Executive summary

The balance of military power in the Indian Ocean is on the cusp of shifting. China is rapidly expanding its naval capacity and preparing for a larger naval presence in the Indian Ocean. Regardless of its long-term interests, the growth of Chinese submarine capability will give it the ability to exercise sea denial in coming years. This will pose an unprecedented strategic challenge for India and its partners such as Australia and the United States, which all seek the ability to exercise some form of sea control in the Indian Ocean.

At the same time, early evidence suggests that India has deprioritised investments in naval capability in favour of ground and air capabilities since the beginning of a border crisis with China in 2020. India is not keeping pace with its own earlier rates of naval capability development, let alone accelerating to keep pace with the impending growth of Chinese power in the Indian Ocean.

To manage this emerging risk, India and its partners should focus on deepening cooperation in anti-submarine warfare and undersea warfare. Such cooperation already occurs, but it remains episodic and limited in scope. Closer cooperation could take at least 3 forms:

- More routine and possibly even automated sharing of data on undersea domain awareness. This sharing could be calibrated in multiple dimensions — data from different sensors can be treated with different levels of sensitivity and shared with different partners.

- Coordination of naval operations, so that Chinese submarines would be less able to exploit gaps and seams between different countries’ surveillance capabilities. A hypothetical ‘Combined Anti-Submarine Warfare Operations Center’ could serve as a ready-made clearing house for situational awareness and coordination, in accordance with partners’ risk acceptance at any given time.

- Co-development of new technologies, especially in unmanned undersea vehicles, sensors, or artificial intelligence algorithms to process collected data. Compared to building new submarines, such capabilities could be developed and fielded quickly at a relatively affordable cost.

Introduction

India boasts the largest and most active Navy in the Indian Ocean region. It operates 29 major surface combatants and 16 submarines, multiple major naval bases on its coast and island territories, and 7 ongoing deployments sustaining a persistent presence across the ocean’s key maritime terrain.1 But its dominance will not last for long. China is building the world’s largest ocean-going navy, developing a series of ports in the Indian Ocean and has a declared intent to sustain a military presence there. The foundations of the military balance in the Indian Ocean are shifting, even if that has not manifested in Chinese military advantage yet. The trends are observable and unmistakable.

The foundations of the military balance in the Indian Ocean are shifting, even if that has not manifested in Chinese military advantage yet.

Australia and the United States have not articulated a coherent vision for managing these trends. In US policy, the Indian Ocean is subsumed within a wider Indo-Pacific strategy, where it is decidedly an economy-of-force effort, secondary to the more pressing military competition in the first island chain.2 In Australia, analysts consider the Indian Ocean the ‘second sea,’ a lower priority for political-military effort than archipelagic Southeast Asia and the Pacific.3 Much of this policy vacuity on the Indian Ocean reflects muddled thinking in both countries on India as a strategic partner. The Indian Ocean matters intrinsically for both Australia and the United States, but strategic planning for the region is impossible without a clear understanding of India’s evolving capacity and intent to manage regional security.

What can Washington and Canberra reasonably expect from India as a security actor in the Indian Ocean? With that in mind, how can the US and Australian militaries, in concert with India and other partners, position themselves to meet the region’s gravest strategic challenges?

This paper argues that India’s relative power in the Indian Ocean region is on the cusp of eroding rapidly. India has recently made important capability gains and maintains a significant level of operational activity, but new investments in naval capacity have declined, in large part because it has redoubled its military effort on its northern land border with China. India’s modest naval modernisation will not keep pace with China’s unabated naval expansion. As a result, India will struggle to exercise sea control in a future crisis or conflict.

In the face of this strategic reality, Australia and the United States should focus on military cooperation with India that prioritises relatively affordable and achievable capability improvements that would have a significant strategic impact. The highest-priority capabilities deserving collective effort are those required for anti-submarine and undersea warfare, because they are most likely to buttress their navies’ ability to exercise sea control. This paper first outlines the emerging strategic reality of China’s naval expansion, and then contrasts that with the reality of declining Indian investments. It concludes with recommendations for Australian and US policy makers to address these looming risks.

The looming challenge of China’s naval expansion

A snapshot of the Indian Ocean military balance may suggest Indian dominance, but the underlying trends point to a looming challenge. Since 2008, China has maintained a small flotilla of conventional vessels in the Gulf of Aden, subsequently supported by a military base in Djibouti, ostensibly for anti-piracy operations.4 That deployment has given the Chinese Navy valuable experience in expeditionary operations and a reason to continually patrol in and build familiarity with the Indian Ocean. China has also occasionally deployed various vessels, from submarines to telemetry-monitoring ships, for specific training, military-diplomatic, or intelligence-gathering purposes.5

China is not only rapidly growing its navy, but is also undertaking specific activities suggestive of a planned persistent military presence in the Indian Ocean. It is commissioning more large ships, which have greater range and endurance — that is, ships designed to traverse oceans.6 This includes 3 aircraft-carriers, 8 new guided-missile cruisers and dozens of guided-missile destroyers and frigates, with more of each type planned.7 In addition to its sole current military base at Djibouti, China is building dual-use ports across the Indian Ocean littoral, which would provide logistics support to an expeditionary naval presence around the ocean.8 The Chinese Navy can already use ports at Gwadar in Pakistan, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Chittagong in Bangladesh and Ream in Cambodia, and is developing others in Bangladesh and Myanmar.9 Authoritative Chinese military texts consider the Pacific and Indian Oceans to be a unified “two oceans region” where China should seek to build political influence and a lasting military presence.10

Although China’s specific long-term goals are unclear and variable, its expanding naval presence in the Indian Ocean gives it greater coercive leverage.

The scale of China’s naval ambitions for the Indian Ocean remains unclear. China depends critically on the energy and trade flows in the ocean and covets its fish and mineral resources. Beijing’s primary goal therefore, is to ensure freedom of navigation for its shipping. But it probably lacks the capacity to guarantee that for itself at least for the next decade, according to an influential Chinese maritime analyst; so, the best it can realistically aim for is to deter and occasionally challenge an adversary.11 Although China’s specific long-term goals are unclear and variable, its expanding naval presence in the Indian Ocean gives it greater coercive leverage. It could use its growing capacity in peacetime either to coerce India or smaller Indian Ocean states, or even in case of a conflict in the western Pacific, to safeguard its rear area. In peacetime or war, China’s naval presence generates greater strategic risk for India and its partners.

More specifically, there are multiple indications that China seeks to build subsurface capabilities — submarines and unmanned undersea vehicles (UUVs) — in the Indian Ocean. China’s submarine fleet is growing in numbers and performance, with a larger number of boats that are quieter and have longer endurance.12 China would face significant logistical challenges sustaining a presence in the Indian Ocean, especially since it currently operates only a modest fleet of 6 nuclear-powered submarines. But in coming years it could address those challenges with more nuclear-powered submarines, long-endurance UUVs and a base for its conventional submarines in Ream.13 China has also transferred submarines to the navies of Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar, and has built port infrastructure to support them in each country — which will not only build those countries’ dependence on Chinese security assistance, but could provide suitable facilities for China’s own submarines when they deploy to the Indian Ocean.14

Though China’s highest-priority adversary is the US Navy in the first island chain, there are also clear indications that China plans a longer-term undersea presence in the Indian Ocean. It has deployed an increasing tempo of dual-use survey ships to map the Indian Ocean, including into India’s exclusive economic zone.15 Its bathymetric survey ships are designed to gain an appreciation of the undersea operating environment and have operated often in the eastern Indian Ocean (see Figure 1).16 A persistent naval presence in the eastern Indian Ocean would provide China security against potential disruptions on the western approaches to the Straits of Malacca, Sunda and Lombok, through which the bulk of its own seaborne energy and trade must pass. It would also pose a particular coercive threat to the security of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, which rely on resupply from the Indian mainland.

Figure 1. Map indicating the locations and intensity of Chinese survey ship activity, 2020-24

A persistent Chinese submarine presence in the northern Indian Ocean — even a modestly sized force — would pose an unprecedented challenge for Indian planners. India would, for the first time, face an adversary that could effectively — if temporarily — interdict its shipping, including for resupply of its Andaman and Nicobar Islands territories. Meanwhile, the Indian Navy has traditionally been ‘weighted west,’ with most of its most powerful ships home-ported on the western seaboard — and for now comparatively less well postured to concentrate combat power in the east.17

This Chinese naval expansion matters because it will impinge on the ability of India and its partners to exercise sea control in a crisis or conflict. Sea control is the ability to freely operate naval forces — and deny the adversary’s ability to operate — at a particular time and place.18 In peacetime, navies generally enjoy freedom of navigation in international waters, but in contested waters in wartime they may need to use military force to establish sea control to achieve a variety of missions, such as projecting power ashore or securing sea lines of communication. Alternatively, a navy may pursue sea denial, whereby it seeks to disrupt its adversary’s ability to use the sea, especially if it lacks the ability to achieve sea control itself.

India and its partners, Australia and the United States, all seek unhindered use of the Indian Ocean, which includes the wartime ability to achieve sea control. The Indian Navy’s published doctrine explicitly lists sea control as one of its core missions, alongside sea denial and others.19 The latest US naval services doctrine considers sea control to be a critical enabling mission for its force globally.20 Australia’s recently-released National Defence Strategy, which considers the northeast Indian Ocean part of its “primary area of military interest,” calls for both sea denial and “localized sea control.”21 For all 3 countries, freedom of navigation in peacetime or sea control in wartime ensure open sea lanes that carry the energy and commodities on which they rely. This is especially critical for India, which unlike Australia and the United States has no alternatives — it is entirely dependent on the Indian Ocean for seaborne trade and energy. The United States would also require sea control in a major military conflict in the western Pacific, such as in Taiwan, because it would likely deploy reinforcements from Europe and the Middle East across the Indian Ocean to the conflict. China in contrast, may have reasons to challenge that sea control — that is, to seek sea denial — either to advance its influence in the Indian Ocean itself or to support its priorities in the Pacific.

In the Indian Ocean, submarines are the most likely means for China to challenge Indian or likeminded partners’ ability to achieve sea control. In general, a challenger may disrupt sea control with either subsurface, surface, or air forces.22 Subsurface forces are China’s best option in the Indian Ocean. Dispersed and stealthy, a relatively modest contingent of submarines and UUVs could disrupt or hold at risk Indian or partner navies’ operations across a wide area. With that capability in place, China would be able to execute sea denial missions without having to deploy large surface battle fleets to join and win a decisive battle, or deploy shore- or carrier-based air forces — both of which China is far less likely to be able to deploy persistently in the Indian Ocean. Regardless of its long-term goals, China’s looming subsurface presence will give it a dependable and persistent capacity to exercise sea denial. On its own, India will be unable to meet this challenge.

India’s slowing naval modernisation

The Indian Navy maintains an ambitious and increasing tempo of activities in the Indian Ocean. It participates in frequent and complex training exercises with international partners, conducts peacetime evacuation and humanitarian operations, and maintains round-the-clock deployments to project presence and assure security across the Indian Ocean region. It routinely offers security assistance to smaller regional states: for example by helping Mozambique, the Seychelles and Tanzania to monitor their Exclusive Economic Zones; providing coastal surveillance radars to Mauritius, the Maldives, the Seychelles and Sri Lanka; or gifting patrol boats to the Maldives, Seychelles and Sri Lanka.23 Since December 2023, the Indian Navy deployed more than 10 ships under Operation Sankalp for anti-piracy operations and to safeguard sea lines of communication in the Gulf of Aden and Arabian Sea, near but independent of the US-led coalition combating Houthi rebels.24 India has also embraced maritime security cooperation policies through multilateral forums such as the Indian Ocean Rim Association and minilaterals such as the Quad. These activities all signify a real and consequential Indian role in regional security.

However, India has slowed its investments for building future naval capabilities. Between 2000-2020, the Indian Navy benefited from some relatively significant capability investments. It decided to acquire for example, 6 Kalvari-class diesel attack submarines,25 4 Arihant-class ballistic missile submarines,26 the landing platform dock INS Jalashwa,27 3 Kolkata-class and 4 Visakhapatnam-class guided-missile destroyers,28 and 7 Talwar-class29 and 7 Nilgiri-class stealth frigates.30 India also acquired 12 P-8I long-range maritime patrol aircraft to significantly improve its anti-submarine warfare capability, and then decided to acquire 6 more.31 And in 2020, its Air Force began fielding fighters with air-launched BrahMos missiles at its southern bases for a maritime strike mission.32 Since 2020, naval force development has slowed.

Regardless of its long-term goals, China’s looming subsurface presence will give it a dependable and persistent capacity to exercise sea denial. On its own, India will be unable to meet this challenge.

The key pivot came with the outbreak of the 2020 China-India border crisis. Following multiple near-simultaneous incursions by Chinese troops across the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Ladakh, a skirmish left 20 Indian soldiers dead — the first loss of life on the LAC in 45 years — and with both sides scrambling for positional advantage, tensions peaked. For India, the crisis not only cratered trust in Chinese strategic intentions, but it very directly underscored the immediate threat to Indian territory and personnel on the northern land border. China’s expanding geoeconomic and strategic influence across the region and its growing power in the maritime, cyber, and space domains, all appeared distant and uncertain. In contrast, on the continental border, China’s direct military threat was clear and immediate — it had cost Indian lives and Indian territory.

Both India and China have deployed significant military reinforcements and built significant new military infrastructure near the border since 2020. In China’s case however, this was largely confined to the existing roles and resources of its Western Theatre Command — the joint theatre command on its border with India — which means it did not displace China’s higher planning priorities in the first island chain. In India’s case, with scarcer resources and ingrained beliefs about the vulnerability of its land borders, the Ladakh crisis has, initially at least, derailed the military’s incipient naval modernisation. Only 4 years have passed since the Ladakh crisis began, so the empirical evidence is modest, but it is sufficient to draw provisional insights. Defence budgets and procurement patterns suggest a probable turning point in 2020, with resources reallocated from naval modernisation to reinforcement of the northern border.

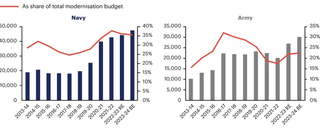

Budget allocations among different military services offer one telling indication. For several years, the Navy had been attracting a growing share of the defence modernisation budget, while the Army’s share had been declining. This trend peaked however, in the FY2021-22 budget.33 Since the Ladakh crisis the Defence Ministry changed course: the Army’s share of modernisation has grown while the Navy’s has shrunk, though the capital budget of the naturally capital-intensive Navy remains larger in absolute terms (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Indian Navy and Army expenditure (tens of millions of rupees) and share of defence modernisation funding, FY2013-14 to FY2023-24

Granted, some very noteworthy naval capabilities have entered service since 2020, giving the impression that naval modernisation has continued or perhaps even been spurred by an inflamed antipathy for China. In reality however, all of these major developments were initiated before 2020, reflecting pre-crisis strategic priorities. With great fanfare, the Indian Navy commissioned its first indigenously-built aircraft carrier, the INS Vikrant in 2022 — although that procurement was approved by government as far back as 1999. In August 2024, it commissioned its second nuclear ballistic missile submarine, the INS Arighaat. The third ballistic missile submarine, which was launched in 2021, will probably be commissioned in 2025.34 These vessels are no different to the several other surface ships and submarines that have been launched or commissioned since 2020, as a result of acquisition decisions made in previous decades.

The Indian Navy also commissioned its first squadron of MH-60R anti-submarine warfare helicopters in 2024 — although that procurement was approved by the government in 2018.35 The Navy is also on the cusp of acquiring 15 MQ-9B high-altitude, long-endurance drones, although that procurement was initiated in 2016, and has actually been down-sized from the original Navy request for 22 drones.36 In fact, since Ladakh, some of the investment originally intended for the Navy has been reallocated to the Army and Air Force, which did not initially bid for any drones, but will now receive 8 drones each for managing continental threats.

The most significant naval acquisition decision that has occurred since 2020 were extensions of existing capabilities. The Defence Ministry decided in July 2023 to procure 26 Rafale-M fighters to serve as the new carrier Vikrant’s air wing, and 3 additional Kalvari-class submarines.37 The carrier-borne fighters, of course, are a necessary and implied component of the long-running carrier acquisition, rather than a new decision to acquire a new capability. The submarines similarly were the fulfillment of an earlier procurement that India had been considering, but declined in 2016.38 Other naval systems, from torpedoes to towed-array sonars, have also been approved since 2020, to improve the capabilities of existing platforms.39 But they pale in comparison to the new naval platform acquisitions approved prior to 2020, and do not signify a shift in strategic priorities.

Moreover, the Navy’s most prized and high-profile modernisation requests — advanced submarines and aircraft carriers — continue to be stalled. The government granted an ‘acceptance of necessity,’ or in-principle approval to procure diesel attack submarines with Air-Independent Propulsion, known as ‘Project 75(I),’ in 2007. The project has languished through multiple inconclusive tendering cycles — requiring multiple renewals of government approvals — ever since.40 For the surface fleet, the Navy has been seeking the government’s ‘acceptance of necessity’ approval for its second indigenous aircraft carrier since 2015, without success:41 most recently the Defence Acquisition Council declined to grant the approval when it last considered the proposal in November 2023.42 The government also declined to approve the highly anticipated acquisition of new stealth frigates known as ‘Project 17B,’ when it considered the proposal in July 2024.43

In contrast, the Army and Air Force have continued and incrementally expanded their capability investments since 2020. Jolted by the Ladakh crisis for example, the Indian Army in 2021 requested 350 light tanks for operations on the LAC; the government moved with relative alacrity to approve the acquisition in 2022; and the indigenously-developed prototype was ready for testing by 2024.44 The government also approved an Air Force bid in 2021 to procure its first tranche of Tejas Mk1A fighters, approving a second tranche in 2023 for a total of 180 aircraft, even though none have been delivered to date.45 It also approved the Air Force acquisition of mid-air refueling aircraft46 and Army and Air Force acquisitions of combat helicopters.47

The Indian Government’s emphasis on indigenous production under the government’s Atmanirbhar Bharat scheme, carries a worthwhile strategic logic of self-reliance, but comes at the expense of timeliness and quality.

In sum, the picture that emerges suggests that investments in the Indian Navy’s future capabilities have been deprioritised since 2020. They are not keeping pace with earlier rates of Indian Navy capability development, let alone accelerating to keep pace with the impending growth of China’s naval presence in the Indian Ocean.

India will find it near impossible to correct this impending shift in naval power. The political reality is that a life-and-death confrontation on the country’s soil at the LAC demands greater urgency and attention than a potential challenge at some indeterminate part of a vast ocean, at some indeterminate time in the future. Even with a politically unpalatable strategic re-evaluation, naval capability development entails especially long lead times, from government approval to fielding, and these are exacerbated by India’s characteristic procurement delays. The Indian Government’s emphasis on indigenous production under the government’s Atmanirbhar Bharat scheme, carries a worthwhile strategic logic of self-reliance, but comes at the expense of timeliness and quality.48 Efforts to recapitalize the major surface combatant or submarine fleet will realistically take decades. This problem is, of course, not confined to India. The US shipbuilding industry has shrunk drastically in recent decades, which imposes significant delays on naval force planning, and is compounded by inadequate crewing and maintenance capacity.49 In contrast, China has already laid the foundations for a persistent naval presence in the Indian Ocean that is likely to materialise much more quickly. The conventional military balance in the Indian Ocean is on the cusp of shifting.

An agenda for naval cooperation

As the preceding analysis shows, China is poised to rapidly expand its naval presence in the Indian Ocean, especially with subsurface forces and especially in the eastern Indian Ocean. This will pose a risk — in both peacetime and conflict — to Australian, US, and Indian security interests. These countries, individually and collectively, lack the industrial capacity to arrest this shifting military balance. India, the resident great power in the Indian Ocean, recognizes the risks of China’s expansion, but since the 2020 Ladakh crisis has slowed its naval capability development. Australia and the United States also both consider the Indian Ocean to be a secondary priority.

The only viable option to offset China is international cooperation. More specifically, given the nature of the challenge in the Indian Ocean, the most urgent priority for naval cooperation between Australia, the United States and India should be anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and undersea warfare (USW). These partners already have technological advantages and greater tactical experience in ASW than China. Taken together they can amass potent ASW and USW force. But to realise their combined advantage, they must improve their ability to operate seamlessly together.

Given the nature of the challenge in the Indian Ocean, the most urgent priority for naval cooperation between Australia, the United States and India should be anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and undersea warfare (USW).

In the Indian Ocean, ASW cooperation is already increasing between India, Australia and the United States. They already enjoy a degree of equipment interoperability — for example, they all operate variants of P-8 multi-role aircraft and MH-60R helicopters, which are both state-of-the-art ASW platforms. The quadrilateral MALABAR series of exercises, which also includes Japan, consistently include ASW activities.50 But this cooperation remains episodic, based on training events, and is not persistent and routine let alone automatic. Worse, this type of activity does not build long-term ASW capacity for the partner countries. More enduring ASW capability development, in the absence of major new platform acquisitions, could take at least 3 broad forms: data sharing, operational cooperation and technology co-development.

Data sharing

First, partners such as India, Australia and the United States could share more data and more routinely, regarding the undersea domain. Each Navy collects ASW-relevant data from a range of sensors deployed on ships, submarines, aircraft and fixed sites. Given that subsurface forces and operations depend critically on secrecy, this data is generally extremely sensitive. Thus the recent announcement that Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom will automatically share data from P-8 aircraft-deployed sonobuoys, under the auspices of AUKUS Pillar 2, represents a novel and significant level of operational integration.51 In the Indian Ocean, India and its partners such as Australia have begun to share intelligence reporting on the region, however that sharing remains manual and episodic: it is not comprehensive and certainly not automated.52

Sharing ASW-relevant data is not a binary, all-or-nothing choice. Sharing can be calibrated in multiple dimensions — data from different sensors can be treated with different levels of sensitivity and shared with different partners.53 The United States and Australia, as close Five Eyes allies, will always share more sensitive data with each other than with India. Over time, all of these partners could share more data as they develop greater trust in each other’s strategic intentions and in their data handling systems and practices. Data could also be calibrated and tiered among different partners, to include other capable and likeminded navies. The United Kingdom for example, is another Five Eyes ally with a long history of close subsurface cooperation with the United States and recently redoubled its submarine and technology partnership with the United States and Australia through AUKUS. France boasts a highly capable Navy with island territories and strategic partners in the Indian Ocean. Japan has another highly capable Navy: it’s one of the most important US allies in Asia; a member of the Quad; and provisionally, also AUKUS Pillar 2. Calibrating data-sharing among these partners will be a dynamic and complex arrangement, but it would be technically feasible. It only requires political will from partner navies and their national leaders. Over time, incrementally greater access to different sources and sensors would create a powerful incentive for each partner to commit to sound information assurance practices and sharing more data.

Operational coordination

Second, as India and its partners build trust, they could incrementally commit to greater coordination of ASW operations. An aspirational goal for this could be the establishment of a combined clearing house where they share situational awareness and coordinate some ASW operations. Such a center, nominally called a ‘Combined Anti-Submarine Warfare Operations Center’ (CASWOC), would be a separate, stand alone combined headquarters in the Indian Ocean littoral — perhaps for example, at HMAS Stirling. It would include a fusion center for data feeds and a multinational operations staff, ideally with rotating command.

This coordination again, could be calibrated over time. Each participating member Navy would of course retain sovereign control of its ASW assets and only share information and coordinate operations in accordance with its risk acceptance at any given time. But having a CASWOC established would provide a ready-made venue to enable integrated operations at short notice — which would be invaluable in case of a regional crisis. Over time, it would enable greater trust and an expectation of combined effort. In this way, the CASWOC could draw inspiration and lessons from the Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar, where the United States leads a 19-country coalition coordinating air operations. The CAOC, established in the midst of wartime operations in 2002, has tested and improved procedures, deepened interoperability and cultivated trust across a generation of officers from different partner countries.54

The CASWOC would not be intended to replace any existing capability or limit any member’s operational freedom — quite the contrary, it would build a capability for each member that does not currently exist. Tactically for example, a CASWOC would enable a participating member Navy to hand off its tracking of a Chinese submarine to the ASW assets of another trusted partner, to ensure that Chinese subsurface operations do not exploit gaps and seams between likeminded states’ surveillance. Each participating partner would gain a wider appreciation of the operational environment and have a stake in promoting each other’s ASW capabilities and capacity.

Technology co-development

Third, in parallel to these operational activities, likeminded partners could focus on co-developing and co-producing new ASW and USW technologies and capabilities. As argued above, recapitalisation of India’s attack submarine fleet is a torturous process. But more modest systems, such as UUVs, sensors, or artificial intelligence algorithms to process collected data, could be developed and fielded relatively quickly and at relatively low cost.55 For example, the US-based firm Anduril, along with an array of Australian firms, has co-developed an Extra-Large Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (XL-AUV) for the Royal Australian Navy.56 There are many use cases for UUVs, of various sizes and capabilities, which have yet to be fielded.57 Alternatively, India and its partners could co-develop ASW sensors, which could be deployed on UUVs, airborne drones, satellites, or at fixed sites on the seabed. Co-developed sensors would also presumably allow the collected data to be more easily shared among participating partner navies.58

India and its partners have both the supply and demand for new, co-developed UUVs and sensors, designed for ASW missions. India, Australia and the United States all have thriving defense innovation ecosystems and burgeoning networks between them: for example, AUKUS Pillar 2 which unites the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom and soon Japan, or the Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET) between the United States and India. Those innovation networks, often comprising start-up firms developing dual-use technologies, have significant capabilities in automation, AI, quantum sensing and subsurface vehicles; and the Indian, Australian and US navies have a clear and urgent operational need for such capabilities.

Conclusion

This agenda for naval cooperation with India is not without risk. Most particularly, ASW and USW are especially sensitive, even among the closest of allies because their effectiveness depends critically on secrecy. Thus, an agenda that suggests more sharing of sensitive data, more coordination of sensitive operations and more co-development of sensitive technologies, will encounter significant bureaucratic resistance and generate genuine risk. Transfer of technology has for decades been a key goal and a key obstacle in India-US defence cooperation. An agenda built around sharing data and operational coordination will confront many of the same hurdles.

Washington will be concerned for example, that sensitive data shared with India may inadvertently wind up in the hands of adversarial third parties, especially Russia. But just as technology transfer concerns can be allayed through technical and procedural assurances — resulting ultimately in the promised transfer of jet engine technology — data sharing risks can be similarly mitigated through technical and procedural means and managed as the partners build trust over time.

This agenda for naval cooperation will require political willingness in each capital to deepen cooperation with its partners in the service of a collective mission

Conversely, New Delhi will be concerned for example, that the United States will prove to be an unreliable partner, prone perhaps to condition access to data and operational coordination on other political demands. But just as technology transfers require the United States to accept some calculated risk, building trust with India may require the United States and Australia to accept risk in offering more data than they initially receive, as a sign of good faith and trustworthiness. This may seem unpalatable, but the alternative may be that India builds niche capabilities independently, or even with a partner such as Russia. In such cases, Australia and the United States would forego not only the operational benefits of partnering with India, but also the strategic opportunity to build trust and consolidate a shared vision with India.

More broadly therefore, this agenda for naval cooperation will require political willingness in each capital to deepen cooperation with its partners in the service of a collective mission. India since 2020 has observably slowed its investment in capabilities for projecting power in the Indian Ocean. This is not because New Delhi misapprehends the threat or refuses to deal with it; it is because the government faces a lethal threat and an acute sense of military vulnerability on its border. The capability development scenario is not much rosier in Australia or the United States. The defence industrial base of each of these 3 partners is already stretched, making recapitalisation of their submarine forces a lengthy and uncertain prospect. India is years behind its planned procurement of submarines and the United States and Australia will struggle to build the requisite numbers of submarines they have already committed to building under AUKUS. These partners cannot build enough naval capacity to compete directly with China. Their only option is to offset their mass disadvantage with technology and international cooperation.