP26 Summit in October and attended enthusiastically (though images of him sleeping through speeches drew doubt) (Sky News, 2021). Finally, Biden has put Trump’s legacy of European trade disputes to rest (Kandel, 2021), reaching a multilateral agreement on US-EU aluminium and steel.

While these suggest a commitment to allies and an ‘international agenda’, we should not be surprised when Biden acts unilaterally or with selective multilateralism – such as in the cases of Afghanistan and AUKUS.

So is America really ‘back?’ It is undeniable that the president has taken more care than his predecessor to balance the dual imperatives of national interest with commitments to key allies and partners. Nevertheless, the souring of opinion towards Biden and some of his actions over the year imply that the reality has fallen short of the President’s rhetoric and international expectations.

.jpg?rect=0,80,3000,1989&fp-x=0.5&fp-y=0.44772296905517583&w=320&h=212&fit=crop&crop=focalpoint&auto=format)