Introduction

A brief note on impeachment, removal from office, and the US Constitution

Article 2, Section 4 of the Constitution of the United States provides the mechanism whereby the legislative branch can remove the president:

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

Impeachment and removal from office is not the same as a no-confidence motion in a Westminster system. No-confidence motions can be moved at will and without any constitutional requirement that the motion be moved “with cause” or accompanied with claims of criminal behaviour by the executive. A government or prime minister losing a no confidence motion in a Westminster system is expected to resign immediately, consistent with the principle of responsible government.

In the US system, removing a president via impeachment proceedings was designed as a rough analogue, a mechanism by which the executive branch of US government can be held accountable to the legislative branch. This ultimate sanction — removal from office — was designed by the American Founders as an extreme measure. Hence the US Constitution’s reference to “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors” as the circumstances triggering a president’s impeachment and removal from office.

Article 1, Section 2 provides that the House of Representatives “shall have the sole Power of Impeachment”. Impeachment is thus an action of the House of Representatives, requiring only a majority vote of the House. As Article 2, Section 4 makes clear, conviction in the Senate after impeachment in the House of Representatives is required for a president to be removed from office.

Article 1, Section 3 provides that in such a trial “no person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two-thirds of the Members present”.

An analogy from criminal law might be to consider impeachment by the House of Representatives as akin to indictment ahead of a trial in the Senate. The Constitution is explicit about the fact that the Senate’s consideration of an impeachment matter is a trial. The word “try” appears in Article 1, Section 2 and Article 1, Section 3 also provides that “When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside”.

Members of Congress are not jurors or jurists. They are politicians, casting votes on impeachment and removal from office in public, accountable not to an appeals court, but to voters at the ballot box.

None of this should distract us from the fact that impeachment is an intensely political process. While the Senate does hold a trial — and the Constitution refers to criminal acts in Article 2, Section 4 — the House and the Senate have near complete autonomy as to what might constitute “high Crimes and Misdemeanors”, the admissibility of evidence and procedure. Members of Congress are not jurors or jurists. They are politicians, casting votes on impeachment and removal from office in public, accountable not to an appeals court, but to voters at the ballot box. The legal formalisms in the language and procedures around impeachment are not as important substantively to the impeachment process — and its outcome — as the political imperatives confronting members of Congress and the president.

Removal from office and other penalties

Removal from office follows a conviction (Article 2, Section 4, quoted above). But Article 1, Section 3 also provides that:

Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.

That is, criminal proceedings can still be brought against a former president after a conviction, highlighting that impeachment proceedings and removal from office do not necessarily involve nor resolve any question of criminal guilt or innocence. Impeachment, trial in the Senate and removal from office are designed to “maintain constitutional government”, not to punish the person in question.1 In the 65th essay in the Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton, one of the so-called ‘Founding Fathers’ of the United States, stated that impeachment concerned:

those offences which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.

To date, the US Senate has conducted formal impeachment proceedings 19 times, resulting in seven acquittals, eight convictions, three dismissals, and one resignation with no further action.2

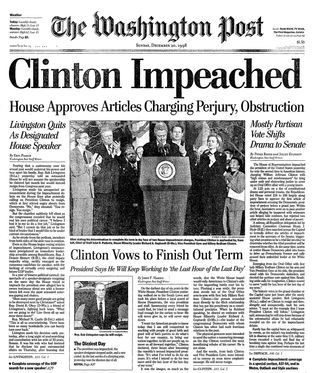

Just two of these 19 actions concerned presidents: Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1998. Neither was convicted by the Senate, meaning that no president has ever been removed from office after being impeached.

Surviving impeachment: The president’s party decides

Simon Jackman

A president can survive impeachment under one and only one condition: that the president continues to enjoy the support of most of the members of his own party.

Impeaching a president requires a majority vote of the House of Representatives. This could well be an easy obstacle to surmount, since it is often the case that a president’s party is not the majority party in the House.3 A much higher hurdle is securing a two-thirds vote for conviction and removal from office in the Senate. In the post-New-Deal era, no president has ever confronted a Senate where the opposing party had a two-thirds majority. 4 Removal from office therefore requires at least some — if not many — of a president’s own partisans to defect.

History bears out this simple fact about impeachment. In 1974, Richard Nixon resigned in the face of crumbling support among Republicans — members of Congress and rank and file alike — which had made impeachment and conviction all but assured. Conversely, in 1998 Bill Clinton was impeached with Republican majorities in the House of Representatives and Senate, but with near universal opposition to impeachment among Democratic House members. No Democratic senator voted for Clinton’s conviction in the Senate.

What role does public opinion play in accounting for the different fates of Nixon and Clinton? How can we measure the likelihood that a president’s co-partisans might be prone to abandoning the president? Are there lessons to be learned that might be applicable to an assessment of public opinion with respect to Trump?

Presidential approval: Nixon, Clinton and Trump

Figure 1 shows levels of in-party presidential approval for presidents from Eisenhower to Obama, as measured by Gallup surveys. Approval for Donald Trump is also shown (in red).

Figure 1

The collapse in Nixon’s standing with the American public over calendar year 1973, as displayed in Figure 2, is stark and a critical precursor to the House Judiciary Committee pursuing Nixon’s impeachment. At the time of Nixon’s re-inauguration in January 1973, his approval ratings stood at 66 per cent, the highest approval rating Gallup recorded for Nixon. Recall that throughout 1973 Nixon aides were resigning or being fired, the Senate “Watergate Committee” held sensational, televised hearings in May, and Nixon attempted to shut down the Watergate investigation in the “Saturday Night Massacre” (20 October). By July 1973, Nixon’s approval ratings had dropped below 40 per cent and continued to fall below 30 per cent by October. Nixon’s approval ratings remained mired in the 20-30 per cent range as the House Judiciary Committee conducted its investigation. Nixon’s last 10 months in office saw him with approval ratings never above the high 20s, a testament to his dwindling political capital and a strong indicator that conviction and removal from office would be the result of impeachment.

Nixon’s last 10 months in office saw him with approval ratings never above the high 20s, a testament to his dwindling political capital and a strong indicator that conviction and removal from office would be the result of impeachment.

In contrast, Bill Clinton’s approval ratings had been gradually increasing from the summer of 1994 onwards. By early 1998, Clinton was recording 60 per cent approval ratings in Gallup polls. The Gallup poll conducted immediately after the Lewinsky scandal — and Clinton’s famous televised denial — showed a nine point increase in Clinton’s approval ratings. Throughout 1998, even as Starr’s investigation reached its crescendo — questioning Lewinsky in July and August of 1998 — Clinton’s approval ratings remained at or above 60 per cent. The delivery and publication of Starr’s report and Clinton’s impeachment by the House of Representatives did nothing to dent his approval ratings. A Gallup poll fielded as the House impeached Clinton found his approval ratings to be 73 per cent, a 10-point increase on the preceding Gallup poll. Throughout Clinton’s trial in the Senate his approval ratings stayed above 65 per cent. By 2000, Clinton’s approval rating was around 60 per cent; a post-election bump saw the outgoing, two-term president leave office with approval ratings in high 60s.

The contrast with Nixon’s case could not be starker. Clinton could be confident of staring down impeachment by the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, secure in the knowledge that with approval ratings in the high 60s — and sometimes higher — Democratic senators would not vote to convict. Indeed, no Democratic senator voted for Clinton’s conviction.

In-party versus out-party support

A critical element of political support for a president is the distinction between approval among partisans of the president’s party, among independents and among partisans of the “out-party”.

Few presidents have high levels of approval from out-party partisans, a tendency that has become more pronounced over time as levels of partisan and ideological polarisation have risen in the United States. The average difference in presidential approval ratings between Democrats and Republicans has increased from a range of 26 to 40 points under Eisenhower to Carter, to 52 points under Reagan, 55 points under Clinton, 60 points under George W. Bush and 71 points under Obama. The first months of Trump’s presidency produced a 77-point average inter-party difference in approval ratings for Trump, an unprecedented level of partisan polarisation within presidential approval which has grown over the course of his presidency.

The political logic of impeachment demands we study the standing of the president with partisans of the president’s party. This suggests that polling data tapping the president’s approval among partisans of the president’s party are a critical barometer of the chances that a president will be impeached or removed from office.

Figure 2: Levels of approval for Nixon, Clinton and Trump, by party identification

In Figure 2, I present levels of approval for Nixon, Clinton and Trump, by party identification. The precipitous slide in Nixon’s approval ratings through 1973 occurs across all partisan groups but is especially pronounced among Independents. Republicans begin 1973 with approval ratings of Nixon of around 90 per cent, as Nixon was re-inaugurated after the 1972 election. By the time of the House Judiciary Committee investigation in late 1973, Nixon’s in-party approval rating had dropped to below 60 per cent, reaching 50 per cent by the time the Committee adopted articles of impeachment against Nixon. This made Nixon especially vulnerable once the “smoking gun” conversation was made public, with support among Republicans insufficient to stave off a two-thirds vote for conviction had impeachment proceeded to the Senate.

Clinton never received high levels of support from Republicans, averaging a 27 per cent approval rating from Republicans over the eight years of his presidency. Importantly, as the Republican-controlled House moved to impeach Clinton, his approval rating among Democrats continued to climb, sitting in the high 80 per cent to low 90 per cent in late 1998 into early 1999. During Clinton’s trial in the Senate, Democrats gave Clinton approval ratings of 94 per cent, among the very highest in-party approval ratings observed over the 64 years of Gallup approval data. Roughly two-thirds of political independents approved of Clinton’s performance through this period, further evidence of the fact that there was no meaningful political appetite for removing Clinton from office outside of the Republican party.

During Clinton’s trial in the Senate, Democrats gave Clinton approval ratings of 94 per cent, among the very highest in-party approval ratings observed over the 64 years of Gallup approval data.

These historical comparisons help us put Trump’s approval ratings in context. To be sure, Trump’s overall approval ratings are not high, especially relative to other presidents at this early stage of a presidential term. Trump’s approval numbers have fallen slightly over his term thus far, but the bulk of that movement has come from Democrats and Independents. Since late April 2017, less than 10 per cent of Democrats have approved of Trump; political independents rate Trump in the low 30s, down from high 30s to 40 per cent shortly after Trump’s inauguration. Republican support for Trump has cooled somewhat, but continues to be overwhelmingly positive, sitting somewhere in the low to mid 80s in the last month of polls, down from the high 80s recorded in the opening months of his presidency.

This level of in-party support is typical for presidents in recent decades, as depicted in Figure 1. Trump enjoys levels of support from Republicans that are indistinguishable from the levels of in-party support Lyndon Johnson, Nixon, and Reagan had at the comparable stage of their presidencies. Trump is underperforming Obama and George W. Bush, but overperforming Carter, Ford and Clinton. In short, there is nothing especially noteworthy about the high levels of in-party support Trump currently has. Like almost all presidents early in their first term, the presidents' fellow partisans overwhelmingly support the incumbent president. These approval data strongly suggest that President Trump will not face an impeachment threat in the current Congress.

The intensely political nature of impeachment — coupled with historically high levels of partisanship in contemporary US politics — makes it extremely unlikely that President Trump will be removed from office.

The impeachment inquiries underway would have to reveal new facts that damage the president among Republican partisans and Republican members of Congress. A remarkable feature of the Trump presidency is that his standing among Republicans has barely shifted over the course of his presidency, despite the criminal convictions of former aides, the Mueller probe, and an array of allegations of self-dealing.

President Trump currently has an approval rating among Republicans in high 80 per cent range. Until Republican support for Trump drops precipitously — closer to the 50 per cent levels recorded by Nixon towards the end of his presidency — removal from office would seem out of the question.

No Democratic senator voted for conviction in the trial of Bill Clinton. If — as seems quite likely — the House of Representatives impeaches Donald Trump, we could see history repeating itself, with no Republican Senator voting for conviction.

Great and dangerous offences: A short history of impeachment

Charles Edel

To the early Americans who had fought a war against the monarchy, both the accumulation and arbitrary use of power was dangerous. Historian Jeffrey Engel posits that the central question of their entire era was “what form of government could therefore be entrusted with the power it required, without simultaneously employing that power to undermine liberty? More specifically, in whose hands could such power possibly be trusted?”5 The answer they came up with was a mixed government which including institutionalised checks and balances between the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government; regular elections; and, as a last line of defence, impeachment.6 In this reading, impeachment became central not only to the US constitution but to the American idea of liberty — and was intended as a safeguard against the despotic accumulation and use of power by a president.

Impeachment became central not only to the US constitution but to the American idea of liberty — and was intended as a safeguard against the despotic accumulation and use of power by a president.

The framers of the US constitution settled on “treason, bribery, and high crimes and misdemeanors” as rationales for impeachment. The first two were clear enough from a definitional perspective, but the framers found them not sufficiently broad to serve as a safeguard. Criminality was considered neither necessary nor sufficient, even if it made the case clearer and more comfortable.7 The constitutional debates reveal that the addition of “high crimes and misdemeanors” was key as it signified the belief that an impeachable offence need not be a crime at all. Borrowing this phrase from British legal practice, the Constitution’s authors reasoned that there were “many great and dangerous offenses” which would not necessarily meet the precise definitions of treason or bribery, but which nevertheless would constitute an egregious abuse of power, an imperilling of national security, or a betrayal of national trust.8

Such offences were understood by the Constitution’s writers as profound political crimes committed against the state with grievous implications to the proper functioning of the country’s democratic processes.9 They believed that presidents ought to be removable, not for general and vague reasons, but rather for specific abuses of the public trust.10 The Constitution left it to the judgment of the House of Representatives and Senate to determine when, in the words of Alexander Hamilton, “the abuse or violation of some public trust” amounted to “injuries done immediately to the society itself”, and required removing the president from office, lest his continued occupation of the presidency do further damage.11 While the process would likely prove highly destabilising and leave lasting scars on the country, it was also deemed necessary.

Of precedents and presidents

Over the past 230 years, the House has initiated impeachment proceedings more than 60 times, although it voted to impeach just 19 officials.12 Of those, 15 were federal judges, two were presidents (Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton), one was a senator (William Blount of Tennessee in 1797), and one was a cabinet official (William Belknap in 1876). And, of those, the Senate found eight guilty (all judges), acquitted seven, and disqualified one for technical reasons, and three of those officials resigned before they were tried. There have been multiple congressional attempts at presidential impeachment which failed to secure the required majority vote. Successful presidential impeachment has only two historical precedents — as Nixon resigned before he could be formally impeached.

President Andrew Johnson (1868)

In the first case of presidential impeachment, the House of Representatives impeached President Johnson for firing the popular Secretary of War without their approval.13 In fact, this was merely the pretext for impeaching him, as Congress had been searching for a cause to remove a president who had obstructed its legislative program.14 Johnson had succeeded Abraham Lincoln after the latter’s assassination and repeatedly frustrated the congressional majority’s desire to politically reconstruct the southern US states after their defeat in the Civil War.

Johnson, a southern Democrat, proved far less inclined to provide sufficient protections for the freed slaves or harsh punishment for the Confederate leaders than congressional Republicans demanded. Beyond what seemed to them noxious policy choices, overt racism, and the use of the US Attorney General to circumscribe congressional statues on Reconstruction, Johnson repeatedly offended congressional leaders with his attacks on Congress, promotion of conspiracy theories, narcissism and persecution complex.

These, however, failed to be credible grounds for impeachment, so Congress passed a law, subsequently ruled unconstitutional, which forbade the president from firing cabinet officials without obtaining congressional approval. This was specifically designed to trigger impeachment by stating that violation constituted a “high misdemeanour”. So, when Johnson fired the Secretary of War — a holdover from Lincoln’s tenure and a close ally of congressional Republicans in pushing for a more assertive set of Reconstruction policies — the House voted eleven articles of impeachment, revolving around his firing of the Secretary of War and general contempt of Congress.

After a ten-week trial, the Senate acquitted Johnson by the narrowest of margins — 35 to 19 — falling one vote short of the required two-thirds majority required for conviction, despite the fact that Republicans held overwhelming majorities in both the House and Senate.

According to constitutional scholar Cass Sunstein, this acquittal underscored that “loathing a president is not sufficient grounds for impeaching him”. 15 Moreover, it underscored that in the American system, the president is not subject to a vote of no-confidence. For the next hundred years, Johnson’s acquittal set a precedent that a president’s obnoxiousness, incompetence, violations of political norms, and policy preferences were all insufficient grounds for removal from office.

President Richard Nixon (1974)

The next case came more than a century later when Richard Nixon resigned from office prior to being impeached by the House.16 His resignation was the result of the ongoing Watergate investigation, which involved a break-in and bugging of the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters, and a subsequent cover-up by the White House. Investigations by the press, the Department of Justice, and Congress revealed that Nixon had used his official position to spy on domestic political opponents, paid “hush money” to the burglars after they were caught, attempted to use the CIA to thwart the FBI’s investigation, and used federal agencies like the IRS as weapons against his political enemies. As the House investigation proceeded, Nixon refused to comply with the Judiciary Committees’ subpoenas, calling such efforts a “witch hunt” and complaining that he was the most prosecuted president since Abraham Lincoln.17

The Judiciary Committee sent three articles of impeachment to the House, charging that the president obstructed the investigation of the Watergate burglary, used the power of his office for personal and political gain, and had acted in contempt of Congress by refusing to provide the committee with requested materials. As solid evidence of Nixon’s wrongdoings emerged, public and congressional support collapsed astonishingly quickly. But Nixon resigned before the full House could vote on the articles of impeachment, and just two days after Republican senators informed him that support was fast ebbing away from him.

Nixon’s experience had multiple implications. In the aftermath of his resignation, faith in government plummeted and has struggled to recover to pre-Watergate levels.18 Nixon’s experiences also demonstrated that a president’s past popularity — Nixon had won re-election in 1972 with more than 60 per cent of the vote — was an insufficient prohibition against impeachment once an accumulation of evidence of grave presidential wrongdoing appeared. The movement of public opinion also played a major role in this case. “The law case will be decided by the PR case,” Nixon observed in March 1974.19 Here, Nixon was prescient as once his support collapsed it did so with astonishing rapidity.

This case also holds a final note on the conduct of national security. Concerned that the president might do something desperate in his final days, the Pentagon leadership purportedly instructed various commands that if they received orders from the White House to use force, they should first confirm them with the Secretary of Defense.20 This hardly stands as a precedent but does suggest that under extreme political duress, senior officials will explore how to use their responsibilities, within the chain of command, to constrain erratic and dangerous decision.

President William Clinton (1998-99)

The most recent example of impeachment comes from 1998-99 when Bill Clinton was impeached by the House, and acquitted by the Senate.21 This process stemmed from a 1994 investigation into the propriety of the Clintons’ previous real estate investments. Kenneth Starr oversaw the investigation and, despite finding no evidence of prosecutable wrongdoing in connection with those investments, repeatedly had his authority expanded to investigate various charges of presidential wrongdoing, including a sexual harassment lawsuit brought against Clinton. In the course of his investigation, Starr encountered evidence of alleged wrongdoings in Clinton’s relationship with Monica Lewinsky, a White House intern, and his subsequent efforts to cover up that relationship. Starr produced a lengthy report which concluded that “there is Substantial and Credible Information that President Clinton Committed Acts that May Constitute Grounds for an Impeachment”, and repeatedly pressed Congress to impeach Clinton.22

The House voted to impeach Clinton, 228 to 206, along partisan lines, charging him with two articles of impeachment: perjury to a grand jury and obstruction of justice.23 While Democratic and Republican senators worked to ensure that the impeachment process received bipartisan support in the Senate, the impeachment itself was seen as a highly partisan prosecution of the president.24 As a result, Clinton’s approval ratings rose steadily during the impeachment trial to 73 per cent, making conviction politically challenging, no matter the merits of the case.25 Fifty senators voted to convict Clinton on obstruction of justice and 45 on perjury — both falling well short of the 67 votes required to remove him from office and, as a result, acquitting him on both charges.

According to Peter Baker, who covered Clinton’s impeachment for the New York Times “each side sought to shape the public narrative to convince Americans that the other side was violating the norms of America’s constitutional democracy”. 26 Congressional Republicans pointed to the president’s false statements and obstruction of justice in an effort to equate Clinton and Nixon’s wrongdoings, while Democrats — and most of the country — thought that lying about a sexual relationship did not come close to spying on the opposition, paying hush money to the burglars, or harassing critics of a sitting president for electoral advantage.27

Ultimately, the question the senate made their judgments on was not whether Clinton had lied, sullied the office, or acted to obstruct justice in the civil lawsuit. As the Senate was constitutionally empowered to act as both judge and jury, the question they ultimately rendered judgment on was whether the president’s actions had harmed American society, done injury to the state, and were likely to be replicated if he were left in office. Most Americans and a sufficient number of senators believed the answer was no on all counts.

History suggests several conclusions about the intended use of impeachment, the parameters drawn around its employment, and the elasticity it was given to ensure its suitability for a variety of situations.

First, there is an incredibly high bar set for impeaching a president — and an even higher one for their removal. That does not, of course, render impeachment moot. Rather, it depends on a dynamic interplay between the nature of the allegations, the credibility of the evidence, and the broader popularity of the president. And, it is also likely to depend on questions surrounding whether the case for removing the president is best constructed as a narrow charge, revolving around specific charges, or a broad case, based on a larger pattern of behaviour.

When articles of impeachment are voted on, and the president’s political trial commences, it will largely subsume all other business of the US government, shrinking its bandwidth and narrowing its focus for the duration of the process.

Because impeachment makes such a grave charge it was intended to be both political and public. As such, when articles of impeachment are voted on, and the president’s political trial commences, it will largely subsume all other business of the US government, shrinking its bandwidth and narrowing its focus for the duration of the process.

Additionally, impeachment cannot occur — or, at least is highly unlikely to result in a conviction — if it is based on policy differences, partisan disagreements, or offences deemed inappropriate, or even criminal in nature, but not harmful to the nation’s safety or the integrity of its democratic processes. Its utility, and its chances of success, however, are likely to rise in an instance where there is compelling evidence, popular outrage and at least some bipartisan support.

But it is precisely because of the contested nature and depth of the alleged harm done that impeachment has always been a ferociously partisan and highly divisive affair. As Alexander Hamilton foresaw more than two centuries ago, impeachment will “agitate the passions of the whole community”, connect to “pre-existing factions”, and the outcome will be determined less by “real demonstrations of innocence or guilt”, and more by the competitive strength of the parties.28

Finally, as the Founders envisioned, debate will ultimately hinge on what the public — and ultimately Congress — believes constitutes unacceptable political behaviour. As the debate evolves, history suggests that public opinion on that is unlikely to remain static.

The foreign policy mess — a prelude and coda to impeachment

Gorana Grgic

The impeachment inquiry into Donald Trump is unique in that it has been triggered by a matter in the domain of foreign policy. Unlike Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton, who saw the articles of impeachment brought against them over malfeasances that stemmed from domestic issues, President Trump’s misconduct pertains to his (mis)management of foreign policy.

It is thus important to appreciate the latitude of presidential powers in the foreign policy realm and understand how the Trump administration has deviated from the norms in terms of staffing, policy process and diplomacy. The observable dysfunction has significant implications for the impeachment process, as well as US relations with Ukraine and the rest of the world.

Presidential powers in foreign policy and why they matter for impeachment

The US Constitution invites the executive and legislative branches “to struggle for the privilege of directing American foreign policy”.29 Yet, one of the long-standing truisms of US politics is that the president holds much greater sway over this realm of policymaking than the Congress. The large opus of empirical studies combined with the historical record have shown that when it comes to foreign policy agenda-setting and decisionmaking, the executive branch of the US government, and specifically the president, tends to operate with fewer constraints than in the domestic policymaking context.30

This was not the Founding Fathers’ intention. When they were drafting the constitution, guided by the principles of the separation of powers and checks and balances, they sought to ensure that the head of the executive branch would not grow omnipotent in any sphere of governance.31 Yet, as the US government has developed and grown in size, presidents have increasingly been able to exercise foreign policy powers independent from the Congress as a result of the expanding bureaucracy they came to manage, historical precedents32, contingencies, as well as shifting public expectations.

As the US government has developed and grown in size, presidents have increasingly been able to exercise foreign policy powers independent from the Congress as a result of the expanding bureaucracy they came to manage, historical precedents, contingencies, as well as shifting public expectations.

As the chief of the executive branch, the US president has significant powers to organise and staff the foreign policy bureaucracy. Moreover, as the chief diplomat, the president enjoys the first-mover advantage vis-à-vis the legislature in negotiating with the foreign counterparts. More importantly, working under the banner of national security, the president enjoys substantial secrecy in handling of foreign affairs.

Given the significant powers a US president wields in this space, the possibility of abuse of the office is present almost by default. However, there is also a view that echoes the famous (and highly contested) Nixon’s dictum “when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal” precisely because of the leeway in policymaking that presidents have come to enjoy on the foreign policy front. The debate between these two views encapsulates the core difference between the two opposing sides in the current impeachment process against President Trump.

Foreign policy (mis)management under Trump

The mismanagement of the foreign policy process has been more than evident during the three years of the Trump presidency. Haphazard decisions on hiring and firing, a highly informal approach to policymaking, and a disdain for the conventions of foreign policy craft have major consequences for the impeachment process and beyond.

When President Trump came to office, about 4,000 posts across the entire federal bureaucracy were awaiting his nominations. At the State Department and Department of Defense alone, the new administration needed to fill more than 700 vacant spots — ranging from the department secretaries and agency directors to ambassadors and special envoys.33 More than 1,000 of the appointees needed to go through the Senate confirmation. Most of those working at the White House, as part of the Executive Office of the President, were spared the hearings and votes on the Capitol Hill as they work for and report directly to the president.

The hollowing out of some of the key departments in charge of foreign policy is both the product of the president’s agenda, as well as a reaction to it. For instance, the State Department experienced a large number of delayed appointments for key positions34, as well as an exodus of career foreign service officers who did not want to serve the new administration.35 While the push to select major donors and supporters of the president as political appointees is not a new phenomenon in presidential administrations, the Trump administration’s practices in this area have egregiously complicated policy implementation and led to considerable tensions between the career officers and political appointees.36

The early days of the impeachment inquiry have demonstrated precisely how the experienced career diplomats had a difficult time dealing with the political appointees and presidential advisors over the Ukraine policy. Perhaps the starkest example came from the former US ambassador to Ukraine Marie Yovanovitch, who detailed in her testimony to Congress how the president’s personal attorney Rudy Giuliani instigated a smear campaign against her, as well as how the president’s pick for the US ambassador to the European Union, Gordon Sondland, urged her to tweet favourably about the president.37 The slew of high-profile resignations at the State Department over the disagreement with the Trump administration’s dealings with Ukraine further builds the mismanagement case.38

The early days of the impeachment inquiry have demonstrated precisely how the experienced career diplomats had a difficult time dealing with the political appointees and presidential advisors over the Ukraine policy.

Furthermore, the overall record level of staff turnover has reflected poorly on the policy process. The Trump administration has experienced nearly 80 per cent turnover among the top echelon of appointees — a figure that surpasses all of his predecessors who served four-year terms.39 The consequences of such an unprecedented rate of change are dire. When the heads of departments and agencies are missing, or are serving only in acting capacity, it is difficult to coordinate policy implementation and plan strategically. It also opens up the space for informal channels of policymaking to arise.

This is precisely how the likes of Rudy Giuliani and his associates have been able to insert themselves into the policymaking process. The high turnover within the key coordinating bodies such as the National Security Council and in managerial roles such as the White House chief of staff has enabled the rise of a parallel foreign policy.40 Those that have departed the administration have described the informal policy process led by Giuliani as having the effect of a hand grenade,41 while the tendency to appoint only ‘yes-men’ as a pathway to impeachment.42

Likewise, the unorthodox practices, such as governance by Twitter and the resulting ‘spontaneity’ in policy proclamation, has torn up the traditional diplomatic playbook and has left both the public administrators and foreign governments on the edge.43 Foreign leaders have realised that in order to extract economic and military benefits from the president, they ought to flatter and oblige him. The examples abound — from the parades44 in the president’s honour to even naming military bases after him.45

Thus, the compliments Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky paid to President Trump and his willingness to sign on to a presidential initiative to ramp up the anti-corruption probe which would focus on the Bidens in the infamous July 25 phone call can all be seen as a learned behaviour in trying to please President Trump. There is plenty of evidence that suggests the former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko was worried about President Trump’s support for Ukraine’s efforts to rollback Russia’s influence in the Donbas region.46 While there is still a contention over when exactly the new Ukrainian president learned about the nearly US$400m worth of military aid that President Trump ordered to be withheld, there is little doubt that Zelensky seized the opportunity to ingratiate himself with the US president.

The effects of the impeachment inquiry on foreign policy towards Ukraine and beyond

Given the observed pathologies in the Trump administration’s approach to foreign policy, the risk of abuse of power and serious wrongdoing was elevated from day one. As the impeachment process presses forward, the debate between those in favour of removing the president from office and those who support him will come back to presenting those deviations in a light that best serves each side. For the pro-removal camp, the case is building up around the premise that the intent of withholding the congressionally-approved funding for Ukraine was primarily motivated by extracting political benefits for the president as he enters the 2020 presidential race.

Those who support the president have trialled several lines of defence so far. From denying there has ever been any quid pro quo because the Ukrainian government was not aware of the withheld aid, to becoming laxer about this depiction and presenting it as the quintessential issue linkage in foreign policy negotiations.47 Then there are those who go back to the “unitary executive theory” arguing that by the virtue of being the chief of the executive branch, the president has almost absolute constitutional authority over the way its power is administered, particularly in the foreign policy domain. Moreover, that there was no wrongdoing as the president finally released the aid to Ukraine without there being an investigation into the Bidens. Finally, some of the arguments in defence of the president have veered into the absurd by suggesting that given the incoherence of the policy towards Ukraine, it is hard to see how any of its elements would have been effective and thereby incriminating.48

As a result of the impeachment process, there is no doubt the bandwidth of the legislative and executive branches to focus on pressing foreign policy matters will be affected. There have already been direct blows dealt to the US policy towards Ukraine as the role of the Special Envoy is dissolved and the US presence at the peace talks between Russia and Ukraine is diminished. The fear of Ukraine policy becoming politicised is also not to be discounted if the Democratic leadership in the Congress insists on the Ukrainian government’s cooperation in the impeachment inquiry, which will undoubtedly aggravate the White House. Ironically, this all seems to benefit Russia, since the very need for US military aid to Ukraine in the first place — Russia’s incursions into Ukraine — seems to fall out of the limelight.

Finally, the impeachment process is a signal to foreign leaders around the world about the perils of pursuing unconventional channels in dealing with the US government. As the 2020 presidential election edges closer, friends and foes alike can be expected to hedge their bets on who they might find residing at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue on 21 January 2021. The impeachment inquiry and the looming trial will factor into these calculations. If the process erodes presidential support, the White House might try to divert the public attention onto other issues. Again, the foreign policy front is where the president has the most manoeuvring space. There are speculations of various deals he might strike with foreign counterparts in China, North Korea and Iran and tout as major wins for the administration. At the same time, there are fears of escalating tensions and potential for initiation of diversionary conflicts, which could be intensified given the president’s weakened bargaining position. Absent a crystal ball, the only certainty is that the impeachment compounded with the 2020 election campaign spells a continuing foreign policy mess.

In contrived impeachment proceedings, Democrats try to influence the next election by accusing Trump of doing the same

Mia Love

Americans are right to be sceptical of the way Democrats have undertaken the presidential impeachment process so far. If those in the political centre are able to disassociate their dislike of President Donald Trump’s tweets or truculent personality traits from the current direction of impeachment proceedings, it becomes apparent that the complete lack of bipartisan support, transparency, selective release of information and absence of an actual crime point to a process that has been weaponised for political gain.

Americans are ill-served by a Congress that has essentially abandoned its lawmaking responsibilities to pursue a partisan objective that risks lowering the bar on impeachment to the extent that no future president will ever clear it.

Democrats began discussing and pursuing impeachment mere months after Donald Trump took office as the 45th president.49 It has severely damaged their cause in trying to convince the American people of its sudden urgency and importance more than two years later — and so close to another US presidential election.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi just nine months ago acknowledged the importance of a bipartisan proceeding. In a March 2019 interview for The Washington Post Magazine, Pelosi said: "Impeachment is so divisive to the country that unless there’s something so compelling and overwhelming and bipartisan, I don’t think we should go down that path because it divides the country. And he’s just not worth it.”50

Speaker Pelosi is currently failing the test she set herself and her colleagues. There is nothing bipartisan, overwhelming nor compelling about this latest effort to remove a Republican president.

What is so compelling and overwhelming and bipartisan that Democrats must now pursue impeachment? It is certainly not a bipartisan effort. The first official vote as part of the current impeachment investigation process was 232-196, with all Republicans voting no and two Democrats crossing party lines to vote against the resolution.51 That's an improvement over three previous impeachment resolution votes by the House. In December 2017, Republicans joined 126 Democrats who voted to reject a different impeachment resolution.52 Again in January 2018, a resolution was brought forward. This time 121 Democrats voted to table it. A third vote was held in July 2019 in which 137 Democrats and all Republicans rejected impeachment.53

Speaker Pelosi is currently failing the test she set herself and her colleagues. There is nothing bipartisan, overwhelming nor compelling about this latest effort to remove a Republican president.

At the time of writing, interviews have been conducted in secret, with only cherry-picked details strategically and selectively released to the public by the Chairman of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence Adam Schiff. This is the same Adam Schiff who promised Americans for two years that he had seen evidence of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia.54 Two years and almost US$40 million later, the Mueller Report provided no such evidence, and concluded that investigators were unable to charge the president with a crime.55

Speaker Pelosi bragged on polling day during the 2018 midterm elections: “When Democrats win — and we will win tonight — we will have a Congress that is open, transparent and accountable to the American people."56 But the impeachment process has been anything but open and accountable. Day after day, members of Congress emerge from the secure bunker with vastly different stories of what they saw and heard. After US Envoy Bill Taylor testified behind closed doors, Democrats released a damaging opening statement by Taylor. Democratic lawmakers called the testimony "damning".57

Meanwhile, Republican Lee Zeldin, who sits on the House Committee on Foreign Affairs and participated in the hearing, later offered a different take. “Much of his leaked opening statement collapsed, but Schiff keeps the public in the dark on that!” Zeldin tweeted.58 House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy told Fox News that Taylor's testimony was taken apart: "What I'm hearing, is that in 90 seconds, we had John Ratcliffe destroy Taylor's whole argument."59 McCarthy went on to say that "Adam Schiff won't let us talk about what happened. But what we're finding is that just his questioning in 90 seconds refuted everything of what Adam Schiff believes. There is no quid pro quo."

Now that the transcripts have been released — and after reading them myself — I find it difficult to disagree with my Republican colleagues on their assessment.60 How are the American people to navigate these two opposing narratives if the transcripts of the interviews are withheld, selectively published or if their release is delayed? This is hardly the transparent and accountable Congress Pelosi promised on midterm election night.

Thus far the allegations Democrats are using against President Trump are unflattering, but not unprecedented — and not likely illegal. Like President Barack Obama, whose administration pursued a politically convenient investigation against the Trump campaign in 2016, Donald Trump now stands accused of trying to pursue an investigation of 2020 Democratic candidate Joe Biden in the run-up to next year’s campaign. The Trump administration claims the same motivation as the Obama administration did: an attempt to clean up corruption.

If Democrats can't convince the American people they have evidence of a legitimate high crime or misdemeanor — not a contrived one, but an actual crime — the party risks being savaged in the 2020 elections.

A fair impeachment process would enable Republicans to pursue witnesses and testimony in defence of the president’s actions, including evidence or precedent that the Obama administration is guilty of similar conduct. Perhaps we'll see that in a potential Senate hearing, but currently House Democrats have stacked the deck to ensure only one side of the story is currently being told in that chamber of Congress.

Democrats won control of the US House of Representatives in 2018 by flipping centre-right districts like mine in Utah. Moderate candidates promised a "better deal for our democracy" focused on "better jobs, better wages, and a better future for all Americans". But just one year into the new Democratic House majority, the conversation has continued to focus on impeachment. Tackling policy and lawmaking is all but forgotten as Speaker Pelosi manages eight different committees investigating various allegations against President Trump. The House Intelligence Committee, formerly used to oversee national security threats in classified settings, has essentially abandoned its mission in favour of holding secret hearings in the secure basement underneath the US Capitol.

If Democrats can't convince the American people they have evidence of a legitimate high crime or misdemeanor — not a contrived one, but an actual crime — the party risks being savaged in the 2020 elections. This will particularly be so if the only allegation they can produce is one that wasn't considered a crime when President Obama did it during the previous administration.

By lowering the bar far enough to entrap President Trump, they risk subjecting the American people to never-ending impeachment proceedings as the losing party seeks to reverse the results of every future presidential election. This partisan and secretive proceeding lacks credibility. It should be unacceptable.

Yet with all of that said, the president has not done himself any favours. He makes it difficult for Republicans to support him. He continues his inappropriate and unpresidential intimidating tactics, he refuses to stop his Twitter rants, he continues to work in isolation, and he is not focused on the economy and his vision for the American people. He is his own worst enemy. His bullying tactics have widened the partisan divide and emboldened the enemies who hate the United States and want to see our country destroyed.

The Republican position of standing behind the president at all costs has put all of us in the position we are in today: All impeachment and no policymaking or governing. Congressional Republicans have refused to be a check and balance on the president and this has created a brash, emboldened, do what I want, when I want President. So here we are, deep in impeachment while the federal government will be running out of money.

Congress should get back to working for the people who elected them by aiding in the legislative solutions to problems like health care, immigration reform, curbing out of control government spending, executing a smooth and timely budget process, and passing a heavily bipartisan free trade agreement with Mexico and Canada.

The Politics of Impeachment on Congress, the Presidency, the American People and American Democracy

Bruce Wolpe

With apologies to Shakespeare:

To impeach, or not to impeach,

that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles.

Speaker of the House of Representative Nancy Pelosi is no Hamlet, and her cunning is far deeper than that of Shakespeare’s prince. And she knows how to take arms.

Impeachment dies in the House

President Trump is correct in his belief that since his election, many if not most Democratic voters, and likely a similar proportion of Democratic members of Congress, have wanted the president removed from office before the end of his term.

Why? In raw terms, Democrats in the House believe President Trump is unfit for office. A disgrace to the modern presidency. The presider of chaos in the White House and throughout his administration.61 Unstable. Redolent of extreme narcissism. A compulsive liar and bully. Vulgar and obscene. Exhibits contempt for the norms of American democracy.62 An existential threat to the country.63 A lover of authoritarian leaders. Hated around the world.64

The House of Representatives was on a course to impeachment throughout Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigations into the 2016 election. The expectation was that Mueller would show a criminal conspiracy between the Trump campaign — perhaps involving Trump himself — and the Russians to harm Hillary Clinton’s campaign and benefit Trump’s election. Second, that the firing of FBI director James Comey, and other actions taken by President Trump and his associates to derail the Mueller investigation, would result in a clear case of obstruction of justice.

President Trump is correct in his belief that since his election, many if not most Democratic voters, and likely a similar proportion of Democratic members of Congress, have wanted the president removed from office before the end of his term.

To the shock of Democrats in the House, Mueller could not establish a Trump-Russia conspiracy.65 And Mueller declined, because of guidelines regarding whether a sitting president could be indicted, to make a finding on whether President Trump had obstructed justice. Moreover, the special counsel did not make an affirmative statement that, had Trump been anyone other than the president and engaged in all the documented activities, he would have sought Trump’s indictment on obstruction of justice.

That impeachment effort of President Trump died when Mueller could not sufficiently address several challenges:

- While the obstruction of justice case was clear to many House Democrats, especially on the Judiciary Committee, Mueller’s reticence meant that case could not be demonstrated by the committee to the American people.

- The White House was very effective in stonewalling the testimony of those who could corroborate an impeachable offence, most especially Don McGahn, the White House counsel, who was named more than any other person in the Mueller report as being involved in the decisions and activities to impede the Mueller investigation. McGahn has still not testified; his subpoena and assertion of executive privilege have languished in court for months.

- As a result of these failings, there was no irresistible groundswell for impeachment in the Democratic caucus, much less in the county as a whole. By August 2019, after Mueller testified in the House, barely half the House Democrats had formally endorsed initiating an impeachment inquiry,66 and less than half the country felt the same way.67

By Pelosi’s own standards, the calls for impeachment fell short. In March 2019, she explained her view in an interview with the Washington Post:

“I’m not for impeachment. This is news. I’m going to give you some news right now because I haven’t said this to any press person before. But since you asked, and I’ve been thinking about this: Impeachment is so divisive to the country that unless there’s something so compelling and overwhelming and bipartisan, I don’t think we should go down that path, because it divides the country. And he’s just not worth it.”68

Three realities underpinned that judgement: The American people would not support impeachment. Secondly, If the House impeached, the Republican-dominated Senate would never convict. And finally, the political blowback could cripple the Democrats in 2020.

Impeachment was not on a fuse, but there were burning embers that kept it alive: the growing frustration that Trump’s stonewalling of inquiries by House committees of the White House and Executive Branch — the denial of testimony and documents, the lawsuits against congressional subpoenas, and the White House efforts to de-legitimise congressional oversight — was obstructing the ability of the House of Representatives to exercise its rights under the separation of powers enshrined in Article I of the Constitution.

Oversight is the bread and butter of Congress’ responsibilities under the Constitution. Despite there being no clear path forward to make Trump accountable to Congress after the Mueller hearings, Democratic members were coming to apprehend that Trump’s willful denial of their ability to do their jobs properly meant that a point of constitutional reckoning was becoming unavoidable.69 We will never know whether the House would ultimately have proceeded with impeachment on the grounds of obstruction of Congress on those grounds alone.

The impeachment fuse is once again lit

In his final round of testimony July 24 before the House Intelligence Committee, Mueller warned about the grave threat to American democracy from foreign interference in America’s elections. The Russians, he said, “Are doing it as we sit here, and they expect to do it during the next campaign… I have seen a number of challenges to our democracy. The Russian government’s effort to interfere in our election is among the most serious.”70

The next day, July 25, President Trump spoke with President Zelensky of Ukraine. The president asked for a “favour”: that Ukraine interfere in the US election by investigating Trump’s principal political opponent, Joe Biden as well as his son, Hunter Biden.71

One month later, a whistleblower report on that phone call became public detailing collated evidence that the president had made aid to Ukraine conditional on such an investigation.

On September 23, seven freshman Democrats, all elected in districts that Trump carried in 2016, joined in an op-ed demanding that an impeachment inquiry on Trump and Ukraine go forward. Their duty to uphold the Constitution demanded, they wrote, that “Congress must determine whether the president was indeed willing to use his power and withhold security assistance funds to persuade a foreign country to assist him in an upcoming election”.72

It was this shift in sentiment and the imperative driving these freshmen that convinced Speaker Pelosi that impeachment had to be addressed and trumped the conventional wisdom that impeachment would badly backfire on Democrats.

Indeed, given the clarity and relative simplicity of the Ukraine case — as opposed to the complexity of the Mueller investigations — there was a steady shift in public opinion so that, by the time the House voted on October 31 to begin formal impeachment proceedings, several polls had already shown a majority of the country in favour of these proceedings, with a bare majority in favour of Trump’s removal from office.73

The politics of impeachment

Congress

Impeachment is as intense a political exercise as exists under the Constitution as it involves removing a president from office. The hyper-partisan vote in the House to formally commence proceedings shows that this impeachment will be thoroughly marked by partisan division. Only two Democrats voting no joined all other Republicans in the 232-196 vote in favour of impeachment proceedings. It would likely take the equivalent of the Watergate tapes — a taped conversation on the phone or in the Oval Office whereby President Trump is heard saying that he wants to destroy Biden and wants to use Ukraine to do it — to pry loose some House Republicans into voting for an article of impeachment.

The hyper-partisan vote in the House to formally commence proceedings shows that this impeachment will be thoroughly marked by partisan division.

In the House, only one Democrat elected in the 2019 midterm wave voted with the Republicans to oppose the inquiry (the other was a near-30-year veteran in a solidly Trump district). This means that those Democrats on the most vulnerable political ground believed they could weather any blowback that the case for impeachment would strengthen as the House proceedings continued, and that they could face re-election with confidence.

This suggests that the House will remain Democratic even with Trump’s acquittal in the Senate — even if a few more Democrats ultimately vote against specific articles of impeachment.

The partisan character of the House vote will frame the atmosphere in the Senate as a trial gets underway.

In the Senate, most attention has been focused on vulnerable Republicans Susan Collins of Maine and Cory Gardner of Colorado, among others up for re-election in 2020. But if there is pro-Trump backlash from impeachment, it could envelop Democrats Doug Jones in Alabama and Gary Peters in Michigan — both states Trump carried in 2016.

This suggests impeachment will not drive a change in control of the Senate.

Trump’s presidency

No president has been under impeachment while running for re-election, much less facing a Senate trial 10 months before an election. In raw political terms, impeachment involves weakness and ridicule, and is an exercise in humiliation by virtue of the high degree of exposure of official actions to public scrutiny.74

The conventional wisdom, flowing from what happened in the immediate aftermath of the impeachment and acquittal of President Bill Clinton in 1998-99, was that the Republicans, who orchestrated that impeachment, suffered politically — and that therefore the Democrats in 2020 will suffer the same fate of “electoral retribution”.

On the surface, it looked like the Clinton impeachment backfired on the Republicans.

Indeed, in 1998, with impeachment well underway, the Democrats gained five seats. The Republican Speaker, Newt Gingrich, resigned his post in part to the failure of impeachment. The Senate, though, remained unchanged.

What is underappreciated in this conventional wisdom is that the Republicans, even after impeaching Clinton, and even after Clinton was acquitted in the Senate, could still keep control of both the House and Senate in the midterms, and take back the presidency in 2000, with George W. Bush beating Vice President Al Gore. Additionally they then went on to hold the White House for eight years.

Impeachment, in other words, ultimately strengthened the party that sought to take down the president — and left the Democrats weaker, because Clinton was damaged. As David Leonhardt wrote in October 2019:

“Ultimately, impeachment may well hurt some Democrats from Trump-friendly districts, much as it hurt several Republicans 20 years ago. But it is also very likely to damage Trump.”75

The most important political question for 2020 to assess after impeachment is concluded: Is President Trump stronger or weaker?

The American people

When Richard Nixon resigned and Gerald Ford took the oath of office, the new president said that day: “My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over. Our Constitution works. Our great Republic is a government of laws, and not of men.”76

It is hard to see how, after a presidency marked by Trump’s wilful division of the country, and such a bitterly partisan exercise — no matter how it is resolved — that the country will come together in unity and put its raw divisions aside.

America’s democracy

The prognosis, therefore, is for continued retribution. The strains on the democratic institutions of government — which today are near the breaking point — will take years to heal under even the most enlightened and courageous leadership. The United States’ political pathology has resulted in two of the last four presidents facing impeachment — the last resort of the representatives of the people under the Constitution. What should be the rarest, most singular of exceptions is now a part of the normal conduct of political discourse.

With apologies to George Santayana: We appear condemned to repeat the history we remember.