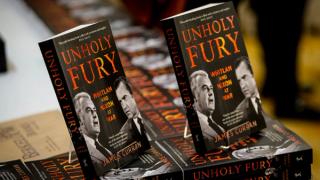

Unholy Fury: Whitlam and Nixon at War by James Curran

Reviewed by Bob Carr

It's scripted, out of the State Department handbook, for any Washington meeting between Australian and American leaders. "We have no closer friend," declares the American, and then — hearing the cliché bounce off the Federation-era chandelier — adds, "No, no, no — this time … it's true."

In fact, the Australian–US relationship is so comfortable it's hard to imagine a time when the White House ignored a request for a meeting from an Australian Prime Minister – to freeze the bastard out. Or a time when the Americans thought about giving up on ANZUS and plucking their communications bases out of the Australian desert. Or an Australian Prime Minister, in a letter to the President, putting the US on the same level as North Vietnam and instructing our diplomats to work at being less craven.

Dumping ANZUS? Giving up the facilities? Less Craven?

Sydney University academic James Curran has mined the US archives to produce a narrative of the one single breakdown in US–Australian relations since ANZUS was ratified in 1951.

The coincidence of Gough Whitlam and Richard Nixon did it: in one corner, a scornful and impatient liberal internationalist; in the other, a paranoid Republican being resisted by the North Vietnamese who were offering no compromises in the Paris peace talks. Nixon's response: 120 raids a day by B-52 bombers or "Stratofortresses" to blanket bomb the country.

This 1972 "Christmas bombing" did it. Whitlam sent a letter of protest to Nixon in which he indelicately said Australia would enlist East Asian nations in an appeal to the US and North Vietnam to reopen negotiations.

To Washington, this was unthinkable. Whitlam had put the United States on the same level as its Communist enemy. Henry Kissinger exploded, branding Whitlam's letter "an absolute outrage" and a "cheap little manoeuvre". Suddenly Australia, under its new government, was on a par with neutral Sweden.

Whitlam's scorn for Nixon grew. Curran produces notes from a 1973 meeting with senior diplomats — the first time the notes have been exposed — in which Whitlam asserts there was more in the alliance for the US than for Australia. Meanwhile, at Camp David, Kissinger was saying, "From the minute the Vietnam War ends, the Australians will need us one hell of a lot more than we need them."

The leaders were coming from different directions, as Curran says, "Nixon desperate to be free of Vietnam; Whitlam eager to reset Australia's international stance."

Left-wing ministers and the Maritime Union joined the fray, opening up on the US. Whitlam was slow to disown them. In fact, in January 1973 in his first meeting with the US Ambassador he said that any attempt to "screw us or bounce us" would mean arrangements for US intelligence facilities on Australian soil might become "a matter of contention here".

This was a loose-lipped, ill-considered strike at American anxieties. Those facilities gave America 40 minutes' notice of missiles aimed at its cities. They sent communications to its nuclear-armed submarines.

Sainted Gough fell a little short of the diplomatic challenge dealing with an increasingly wounded Nixon, even using Question Time in May 1973 to take a pot-shot at the Watergate scandal. "I really shouldn't have said that," he conceded, leaving the House (again, a find by Curran). The new US Ambassador, Marshall Green, a professional diplomat, was sent to smooth things. He warned Washington that if it continued to freeze Whitlam out of a White House visit they risked surging Australian nationalism putting at risk the US defence facilities.

Yet how refreshing that Whitlam could declare, "For all its enduring importance, adherence to ANZUS does not constitute a foreign policy." Today, under Coalition and Labor governments, it sometimes looks the biggest part of our international personality.

Curran records the sad attempts in the '60s by Coalition prime ministers to get America to declare ANZUS would apply if Australia slipped into conflict with Indonesia. Irritated, on half a dozen occasions, the US rejected this, saying Indonesia was too important. From the start, there was never automaticity in ANZUS. Perceptive that Whitlam in 1953, in his first foreign policy speech in Parliament, put his finger on the ambiguity at the heart of ANZUS, asking: "Are we to be embroiled on behalf of the Americans if there is an armed attack on any United States armed forces in an area where they are conducting some unilateral campaign ...?"

In support of the Japanese over rocky outcrops, for example?

The US response to Australia about Indonesia in the 1960s entitles us, now, to decline being dragged into war over the Senkaku–Diaoyu Islands.

Curran says there is no documentary evidence to conclude the threat to US intelligence facilities got the CIA involved in Whitlam's dismissal. Whether Governor-General John Kerr picked up US concerns and they deepened his contempt for the government is something I consider possible. But Curran concludes it has absolutely no documentary support. On that affair, as on everything else, 300 pages of good writing and fine judgement make me inclined to trust this author.