Key points

- The AT&T-Time Warner merger raises important questions about what a competitive market looks like on the ‘free and open internet’.

- Repealing net neutrality was a signature goal of Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chairman Ajit Pai following his appointment in early 2017, but whether the FCC has the authority to rule on the issue is an ongoing question. The issue goes before the DC Circuit court for oral arguments in February 2019.

- As more Australians get their content via online streaming services and are more dependent than ever before on the ‘network economy’, this area may invite greater scrutiny by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

Explainer: What is the State of the Union address?

In the world wide web today, not all data is created equal.

Net neutrality, according to its proponents, is the great equaliser: the principle that prevents Internet service providers (ISPs) from intervening – usually by offering paid ‘fast lanes’ – in how online content is delivered to users. In the absence of legal provisions for net neutrality, ISPs are the king-makers; they can set the pricing and determine which types of internet traffic are given priority. The implications of this for competition are enormous in light of AT&T and Time Warner’s vertical merger.

What’s happening in the United States with net neutrality?

Among the supporters of net neutrality regulations, freedom of speech proponents – many of whom are typically found on the right of American politics – have found common cause with anti-big business warriors on the left who are concerned about the growing monopoly power of telcos in the data-driven age. Net neutrality also has broad bipartisan support in the court of public opinion, with 83 per cent of voters in favour across both sides of the aisle. On the other hand, it has split the business community between supporters in Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google (FANG)1 world and opponents on the ISP and cable network side.

Although it's been a hot topic in recent years, net neutrality is far from a new concept in the United States. The term in its present iteration was coined by Columbia Law School Professor Tim Wu in 2002, but the intersection between network neutrality and competition has been part of the public narrative since the mid-nineteenth century.

The Postal Act of 1845 first articulated the framework for a national communications system, premised on a federal government monopoly over provision of the service and non-discrimination on content. Designating the US Postal Service as a 'common carrier' set an important precedent for how telcos are regulated today.

President Trump’s appointed FCC Chairman Ajit Pai repealed Obama-era net neutrality regulations in December 2017 on the basis that they crippled innovation and stymied the rollout of cable broadband.

Net neutrality legislation in its contemporary form was introduced under the Obama administration in 2015. Under Title II of the Communications Act, the Open Internet Order stated that cable ISPs would be treated as public utility providers or common carriers, rather than information providers. This reclassification obliged broadband companies to provide a higher threshold of service and subjected them to more onerous regulation. There is a public opinion dimension to this as well: as the public becomes more dependent on services provided by internet giants, and as the market structure increasingly resembles a monopoly, there is more pressure to regulate these companies as public utilities.

President Trump’s appointed FCC Chairman Ajit Pai repealed Obama-era net neutrality regulations in December 2017 on the basis that they crippled innovation and stymied the rollout of cable broadband. However, this move provoked around half of all US states to take steps towards legislating independently to enforce net neutrality in their state. California’s State Assembly passed a bill in August ushering in the toughest net neutrality regulations in the country. In practice, because of the networked nature of Internet traffic and the costs of compliance, the state that implements the highest regulatory hurdle for ISPs will set the standard for net neutrality regulations across the country. The Trump administration has mounted a legal challenge to state-based regulations on net neutrality, setting the stage for a fierce contest in 2019 over whether federal authority pre-empts states’ regulatory powers.

Who wins and who loses?

The ISPs

As the Internet age kicked into gear, consumers increasingly cut the cord with cable television and made the leap to streaming subscriptions, driving cable companies like Comcast to reinvent themselves as ISPs.

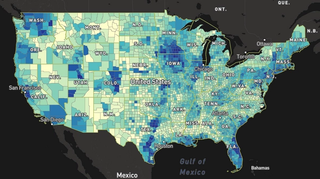

A major reason why net neutrality is so contentious is because of the market concentration of ISPs. In many parts of the United States, there is only one provider that services the region.

The Australian market is similarly concentrated, with three ISPs controlling over 80 per cent of the NBN market. What’s more, a report from Deloitte found that in Australia, 21 per cent of subscribers to subscription video on demand (SVOD) and music streaming services do so via a telco internet or mobile package. In an environment without net neutrality, the lack of competition means that ISPs have overwhelming power to dictate not just pricing but content prioritisation. This has important implications for innovation.

The debate over the consequences for innovation harks back to the antitrust arguments put forward at the dawn of the Internet age. On one hand, SMEs would argue anti-competitive behaviour by network companies deters innovation. On the other hand, ISPs would counter that network externalities actually encourage investment in innovation, by guaranteeing more durable monopolies to those that win the innovation gamble.

The potential gains to cable ISPs – and the antitrust issues that follow – are magnified when the company is both the content producer and the broadband provider, as is the case with AT&T and WarnerMedia. Net neutrality regulations are significant because they could discourage schemes such as zero-rating, which waives data charges against the user’s monthly cap for the provider’s preferred content (a practice that is common in Australia).

The content providers

Content providers are caught in the crosshairs of First Amendment claims to freedom of speech and the rights of private property owners; in this case, companies that control broadband spectrum. Meanwhile, small-to-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and entrepreneurs face steeper barriers to entry without net neutrality regulations in place, as they – unlike the major streaming services like Netflix – can be priced out of the market for internet ‘fast lanes’ or paid prioritisation deals with ISPs.

The impact of this is especially acute in businesses for which higher broadband speeds and low latency are paramount, such as streaming and gaming companies. In 2018 the US$30.4bn industry’s peak body, the Entertainment Software Association (ESA), followed the Internet Association (representing the FANG companies and others) in filing to oppose the FCC’s repeal of net neutrality.2 In the absence of net neutrality, Australian SMEs hoping to deliver online content in the United States may face barriers to entry and stiff competition from peers that have partnered with an American ISP.

The consumers

The concept and its implications for Internet users was popularised by John Oliver in July 2017. Oliver – along with consumer advocacy groups – makes the case that in a world where net neutrality is not guaranteed, fees charged by ISPs to Internet content providers will inevitably be passed on to consumers, or else crowd out content altogether. At a regional level, most US consumers have little choice when it comes to broadband providers, and net neutrality’s supporters argue that repealing the legislation only augments ISPs’ monopoly power. Nonetheless, in August 2018 a US appeals court upheld the FCC’s ruling that broadband markets can be deemed competitive even with only one ISP servicing that market.

One assertion made by the FCC’s Chairman Ajit Pai in favour of repealing net neutrality rules was that the regulations caused investment in high-speed broadband networks to decline: “When there’s less investment, that means fewer next-generation networks are built. That means less competition. And that means more Americans are left on the wrong side of the digital divide.”

Across the Pacific, the Australian government’s commitment to funding the NBN and supporting the rollout of a 5G network means Australia is more or less insulated from any projected downturn in investment as a result of introducing net neutrality laws. In the 15-year period to 2013, Australia invested more per capita in telecommunications capital than the United States. And with the increasing popularity of streaming services, Telstra’s new investments in subsea cable infrastructure suggest this stream of capital expenditure shows no sign of slowing down.

The regulators

The issue has the potential to put US government agencies at odds with one another. Already, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) publicly denounced the FCC’s repeal of net neutrality laws, indicating that the decision opens the door for anti-competitive practices by large broadband ISPs.

Yet even the FCC’s authority to rule on net neutrality is hotly contested. A landmark Supreme Court decision in the Brand X case (2005) empowered the FCC’s interpretation of the law regulating cable ISPs. The issue is making its way through the courts yet again, with Ajit Pai’s FCC telling the DC Circuit Court of Appeals the agency never had authority to rule on net neutrality to begin with.

The FCC also justified rescinding net neutrality on the grounds that doing so would spur internet innovation and deliver benefits to consumers.

The FCC also justified rescinding net neutrality on the grounds that doing so would spur internet innovation and deliver benefits to consumers. Meanwhile, the Department of Justice has upheld a relentless campaign of appeals against AT&T’s US$85 billion acquisition of Time Warner since the deal first became public in October 2016.

Why does this matter? Because if the DOJ based its legal argument on the premise that the merger could enable AT&T to prioritise Time Warner content above internet traffic from rival streaming content providers, it would be directly undermining the decision of the FCC to repeal net neutrality guarantees in Title II.

How does this compare to Australia, and what are the implications?

Australia’s competition watchdog, the ACCC, holds the power here, and has shown considerable willingness to wield that power over tech giants in the name of consumer protection in recent years. While some Australian content providers have made deals with major carriers to deliver unmetered access to their sites, Australia and the United States have a fundamentally different market structure for telco and subscription television services. This – as well as lower barriers to consumers switching between ISPs – means there is less incentive to engage in paid prioritisation that would prompt calls for net neutrality regulations in Australia.

However, the absence of net neutrality rules in Australia opens the door for ISPs and established content providers to set up exclusive preferencing arrangements, as Netflix and iiNet announced in 2015. This may be a harbinger of more to come. In the short-term, this could mean smaller players in the digital content wars are crowded out of the market. In the longer-term, as Australian audiences use more sophisticated streaming content direct from the United States, low latency delivery will be increasingly important. It may only be a matter of time before the pendulum shifts towards net neutrality in Australia, as consumers demand guaranteed choice and quality of service.