Introduction

Since the 2021 announcement of trilateral cooperation on nuclear-powered submarines through the AUKUS partnership, key stakeholders in Canberra, London and Washington have all offered regular assurances of staunch bipartisan support for the initiative. In the United States, many have interpreted the passage of the Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) in December 2023 as a powerful demonstration of such support from both chambers of the US Congress. The bill provided long-awaited authorisation for the transfer of Virginia-class submarines to Australia, a legal pathway for Australian financial contributions to the US submarine industrial base, and a conditional carve-out for Australian companies from onerous US defence export controls.

However, bipartisan support has proved insufficient to inoculate AUKUS from protracted and unpredictable Congressional spending negotiations. The FY2024 NDAA may have been signed into law by President Joe Biden on 22 December 2023, but the appropriations bills that would resource its implementation remain the subject of intense Congressional debate. The complications do not end there. Even as Congress races to appropriate a complete defence budget for this year before interim funding expires on 8 March, reports are already surfacing that “the knives are out” for some of the Pentagon’s key capabilities in the forthcoming FY25 presidential budget request. Virginia-class submarine procurement plans are among those programs on the chopping block.

To be clear, this is not a direct shot across the bow of AUKUS. Congressional disputes over spending are not new, and funding delays in a single fiscal year are far from a nail in the coffin for US commitment to the multi-decade AUKUS agreement. But it could be a case of errant friendly fire. The current impasse is a reminder that the timely implementation of AUKUS is at the mercy of the bigger US appropriations picture. This is especially true in a Congress where the effects of political polarisation are being exaggerated by the forthcoming US presidential election. If success for AUKUS is measured by the three countries’ ability to move at the speed of strategic relevance, then protracted funding disputes in Congress figure as a key factor in determining the speed and scope of success.

The role of US Congress in the AUKUS partnership

In recent months, many Australian and UK experts have become fixated on the potential implications of the 2024 US presidential election for the future of AUKUS Pillar I. Yet the current appropriations fight underscores the central and enduring role that political dynamics in Congress, in addition to the executive powers of the president, play in enabling or delaying Australia's acquisition of nuclear-powered, conventionally armed submarines.

Since the announcement of the AUKUS optimal pathway by the three heads of state in March 2023, Congress has been central to initial implementation efforts, passing key authorisations for the Pentagon to receive Australian investment and workers, to transfer submarines to Australia and to reform US defence trade export controls to enable trilateral defence industrial and technology cooperation. Indeed, the Hill will arguably remain the locus of AUKUS Pillar I resourcing going forward, given that Congressional approval is critical for the timely appropriation of funding each year for submarine development and procurement. As the White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan has made plain in relation to current funding disputes: “there is no magic solution” to America’s national defence and security priorities absent Congressional appropriations; “there’s not another path for us to go down to get the kind of resources that we are asking Congress for here.”

This makes understanding the nature of Congressional political dynamics and how they affect the appropriations process all the more important for Australia. Over the past decade, flirting with wider government shutdowns and operating under continuing resolutions have become a standard order of proceedings in Congress. Yet the current political dynamic of the 118th Congress is proving to be uniquely fraught for spending legislation, with major implications for the timely implementation of the AUKUS optimal pathway. Such is the state of political polarisation in Congress, particularly in the House of Representatives, that a small group of fringe-right lawmakers aligned with former president Donald Trump have proven able to pressure the incumbent Speaker of the House of Representatives to delay or obstruct the passage of key appropriations legislation unless their demands on issues including abortion policy, border security issues, and Ukraine funding are met. This group have proven equally unwilling to work with their Republican colleagues or Democrat counterparts, with some prominent figures stating that a government shutdown is “not the worst thing” and that Republicans “shouldn’t be joining hands with Democrats just to show we can govern or we can get things done.”

On the positive side, Congress has to date been able to avoid a government shutdown for FY24, and Speaker of the House of Representatives Mike Johnson has made it “unequivocally” clear that he will do his best to avoid a complete shutdown come 1 March, when interim budget authorities are set to expire. On the other hand, the US government has now been operating under a Continuing Resolution (CR) – a stop-gap interim budget keeping the government running at existing funding levels in lieu of a new budget agreement – for over 150 days since the first CR for FY24 was signed on 30 September 2023. That streak looks set to continue, with three out of four temporary spending measures approaching expiry after 1 March remaining the subject of contention in current negotiations. As such, prominent lawmakers expect that while a shutdown will likely be averted, Congress will require yet another CR (out to March 22 2024) to buy time for inter-party negotiations to bear fruit.

On top of the immediate requirements of avoiding a shutdown and passing the FY24 budget, new budget limits already appear to be having negative impacts on forward defence spending plans. To satisfy the conditions of the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA), a deal reached by President Biden and congressional leaders in 2023 that caps government discretionary spending, it seems that Department of Defense capabilities across the services will face cuts in the administration’s FY25 budget request, including for Virginia-class submarines. If preliminary reporting on Biden’s forthcoming FY25 budget request is anything to go by, then the US Navy is poised to reduce its annual request for Attack-class submarines from the industrial base from two to just one in the next financial year.

On the face of it, the Biden administration’s expected underfunding of submarine acquisition in its FY25 request looks to be a step backwards in the realisation of the AUKUS pathway on schedule. It runs contrary to assessments from Navy officials and Congresspeople that US submarine production would have to, instead, increase to 2.5 per year for the transfer of Virginia-class submarines to Australia under AUKUS to be viable. House Armed Services Committee Chairman Mike Rogers and Ranking Member Adam Smith wrote in a letter to President Biden just last month that: “any deviation from the planned cadence of the construction and procurement of two submarines per year will reverberate both at home and abroad, with allies and competitors alike.”

The timely implementation of AUKUS is certainly vulnerable to becoming collateral damage each year as the president and Congress pass the parcel on budget appropriations.

Indeed, US lawmakers have been explicit in their recognitions that, for the United States to hand over the keys to three Virginia-class submarines to Australia, prevailing shortages in the US fleet must be remedied. A July 2023 letter to the Biden administration from 25 Republican lawmakers was frank that, the transfer of submarines, “if implemented without change” to the US rate of production, “would unacceptably weaken the U.S. fleet even as China seeks to expand its military power and influence.” Investment in the national submarine industrial base and the progression of AUKUS are in this regard mutually constituting.

Beyond regular defence appropriations, AUKUS equities are also implicated in the long-delayed National Security Supplemental bill requested by President Biden in October 2023. Amongst the contents of the US$95 billion bill, which consists largely of Ukraine and Israel aid and border security funding, is an allocation of US$3.3 billion (3.4 per cent of the total bill) to the US submarine industrial base, mostly for increasing submarine production rates. Though this bill comfortably passed the Senate in February, it remains stalled in the House. House Speaker Johnson has opposed this legislation because it “failed to meet the moment” on border security issues (despite containing significant concessions from the White House and Congressional Democrats on this issue), while alleging that new Democrat demands have shifted the goalposts for negotiations. As such, Johnson has so far refused to facilitate a House floor vote on the supplemental that would by most counts see the bill pass with majority support. Though the reasons for this opposition are numerous (and fluid), it is widely reported that House Republicans are unwilling to concede an election issue for presumptive Republican nominee Donald Trump by approving the Biden administration’s border policy.

A game of fiscal chicken

Considering the current appropriations fight in Congress, those in Australia already anxious or downright cynical about the viability of AUKUS Pillar I – the conventionally-armed, nuclear-powered submarine acquisition element of the agreement – would no doubt ask whether the US President and Congress were playing “fiscal chicken” with AUKUS. Though the risks can be easily overstated, the timely implementation of AUKUS is certainly vulnerable to becoming collateral damage each year as the president and Congress pass the parcel on budget appropriations.

This is particularly possible given that new discretionary spending caps, coupled with growing nondiscretionary expenses for defence personnel, have reduced the space available to Congress and the White House to negotiate increases in FY25 defence spending above the President’s budget request. In 2021 and 2022, the White House requested funding for the Department of Defence well below what many lawmakers – and many analysts – believed to be the necessary levels required to implement the US National Defense Strategy. This effectively punted the task of rightsizing national defence spending against those requirements to Congress, where the issue invariably became a flashpoint for debate between defence hawks (those in favour of greater defence spending) in Congress to duke it out with fiscal conservatives (those in favour of limiting government spending).

Regardless of whether this was a deliberate fiscal buck-passing tactic, this approach seemed to work out for the administration, with Congress adding tens of billions of dollars to two of the administration’s previous three defence budget requests (See Table 1). For example, in FY22, Congress found an additional US$25 billion to buttress the Department’s US$715 billion request. It nearly doubled that increase in FY23, adding around US$45 billion to the Pentagon’s US$773 budget request, specifically to offset for rampant inflation and to accelerate the implementation of the 2022 National Defense Strategy.

Figure 1: Difference between presidential budget requests for the Department of Defence (Pentagon only) and NDAA authorisations by Congress, FY2022-2025 (USD)

| Year | Presidential Request | NDAA | Difference ($) | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY22 | $715 billion | $740.3 billion | + $25.3 billion |

+ 3.5 per cent. |

| FY23 | $773 billion | $816.7 billion | + $43.7 billion |

+ 5.6 per cent. |

| FY24 | $842 billion | $841.4 billion | – $0.6 billion |

– 0.07 per cent. |

| FY25 | $850 billion | –––– | –––– | –––– |

By comparison, the Biden administration’s request for FY25 is expected to come at the level set by the FRA spending caps, leaving almost no room for Congress to add extra funding unless they breach that legislation or revive old measures utilised under the 2011 Budget Control Act to circumvent restrictions on defence spending. Given that the act only limits Congressional appropriations – not the president’s budget request – it is striking that the administration appears to have conceded space at the starting line of negotiations, something which has led seasoned defence budget analysts to observe that the budget environment is dictating national strategy, and not the other way around.

Implications for the Pentagon – and for Australia

The degree of uncertainty about timing and funding is an unwelcome impediment to the preparation of the US defence industrial base and bureaucracy for AUKUS implementation. As the Australian Government transforms its own system to meet the expectations of its US counterpart, it will be looking for commensurate demonstrations of commitment. More importantly, however, the status of such appropriations determines the Pentagon’s capacity.

Regardless of whether protracted budget debates are driven by political point-scoring or bureaucratic inertia, the outcome – stop-gap funding that stalls key priorities – is damaging for the Pentagon and for the progression of AUKUS. Reportedly, for each day that the regular appropriations bills are not passed and the Pentagon operates under a CR, US$300 million in buying power is lost. The other potential outcome, a partial government shutdown as soon as the end of this week and a complete government shutdown the week after if Congress is unable to reach a deal on key points of conjecture, is even more concerning.

In the event that Congress cannot pass a complete defence appropriations bill before 8 March, experts, lawmakers and military officers alike have voiced their fears that the Pentagon may be asked to operate under a year-long CR. For the Pentagon, this has had the effect of delaying major military modernisation efforts, slowing the acquisition of essential capabilities, and preventing both new programs from commencing and the reprogramming on funding to support priority initiatives. Officials from the Department of Defense have been frank that current “brinksmanship creates uncertainty, increased costs and delays” and that they “can’t out-compete the PRC with one hand tied behind their back for three, four, five or even six months of every fiscal year.”

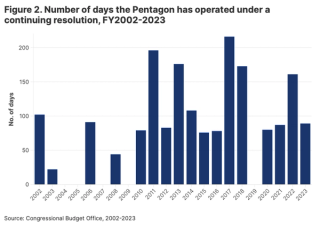

Yet, those material effects on US military readiness and modernisation have not provided sufficient incentive to grease the wheels of annual appropriations. By its own count, the Department of Defense has spent the equivalent of “nearly five years” since 2011 operating under CRs, and has only once entered a new fiscal year with a readymade appropriated budget (see Table 2). Should it eventuate, a year-long CR for FY24 – which would be a first for the Pentagon – would mean that the Department of Defence will have spent more than a third of the last fifteen years operating under fiscal constraints.

The Pentagon has abundant experience operating under CRs and it will by no means bring AUKUS progress to a standstill as it navigates new constraints. But it does make the task of implementation more complicated. In the face of sharpening FY2025 budget lines, the Pentagon will likely have to rely on reprogramming other elements of the budget, bandwidth for which is already limited by pressures from below (pay raises for troops and other personnel costs) and above (spending caps), or funding discreet programs or initiatives through supplemental spending bills.

USSC experts have pointed out previously that navigating US defence appropriations delays are now a familiar phenomenon for US allies in Asia. But considering the cumulative drag effect that CRs have on the implementation of the defence elements of US Indo-Pacific strategy, this is far from a happy norm. A year-long CR would delay funding increases for several key lines of effort, including for reform to the US submarine industrial base. AUKUS itself will undoubtedly continue – the pre-eminence AUKUS has acquired for the US strategy for strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific assures it - but such delays and stalemates will make it harder to follow the optimal pathway the three countries agreed with requisite urgency.

The future of AUKUS in the US system

The current state of uncertainty underscores is the precarious nature of the US legislative process, which remains among the greatest variables shaping the delivery of AUKUS, especially Pillar I. In other words, the current funding debate is but a single episode in the uphill battle to the implementation of the AUKUS partnership.

It is possible that the proposed cut to the US Navy’s submarine order for FY25 is a tacit recognition of existing constraints within the US industrial base. Despite the US Navy’s stated aim of a “2+1” schedule, Navy officials estimate that the two major contractors, General Dynamics Electric Boat and Huntington Ingalls Industries, averaged only 1.2 Virginia-class boats annually from 2018-2023. This rate is not expected to lift to two boats annually until 2028. At that rate, the Navy would “miss” delivering 5.6 submarines from 2019 to 2029. So, even if a request was made at the usual level, it is uncertain whether US shipbuilders could rise to meet it.

The budget debate has had the second order effect of highlighting the differences in priority afforded to AUKUS in Australian and the United States. Where AUKUS has seemed to act as a new organising principle for Australian defence planning, for the United States, its Virginia-class program does not even stand at the forefront of its submarine capabilities. Previous continuing resolutions have included “anomaly” exceptions for Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine program funding. With tightened purse-strings making prioritisation all the more important and the Columbia-class securing preferential status as a leg of the US “nuclear triad”, the resourcing of AUKUS implementation faces further complications.

The imperatives of strategic competition compel continued US commitment to AUKUS, and agreement about the necessity of cooperation with Indo-Pacific partners is one of the few areas of agreement in an otherwise bitterly divided Congress. But that doesn’t mean that it will always be smooth sailing for Australian equities.

.jpg?rect=0,80,3000,1989&fp-x=0.5&fp-y=0.44772296905517583&w=320&h=212&fit=crop&crop=focalpoint&auto=format)