On 8 November, Americans will cast their vote to decide who will represent them in Congress and in various roles at the state and local levels.

Unlike Australia, where state and federal elections run on different timelines, the United States aligns much of its state and federal votes for the second Tuesday in November every two years. Since a presidential term is four years, but all members of the House of Representatives (who serve two-year terms) and a third of all Senators (who serve six-year terms) face an election every two years, the off-peak cycle is called the midterm election because it happens in the middle of the presidential term. Votes are cast for local, state and federal government positions, but the exact makeup of each local ballot varies based on staggered term lengths and where they fall in the cycle.

As explained below, even though the president is not on the ballot, the president factors heavily into the midterms. These elections are widely perceived as a performance review – a referendum on the president and the party in power. Once the midterms are finished, attention then pivots to the next presidential election.

Who is up for election?

The national component of the midterms (the vote for Congress) often garners the most attention. The entire Congress is made up of 535 members in total (100 in the Senate, 435 in the House). Alongside the congressional elections, several states will hold elections for key state-level positions in November 2022.

Which US states are holding elections in November 2022?

|

Position |

Term length |

Number in 2022 midterms |

States with elections in 2022 |

|

Senator |

Six years |

35 (One third every two years) |

Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin |

|

Representative |

Two years |

435 |

All |

|

Governor |

Four years (Two years in New Hampshire and Vermont) |

36 |

Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Wisconsin, Wyoming |

The House of Representatives

Each US state is divided into congressional districts that elect members to the House of Representatives. There are 435 districts and representatives across the United States. Each state has at least one representative, with additional seats allocated proportionally based on population. California has the most representatives (52), followed by Texas (38). Delaware, Vermont, Wyoming, and North and South Dakota have the least, with only one representative each. All 435 seats in the House of Representatives are up for re-election in November because members only serve two-year terms.

The Senate

The Senate is the upper chamber of Congress. Each US state, irrespective of its size, is represented by two senators who serve staggered six-year terms. Around a third of the 100 Senate seats are up for election every two years. In November 2022, 35 senators are up for re-election. As well as the standard 34 seats in this cycle there is a special election to fill an additional seat made vacant by Senator Jim Inhofe (R-OK), who announced his retirement earlier this year.

State elections

In some states, a handful of other candidates are vying for state-level positions, including governors (the equivalent of premiers or chief ministers in Australia), state senators and representatives, and local public offices including mayors. This cycle, 36 states will hold elections for their governors, 30 states will hold elections for their attorneys general, and 27 will vote for secretary of state positions. While these roles rarely make headlines in Australia, recent developments impacting a number of key state-regulated civil liberties including abortion rights, gun rights and electoral reforms, mean these state-level races are more closely watched in 2022.

How is this different to the primary elections?

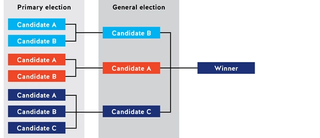

Unlike Australia’s system, where party candidates are chosen in a preselection process by party members, typically American voters nominate candidates to represent their party in primary elections held in advance of the November general election. In the seven months of primary contests running across states since March this year, Americans (either registered party members for ‘closed primaries’ or any voter, including non-Party members, in ‘open primaries’) determined who will represent each major party in the midterms as their party’s nominee. On 8 November, the Republican and Democratic candidates who won their respective primary elections will face off in a contest for congressional seats and state-level appointments.

Why are the midterms important for US politics?

The midterms are an opportunity for voters to shift the balance of power in Congress, the main legislative body in the United States. While the role of the president is not up for election, the degree to which Congress aligns with or diverges from the priorities and preferences of the president will significantly impact how the president can govern. The president does not have the power to unilaterally pass Congressional legislation – only the power to sign bills into law or veto bills passed through Congress.

While the role of the president is not up for election, the degree to which Congress aligns with or diverges from the priorities and preferences of the president will significantly impact how the president can govern.

Without a supportive Congress to pass their desired legislation, presidents tend to shift their focus after midterm elections to powers and actions that do not require congressional approval, particularly foreign policy. For example, after a sweeping midterm election victory that saw the Republican Party take control of both houses of Congress in 2014, Democratic President Obama turned his attention to the “Pivot to Asia” and advance a trade partnership among Indo-Pacific partners, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

Under circumstances where the legislative chambers of Congress and the president’s priorities are misaligned, US presidents tend to lean more heavily on executive powers, such as executive orders, to govern. Executive orders create laws to be enacted by federal agencies without the approval of the US Congress, but they are still subject to judicial review and can be overturned by future presidents. For example, in October 2015 during his second term and with climate policy stagnating in a Republican-led Congress, President Obama announced his Clean Power Plan to expand the ability of the Environmental Protection Agency – a federal agency – to regulate states’ carbon emissions. Yet, the plan was never enacted as the ruling faced court proceedings in 2016 and was later overturned in an executive order by President Donald Trump in 2017. So, while they might seem like the “last word,” executive orders aren’t necessarily a shortcut to circumventing a gridlocked Congress.

In addition to lawmaking, Congress has several other important expressed powers, most notably ‘the power of the purse’, the regulation of commerce, the power to declare war, and control of investigative bodies and executive branch appointments. Therefore, the party and the type of candidates a party has representing them within the US House and Senate may alter the issues and policies congressional leaders consider to be important to finance or to investigate.

Which party is going to win control of the House of Representatives?

To achieve a majority in the House, a party must hold 218 seats. Currently, 221 seats in the US House of Representatives are held by those who caucus with Democrats, giving President Biden’s party a narrow majority. Republicans only need a net gain of five seats to win a majority in the House.

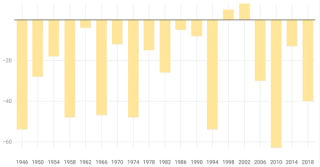

Long-term trends show the president’s party typically loses seats in the midterm elections. Since the Second World War, the president’s party has lost an average of 26 seats each midterm election cycle and even greater numbers where the president’s approval rating is below 50 per cent or the economy is performing poorly. In the case of President Biden, his approval rating is around 43 per cent while inflation has hovered above 8.5 per cent in a 40-year record for most of 2022.

Net House seat change for president's party in midterms, 1946-2018

Which party is going to control the Senate?

Unlike the House, not every Senate seat is up for re-election this November because Senators are elected on a staggered six-year cycle. There are 35 seats up for re-election in November – 14 Democrats and 21 Republicans. The Senate is currently split 50-50 but, because Vice President Kamala Harris holds the tie-breaking 51st vote, Democrats have controlled the Senate for the first two years of the Biden administration. Nonetheless, significant aspects of the Democratic Party’s legislative ambitions were still muted by Senate rules, most notably the filibuster, which requires 60 votes for cloture and for a bill to come to a vote on the Senate floor. This demonstrates that while having a majority of seats in the Senate is beneficial, the actual operations of the Senate often require significant bipartisan negotiation and support to pass legislation. In other words, passing legislation requires more than just the support of the 50 senators. To really control the legislative agenda in the Senate demands a super-majority of 60 seats.

What happens if Republicans win the House and/or the Senate?

If Republicans win a majority in the House or Senate, there will be both structural and legislative changes. Most notably, losing his party’s majority in the House will make winning support for President Biden’s policies and agenda far less certain and less likely.

Should Republicans win the House, Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) will be replaced as Speaker of the House by a Republican representative. The Speaker of the House is a powerful and influential role. In addition to representing the party’s leadership, they are second-in-line (after the vice president) to assume presidential office, and they act as the administrative head of the largest legislative chamber in the US Congress. This enables them to determine when issues are brought to the floor for voting and to assign House members to the chamber’s various committees, which themselves have the power to conduct reviews and investigations on a range of legislative portfolios.

Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), the House Minority Leader, is currently considered the frontrunner to take up the Speaker's gavel should Republicans gain a majority in the House.

Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), the House Minority Leader, is currently considered the frontrunner to take up the gavel should Republicans gain the majority. But his ascendance is far from certain as he will first he will need a majority of votes from the House floor at the start of the new Congress in 2023.

In terms of Republican policy priorities, the Republican agenda for the House was revealed by Kevin McCarthy in a four-part ‘Commitment to America’ on 19 September. This formal statement follows a similar campaign logic to House Republicans’ 1994 ‘Contract with America’, which was issued just six weeks before a notable “Republican Revolution” at the midterm elections that saw the party gain 54 seats in the previously Democratic-controlled House during the Clinton administration. The ‘Commitment to America’ provides three insights into what a Republican-controlled House policy agenda might look like, including:

- reduced support for government spending on the Biden administration’s Build Back Better initiatives,

- a suspension on the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy projects and

- a greater emphasis on domestic manufacturing and securing supply chains.

Determining the policy direction for a Republican-controlled Senate is not as clear-cut. With fewer members than the House, much of the direction and temperature of the Republican Party in the Senate depends on the personalities and backgrounds of the senators themselves. Several Republican Senate hopefuls, including candidates in competitive races in Pennsylvania, Georgia, Ohio and Arizona, have not held office before and do not have voting records to indicate their congressional priorities or political playbook.

The Senate’s more deliberative ‘advise and consent’ functions also mean that, as opposed to a legislative agenda, the ideological positions of Senators can weigh into critical institutional decisions like the approval of Cabinet ministers, federal judges and ambassadors can often have a legacy that outlives the service terms of senators. Take, for example, the near-party line appointment of conservative-leaning Supreme Court justices Neil Gorsuch (54-45), Brett Kavanaugh (50-48) and Amy Coney Barrett (52-48) during the Republican-majority Senate under the Trump presidency.

Similarly, the House's investigative abilities under a Republican government may be used in new or different ways, casting doubt over some key ongoing investigations such as the House Inquiry into the January 6 attack on the Capitol and raising the possibility of new impeachments.

What’s happening at the state level?

Forty-six states will have elections on 8 November 2022 for a range of positions in state legislative chambers and other state-level positions. Thirty-six states and three territories will host gubernatorial elections to elect state governors (like an Australian state premier). Other positions on the ballot include attorney general, secretary of state and state treasurer.

These state-level races are more closely watched in 2022 due to the prominence of public concern about violent crime and voting rights as well as recent Supreme Court rulings that handed abortion rights to the states, with some even putting abortion issues directly on the ballot.

State and local elections have historically lower turnout than presidential elections, yet state-level decisions can have major impacts. The powers and responsibilities of these positions are more visible since the coronavirus pandemic, with governors playing an outsized role in determining health policies since 2020. The 2022 midterms will see several governors face their first re-election since the pandemic.

These state-level races are also more closely watched in 2022 due to the prominence of public concern about violent crime and voting rights as well as recent Supreme Court rulings that handed abortion rights to the states, with some even putting abortion issues directly on the ballot. The role of secretary of state in particular has gained new focus because of their responsibility in many states for the oversight of electoral processes, which includes the certification of federal election results. Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger rose to national attention after the 2020 election when he famously refused to “find 11,780 votes” for former President Trump. He is on the ballot in Georgia, with an 11-point lead over his opponent.

What’s new in 2022?

Redistricting

Every 10 years following the completion of the national census, each US state decides whether or not to redraw its political lines to create new congressional districts in a process known as ‘redistricting’. Redistricting is important because the results shape the balance of power in Congress for the next decade. It also helps election watchers determine the partisan lean, and therefore the likely outcome, of competitive elections. The conclusion of this once-a-decade process finished in 2022 so the upcoming midterm elections will see these new districts in play for the first time.

Redistricting is intended to keep elections fair by ensuring each legislative district represents roughly equal populations. It is why densely populated states, like California, have 52 districts and less populated states, like Montana only have three. Unlike in Australia, where dividing up legislative districts (electorates) is the domain of an independent electoral commission, in most US states redistricting is primarily overseen by the state legislature though a handful of states delegate the responsibility to groups of elected officials and independent commissions.

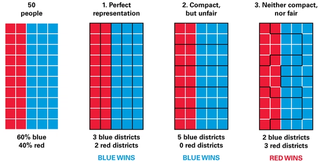

This raises the issue of partisan gerrymandering – the manipulation of electoral maps to benefit one political party. Gerrymandering can simply be thought of as politicians picking their voters, rather than voters picking their politicians. For example, an incumbent party may try to minimise the representation of the challenging party by redrawing maps that split the representation of the challenger’s voters into different districts and decrease their chance of election.

Gerrymandering: drawing different maps for electoral districts produces different outcomes

Some state’s district maps are being challenged as possible partisan gerrymanders, with court cases to be resolved after the midterms. For example, Alabama’s newly drawn map will be used for the November elections, but the state will soon face the US Supreme Court over an alleged violation of the Voting Rights Act (1965) as only one of the state’s seven districts has a Black majority despite having a Black population of almost 30 per cent.

Referendums

This year, six states will include a referendum on abortion access on their ballots following the US Supreme Court’s June 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson decision that overturned federal constitutional abortion access and handed individual states the authority to pass their own legislation on abortion.

In Kansas – the first state to put abortion access on the ballot at their midterms primary race in August 2022 – voters overwhelmingly, and unexpectedly, rejected proposed restrictions on abortion access in their state. California, Kentucky, Montana, Michigan and Vermont will feature an abortion question on their ballots in November. These questions are designed to either add protections, enshrine abortion access in the states’ constitutions and prevent future restrictions on abortion access – as is the case in California, Michigan and Vermont – or to clarify the legal right for states to further restrict abortion access like with Kentucky. Montana’s referendum would ask voters to weigh in on the Montana Born-Alive Infant Protection Act, which would require healthcare providers to administer care to babies deemed “alive” at any stage of pregnancy.

Why do the midterms matter to Australia?

The US midterm elections will alter the composition and policy focus of the main legislative bodies in the United States for at least the next two years. In doing so, Congress’ alignment or misalignment with President Biden’s agenda, and the priorities of new members of Congress will determine the scope and opportunity for cooperation between the United States and Australia on shared objectives.

Since Biden’s election, the Democrats’ triple hold on the House, the Senate and the White House saw a strong legislative focus for the US Government, with a limited window of time to pass wanted reforms with their majorities. Should the president be less able to pass wanted programs through Congress by losing his party’s hold on both chambers, it is feasible to suggest that US foreign policy will receive greater executive attention. At the same time, this result would make it more difficult to work with Congress to create lasting foreign policies and may see the president rely more heavily on executive actions which risk being discontinued with the next president.

Congress’ alignment or misalignment with President Biden’s agenda, and the priorities of new members of Congress will determine the scope and opportunity for cooperation between the United States and Australia on shared objectives.

The make-up and agenda of congressional committees – several of which have particularly powerful abilities to enable or constrain the US foreign policy agenda – change depending on which party wins a majority in the midterm elections. While most committees are bipartisan and feature members chosen by their party leaders, the majority party decides who chairs the committees and therefore what the agenda of the committee will be. Such a change can impact the resources, openness and direction of US policies on issues like defence spending, trade agreements and resourcing competition with China.

Committees for Australia, in particular, to watch include:

- The House and Senate Armed Services Committees oversee and fund the Department of Defense and US Armed Forces;

- The House and Senate Foreign Affairs Committees take care of the foreign affairs of the United States, such as foreign assistance, foreign policy, treaties and national security developments;

- The House and Senate Appropriations Committees are responsible for the budget and spending of the US government;

- The House Energy and Commerce Committee has the broadest jurisdiction of any Congressional committee and oversees a number of policies of Australian interest like renewable energy, foreign commerce and cybersecurity; and

- The Committee on Ways and Means negotiates major trade agreements and tax cuts.

Regardless of the outcome, the midterm elections represent an important temperature check on the priorities and interests of the American people, how they engage with their political institutions and the future of Australia’s closest ally. From AUKUS and defence cooperation to technology and trade, it remains essential for Australia to continue engaging diverse Washington actors on areas of Australia’s critical interests – particularly the Congressional members and committees who determine the legislative and budgetary constraints for such endeavours.