This is the second in Jim Orchard's three-part series on the formulation of Joe Biden’s climate change agenda. Part one and part three are also available.

On 15 March, during what turned out to be the final debate of the Democratic primary, Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders went back and forth on fracking. Biden got in the final line: “No more... no new fracking”.

This was interpreted to mean that, if elected, Joe Biden would ban fracking. This would be a big deal and a major victory for progressives who were hoping by staying in the race, Bernie Sanders could push Biden further to the left on a number of key issues. With more debates, rallies and primaries to come, Sanders supporters were hoping to get more out of Biden — more money for renewables, a faster roll-out of electric vehicles and, most importantly for some, a stronger commitment to the full Green New Deal vision.

During what turned out to be the final debate of the Democratic primary, Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders went back and forth on fracking. Biden got in the final line: “No more... no new fracking”.

So, what happened? Within days, the Biden camp clarified the comment explaining the candidate was only talking about banning new fracking permits on federal lands. A few days later COVID-19 effectively put an end to a Bernie Sanders primary squeeze play on climate change and the Green New Deal.

This now seems like an eternity ago and the fact Joe Biden was so easily rattled into confusing his own position on fracking was lost in the maelstrom of the pandemic. The quote will not be lost forever — expect to hear it again as a sound bite in Republican election material.

Fracking is a big deal

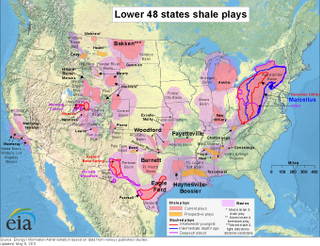

The presumptive Democratic nominee’s slip on fracking is probably not a big deal in and of itself. After all, Biden is known for making a few verbal missteps. However, fracking is a big deal and could be a big deal for the election. As shown in the map below, fracking’s physical footprint covers a significant part of the United States. Once the province of speculative junior drillers, fracking — the pumping of high-pressure water into rock formations to release oil and gas — is now employed by most major oil and gas corporations and is the United States’ dominant fossil fuel extraction technology. Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, collectively known as fracking, for coal seam gas is a uniquely American development. Not only was the technique perfected in the United States but globally the best fracking reserves appear to be in the United States as well. The US Chamber of Commerce claims fracking supports 15 million jobs and supporters say it has made the nation energy self-sufficient and boosted local manufacturing in a number of key states.

Opposition to fracking is primarily based on the argument it pushes the world closer to a catastrophic climate outcome. The involvement of major oil and gas companies adds to the depth of opposition, being emblematic of the profit-driven disregard for environmental damage and the stranglehold the fossil fuel industry has over government at all levels.

From the perspective of not just the local economy and the electoral college but perhaps also from the viewpoint of future industrial hegemony, Pennsylvania and Ohio are at ground zero. Both are among a handful of states (including Michigan, Wisconsin and Florida) on which the 2020 election will likely be won or lost. They also lie over three major shale formations, including the massive Marcellus deposit, one of the largest and most productive fracking regions in the country. The size of the Marcellus fracking operations means more than just lots of local jobs, it also means significant lobbying power and funding for pro-fracking candidates. Significantly, fracking in Pennsylvania and Ohio mostly takes place on private land, outside the scope of a Biden position focussed only on federal land.

What would a change to Biden’s position on fracking achieve?

Joe Biden’s current position is a compromise. Federal land in states like Colorado, New Mexico, North Dakota and Wyoming are responsible for a relatively modest share of the nation’s oil and gas production — 26 per cent of oil and 13 per cent of gas based on Department of the Interior data. While important, it is also fair to surmise these states are far less likely to play a pivotal role in the presidential contest than swing states further east.

Despite the early end to the primary process, Joe Biden is still facing pressure from progressives wanting more. Soft on fracking means being soft on the most egregious sector of US big business.

Unlike some of his primary opponents, Biden has opted to avoid a major battle over fracking. He is on the record as saying, “you can’t ban fracking right now; you’ve got to transition away from it.” This reflects a view that the nation still needs and values cheap oil and gas (as well as the jobs and economic activity which come with fracking). It also implies Biden feels renewables are not yet ready to supply the lion’s share of US energy needs. This is a pretty standard centrist position supported by facts such as those provided by the Department of Energy estimating oil and gas supplies 80 per cent of total US energy needs, compared with only 11 per cent coming from renewables (including hydroelectricity).

Democratic pragmatists will be happy Biden has escaped having Sanders publicly pressure him on topics like fracking. The debates which never happened could have seen Sanders arguing that he was committed to ending the nation’s reliance on oil and gas and striking a blow for reduced corporation influence on government but Biden was giving the industry a free pass in places like Pennsylvania and Ohio to make massive profits while damaging the environment.

Despite the early end to the primary process, Joe Biden is still facing pressure from progressives wanting more. Soft on fracking means being soft on the most egregious sector of US big business. The fossil fuel industry stands accused by progressive Democrats of forcing higher levels of pollution and a cycle of poverty and despair onto the residents living in the shadow of their operations. If this was not bad enough, they then funded sophisticated climate disinformation campaigns which held back action on decarbonisation for decades. Activists who want disadvantaged communities to be compensated by the industries which made them suffer have coalesced around a vision captured in the Green New Deal. These are the voters who are not happy with Biden’s pragmatic stance on fracking and want him to go further.

.jpg?rect=0,80,3000,1989&fp-x=0.5&fp-y=0.44772296905517583&w=320&h=212&fit=crop&crop=focalpoint&auto=format)