Executive summary

- Australia’s history demonstrates that there is no reason in-principle why Australia cannot enjoy the world’s highest standard of living, underpinned by world-beating productivity.

- This means narrowing, if not closing, the gap with US productivity. Economic theory predicts long-run convergence in living standards (unconditional convergence), with productivity growth playing an important role in driving that convergence.

- In terms of labour productivity, Australia is around 20 per cent below the level of the United States.

- Australia’s ‘2025 aspiration’ to be in the top ten countries in terms of living standards, as set out in the 2012 Australia in the Asian Century White Paper, has yet to be met, with a standard of living as of 2018 the 12th highest in the OECD.

- In 2018-19, Australia’s labour and multi-factor productivity went backwards, while growth in per capita income slowed to just 0.3 per cent.

- This report examines the long-run relationship between Australian and US productivity and living standards. Statistical tests of the relationship between US and Australian living standards are consistent with the long-run convergence predicted by economic theory and provides evidence for a long-run relationship between Australian and US productivity.

- The report argues that the relative openness of the Australian economy over time is an important determinant of productivity by allowing it to import productivity trends from the global frontier represented by the United States.

- Measures of the globalisation of the Australian economy predict Australian productivity and help explain the recent weaker trend in ways that competing explanations do not.

- Australia is only the 58th most economically globalised economy on one measure, just above the United States at 59th. But because the United States is on the frontier of global productivity, it is not as reliant as Australia on international connectedness for its productivity growth.

- The report estimates that a one per cent gain in US labour productivity raises Australian labour productivity by 0.95 per cent, indicating that Australia imports productivity gains from the global frontier.

- A one per cent improvement in Australia’s economic globalisation score raises Australian labour productivity by around 0.3 per cent.

- Australia could enjoy labour productivity gains of up to 9 per cent by matching the level of globalisation found in other economies.

- The report also provides a basis for estimating the labour productivity losses from any reversal in globalisation due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- If Australia were to return to the level of economic globalisation prevailing in 1976, labour productivity would be around 12 per cent lower, holding other influences constant.

- Re-booting the globalisation of the Australian economy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic must be a priority for Australian policymakers if productivity and living standards are to recover.

Introduction

In the late-19th century, Australia enjoyed a standard of living higher than any other country in the world, including the United States. Between 1870 and 1890, Australia’s income per capita was 40-50 per cent above the level of the United States.1 Labourers in Sydney enjoyed wages double the level prevailing in Chicago or San Francisco.2 Australia did not just occupy the frontier of global living standards, it defined it.

This period of ‘Australian exceptionalism’ is often attributed to its natural resource endowment, but it was the skill Australians brought to bear in exploiting this endowment that yielded such high living standards.3 Australia’s world-beating standard of living was the result of world-beating productivity.4 While half of Australia’s income lead over the United States was due to higher labour force participation, half was due to its higher labour productivity.5 Economic historians puzzle over the deeper determinants of this superior productivity performance, but this report will argue that It was a function of very high levels of economic openness and integration with a then rapidly globalising world economy. Australia’s exceptional productivity performance came despite the ‘tyranny of distance’ and a population before 1900 of less than four million.

This period of ‘Australian exceptionalism’ did not last. The United States caught-up with Australian living standards around 1900 and moved ahead during and after World War Two. Australia’s embrace of tariff protection, centralised wage fixing and more restrictive immigration from around the time of Federation in 1901 weighed on Australia’s economic performance. The Lyne Tariff, in particular, adversely affected international trade flows.6 This inward turn coincided with the collapse of the first era of globalisation after 1914. Between 1890 and 1939, Australia’s average standard of living grew only slowly, and the Australian economy underperformed.7

Australia’s ‘2025 aspiration’ to be in the top ten countries in terms of living standards, as set out in the 2012 Australia in the Asian Century White Paper, has yet to be met, with a standard of living as of 2018 the 12th highest in the OECD.

The post-World War Two period saw a return to greater prosperity, but ‘the policy and institutional environment in Australia in the post-war decades reinforced the closed, inward-looking and rigid nature of the economy.’8 In relative terms, Australia’s productivity and living standards remained stuck below the new global frontier occupied by the United States.

The reform era of the 1980s coinciding with a new wave of globalisation contributed to a productivity surge in the 1990s, but with the US economy also experiencing productivity gains, Australia had to close a gap with a moving target. More recently, Australia has shared in a global productivity slowdown since 2000, with a labour productivity performance close to the median of advanced economies. It has underperformed in terms of total or multifactor productivity, partly due to the long lead times for the mining investment boom to yield increased output.9 In terms of labour productivity, Australia is around 20 per cent below the level of the United States. Australia’s ‘2025 aspiration’ to be in the top ten countries in terms of living standards, as set out in the 2012 Australia in the Asian Century White Paper, has yet to be met, with a standard of living as of 2018 the 12th highest in the OECD.10

While much has been made of the contribution to national income from the terms of trade boom from 2003 to 2011, this improvement in the international purchasing power of Australian output would have meant little in the absence of openness to international trade and investment. Measures of globalisation have stagnated since the 2008 financial crisis, broadly coinciding with the productivity slowdown.11 The COVID-19 shock has delivered a new blow to globalisation that will further weigh on Australia’s productivity and living standard. Re-booting globalisation will be a key task facing Australian policymakers in the wake of the pandemic. As a trading economy, Australia’s economic fortunes have been consistently tied to trends in economic openness and globalisation.

Definitions

Productivity: is a measure of the rate at which output of goods and services are produced per unit of input, most notably labour and capital. It is calculated as the ratio of the quantity of output produced to some measure of the quantity of inputs used. Many factors can affect productivity growth. These include technological improvements, economies of scale and scope, workforce skills, management practices, changes in other inputs (such as capital), competitive pressures and the stage of the business cycle.

Labour productivity: is the ratio of output to hours worked. Over the long term, wages generally grow in line with labour productivity. Labour productivity is a key determinant of income growth.12

Multifactor or total factor productivity (MFP/TFP): is the ratio of output to combined input of labour and capital. It is generally considered to be a more comprehensive measure of technological change and efficiency improvements than labour productivity. Usually, the growth in labour productivity exceeds the growth in multifactor productivity. The difference between the two is the contribution from ‘capital deepening’ or the capital-labour ratio. That is, the accumulation of more and better capital equipment over time helps to make workers more productive.

Source: Adapted from Productivity Commission, PC Productivity Insights, 2020.

Australia’s history demonstrates that there is no reason in-principle why Australia cannot enjoy the world’s highest standard of living, underpinned by world-beating productivity. In today’s terms, this means narrowing, if not closing, the gap with US productivity. Economic theory predicts long-run convergence in living standards (unconditional convergence), with productivity growth playing an important role in driving that convergence. While some smaller European countries enjoy higher levels of aggregate productivity than the United States, this is due to differences in industry composition and labour utilisation rates rather than superior technology or know-how. The United States still largely defines the global technology and thus the global productivity frontier.

Raising productivity growth has long been a priority for Australian policymakers, but formulating and implementing productivity-enhancing reforms is a task that has largely eluded Australian politicians since the demise of the Howard government in 2007. In 2018-19, Australia’s labour and multi-factor productivity went backwards, while growth in per capita income slowed to just 0.3 per cent.13 The current government has instituted five-yearly productivity reviews that have identified reform options valued at about $80 billion in terms of increased output.14 The Productivity Commission characterises these policy options as ‘taking out the microeconomic garbage,’ but the proposed reforms are mostly inward-looking compared to the big picture reforms that internationalised the Australian economy in the 1980s and 1990s, restoring some of the openness the Australian economy enjoyed in the late 19th century. Former Productivity Commission Chair Gary Banks’s 2012 ‘to do’ list of reforms for the most part remain on the shelf, unimplemented.15

Raising productivity growth has long been a priority for Australian policymakers, but formulating and implementing productivity-enhancing reforms is a task that has largely eluded Australian politicians since the demise of the Howard government in 2007.

This report examines the long-run relationship between Australian and US productivity and living standards. Statistical tests of the relationship between US and Australian living standards are consistent with the long-run convergence predicted by economic theory, and provides mixed evidence for a long-run relationship between Australian and US productivity. The report argues that the relative openness of the Australian economy over time is an important determinant of productivity by allowing it to import productivity trends from the global frontier represented by the United States. Measures of the globalisation of the Australian economy predict Australian productivity and help explain the recent weaker trend in ways that competing explanations do not.

The report estimates that a one per cent gain in US labour productivity raises Australian labour productivity by 0.95 per cent, indicating that Australia imports productivity gains from the global frontier. A one per cent improvement in Australia’s economic globalisation score raises Australian labour productivity by around 0.3 per cent. Australia could enjoy labour productivity gains of up to nine per cent by matching the level of globalisation found in other economies. The report also provides a basis for estimating the labour productivity losses from any reversal in globalisation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. If Australia were to return to the level of economic globalisation prevailing in 1976, labour productivity would be around 12 per cent lower, holding other influences constant. Re-booting the globalisation of the Australian economy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic must be a priority for Australian policymakers.

Public policy should aim to place the Australian economy at the frontier of globalisation with a view to speeding convergence on US levels of productivity. Most notably, Increased foreign direct investment, freer digital commerce and increased immigration offer significant and underappreciated productivity benefits that require few changes in existing legislative or policy frameworks to capture. This contrasts with the more inwardly-focussed microeconomic housekeeping approach favoured by the Productivity Commission, which is particularly vulnerable to frustration by the processes of ordinary politics, and has seen little progress measured against the reform priorities advanced by Gary Banks in 2012. While domestic-oriented reform is no less worthwhile and may even have larger long-run payoffs, gains from further internationalisation are still worth pursuing, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 shock to globalisation.

Long-run trends in Australian and US living standards and productivity

The longest time series on relative living standards in Australia and the United States, going back to 1820, comes from the Maddison Project database.16 The Penn World Tables17 and The US Conference Board’s Total Economy Database18 also compile long-run and internationally comparable historical data on living standards and productivity. The ratio of Australian to US average living standards derived from these sources is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Ratio of Australian to US living standards

The era of ‘Australian exceptionalism’ in the second-half of the 19th century saw Australia enjoying an average standard of living around 40 per cent higher than the United States. Australia and the United States converged by around 1900, but Australian living standards declined in relative terms after the 1890s and during the era of de-globalisation from 1914-1945. For much of the post-World War Two period, Australia’s per capita income has ranged from around 70 to 90 per cent of the US level and currently sits at around 85 per cent. The terms of trade boom that peaked in 2011 narrowed the income gap (especially at market exchange rates) but did not eliminate it.

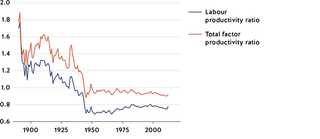

Given the importance of productivity as a driver of long-run living standards, it is not surprising to find that the productivity differential between Australia and the United States shows a similar historical pattern. The Bergeaud-Cette-Lecat (BCL) dataset provides one of the longest perspectives on relative productivity since 1890.19 Figure 2 shows labour and total factor productivity in Australia relative to the United States.

Figure 2. Australia-US productivity ratios

Australia enjoyed a level of productivity nearly twice as high as the United States in 1891, consistent with the earlier observation that wages in Sydney were around two times that found in Chicago and San Francisco. This productivity lead erodes during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the post-World War Two period, labour productivity has been less than 80 per cent of the US level while total factor productivity has been around 90 per cent of the US level, although cross-country comparisons of multifactor productivity can be unreliable. Australia showed stronger productivity growth than the United States between 1973 and 2000, narrowing the gap with the United States, but this trend has reversed since 2000.20 While the magnitude of the productivity gap varies across internationally comparable datasets, these trends in the gap is also evident in other measures.

As already noted, productivity differentials at the national level may reflect differences in the relative shares of different industries with different productivity levels in the overall economy. Industry-level comparisons of productivity are more meaningful than those at an economy-wide level, although the data at an industry-level are also less reliable. Differences in labour utilisation rates (total hours worked divided by population) will also affect productivity. The marginal worker is typically less productive than the average worker and so higher labour utilisation rates will weigh on productivity growth, although they are still of benefit to economic growth. Since the 2008 financial crisis, Australia has enjoyed higher rates of labour utilisation than the United States, which has been good for growth in average incomes, but has weighed on productivity. In the modelling that follows, increased labour utilisation is shown to lower Australian productivity growth, controlling for other factors.

As well as differences in industry composition, differences in economic geography may also be a structural impediment to narrowing the productivity gap with the United States. For example, as much as 40 per cent of the Australia-US productivity differential in the mid-2000s may have been attributable to Australia’s less-favourable economic geography. Yet as Battersby notes, ‘this imposes a condition on convergence with the productivity frontier but does not mean that the rate of growth is any lower than the frontier’s in the long-run.’21 Moreover, there has been a dramatic decline in global shipping costs in recent decades. Real ocean shipping costs fell by 50 per cent between 1974 and 2016. The real cost of air shipping declined by 78 per cent between 1970 and 2019.22 As the world’s centre of economic gravity moves closer to Australia and digital commerce assumes greater importance relative to trade in physical goods, the penalty imposed by geography should reduce over time.

Australia is only the 58th most economically globalised economy on one measure, just above the United States at 59th. But because the United States is on the frontier of global productivity, it is not as reliant as Australia on international connectedness for its productivity growth.

Given the structural differences between the Australian and US economies, Dolman et al have questioned the feasibility of closing the productivity gap with the United States at the aggregate as opposed to the industry level and argue this should not be a target for policy. At the same time, they recommend Australia can nonetheless aspire to at least narrow the gap.23 They note that much of the potential for Australia to catch-up with the United States resides at the industry rather than the national level. However, Australia’s integration with the rest of the world is likely to be an important driver of these industry-level changes in productivity.

How did Australia enjoy high levels of productivity in the second half of the 19th century? Part of the answer lies in the openness of the Australian economy and its integration with the rest of the world. As McLean notes, the Australian economy in the 19th century was more open than it was for much of the 20th century, with a trade share around 50 per cent of GDP.24 By contrast, Australia’s current trade share of around 40 per cent is one of the lowest in the OECD, leaving Australia as an outlier by being relatively closed for an economy of its size.25 As shown in Table 2 of this report, Australia is only the 58th most economically globalised economy on one measure, just above the United States at 59th. But because the United States is on the frontier of global productivity, it is not as reliant as Australia on international connectedness for its productivity growth.

Australia was also a globally significant destination for international capital flows in the 19th century. Foreigners, mainly from the United Kingdom, funded around 35 per cent of domestic investment on average between 1861 and 1889. According to Butlin, in the 1860s and 1880s it was around 50 per cent.26 As McLean notes ‘nothing comparable was to be attained during the second period of globalisation in the late 20th century with respect to Australia’s significance as a destination for international capital flows.’27 Today, Australia’s international financial integration ratio ranks only 17th on the MGI Financial Connectedness Ranking based on the US dollar sum of its foreign assets and liabilities.28

People flows were also important. At the time of the first countrywide census in 1891, Australia had a foreign-born share of the population of 32 per cent compared to 29 per cent in 2018, the highest in more than 120 years.29 Immigration contributed around 34 per cent of the expansion of the Australian population between 1861 and 1889, including the author’s three times grandparents in 1871. Australia accounted for seven per cent of migration flows from Europe between 1851 and 1915, less than the US share, but third overall and a higher share than Canada.30

The historical record suggests that Australian living standards and productivity do relatively well when Australia enjoys high levels of openness and integration with the world economy and during periods of increased globalisation. The de-globalisation period of 1914-1945 saw Australia’s living standards and productivity slip in relative terms. The re-internationalisation of the Australian economy in the 1980s and 1990s improved Australia’s economic performance and narrowed the gap with the United States, but convergence on the global productivity frontier occupied by the United States has remained elusive, in part because Australia’s economic globalisation remains relatively low.

Testing long-run convergence in Australian and US living standards

The prediction of economic theory that economies should in the long-run converge on a similar average living standard has a testable implication. Forecasts of per capita income differences should converge to zero in expected value as the forecast horizon becomes arbitrarily long, regardless of initial capital stock, at least for economies that are near their long-run equilibria and with similar technology and preferences.31 Convergence also implies that output shocks in one economy should be transmitted internationally, otherwise these shocks would persist infinitely. In practice, tests for convergence will often adjust for these country-specific shocks. In statistical terms, long-run convergence implies the absence of either a stochastic or deterministic trend in the (log) difference between Australian and US real income per capita.

In addition to long-run convergence in per capita incomes, the theory of economic growth also suggests the possibility of catch-up growth for economies that are out of long-run equilibrium, over a fixed period of time. Catch-up growth implies the absence of a stochastic, but not a deterministic, trend in the (log) per capita income differential. Oxley and Greasley, for example, find evidence of a historical catch-up relationship between Australian and US per capita incomes for the period 1882-1992, but not long-run convergence.32

In Appendix 1, I test the long-run convergence hypothesis for Australian and US per capita income differences using The Conference Board dataset. I confirm the absence of both a stochastic and deterministic trend in the income gap for the sample period 1952 to 2019. This is consistent with long-run convergence in per capita income between the two economies. Convergence in average living standards can be driven by a range of factors. Capital-deepening, increases in hours worked or employment and improvements in labour quality (human capital) could narrow the income gap, but increased productivity is a preferable source of growth in average living standards.

I also test for long-run convergence in Australian and US labour productivity levels. In this case, the results are not consistent with unconditional long-run convergence, pointing to structural differences between the two economies. However, subsequent modelling points to a long-run relationship conditional on other variables.

Explaining Australia’s recent productivity performance

Recent studies of the United States’ and Australia’s productivity performance have largely focused on the question of why productivity growth accelerated in the 1990s and then slowed again in the 2000s relative to a baseline trend rate of growth given by earlier decades.33 A wide-range of influences have been considered in the literature, but have mainly focused on proximate causes, without reaching definitive conclusions about the deeper determinants of productivity growth.

The reforms that (re)internationalised the Australian economy starting in 1983 have been widely credited for the productivity surge in the 1990s.34 Many of these reforms focused on opening-up the Australian economy, in particular, reductions in tariff protection and greater openness to foreign capital, which in turn increased export competitiveness. The liberalisation of merchandise trade alone between 1986 and 2016 is estimated to have raised Australia’s real GDP per capita by $3,506, representing a lower bound on the gains from broader liberalisation.35 The income gains from the terms of trade boom would have bypassed Australia were it not for increased openness to trade. The estimated 7.4 per cent increase in real wages due to merchandise trade liberalisation points to economy-wide productivity gains given the long-run relationship between productivity and compensation.36

Recent studies of the United States’ and Australia’s productivity performance have largely focused on the question of why productivity growth accelerated in the 1990s and then slowed again in the 2000s relative to a baseline trend rate of growth given by earlier decades.

Recent firm-level data shows that Australian exporters enjoy labour productivity 13.4 per cent higher than non-exporters and average wages 11.5 per cent higher.37 US productivity growth also accelerated in the 1990s and Australia’s opening-up enhanced the ability of its economy to share in this US trend. However, these reforms likely had one-off effects on the level of productivity, moving output closer to the efficient frontier, without necessarily shifting the frontier itself.38 Similarly, the absence of significant structural reforms since 2000 is consistent with the subsequent productivity slowdown.

The technology shock from the information and communications technology (ICT) revolution is also credited for the 1990’s productivity surge. Australia is one of the few advanced economies to generate significant productivity benefits from the use of ICT, accounting for around one-third of Australian labour productivity growth in the 1990s.39 Because Australia is a net consumer and importer of ICT equipment rather than a producer and exporter, the ICT revolution was experienced by Australia as a form of capital deepening. This contributed to labour productivity, as well as multifactor productivity from user-based innovations based on ICT. Australia was only able to capitalise on these labour productivity gains because of its openness to imports of ICT capital equipment, which facilitated a high take-up rate for new technology, as did product and labour market reforms. The declining relative price of imported ICT capital goods reduces the relative price of investment in Australia and induces capital accumulation, boosting productivity through capital deepening.40 Lower imported ICT prices also assist income growth through Australia’s terms of trade. Because the technology revolution is largely exogenous to the Australian economy, its benefits largely accrue via Australia’s openness to the rest of the world.

Inadequate investment in education and innovation is sometimes suggested as one cause of the productivity slowdown.41 Human capital formation and its contribution to the quality of labour inputs could explain recent productivity trends. However, the quality of labour inputs has generally been improving through both the 1990s and 2000s and labour quality has made a positive contribution to MFP growth.42 The education gap with the United States has closed in recent years so that ‘there is little reason to believe that differing levels of educational attainment are contributing to the present productivity gap with the United States.’43 Human capital formation does not explain the recent productivity slowdown.

As with ICT capital goods, Australia’s stock of human capital can be augmented through migration, especially skilled migration. For example, more than half of the increase in Australian graduate numbers since 2013 hold degrees from overseas universities or are non-citizen holders of Australian university degrees, implying nearly half of Australia’s human capital formation at the university degree level receives little or no assistance from Australian higher education policy.44 Migration also contributes to productivity growth through innovation (thought to be proportional to population),45 spurring new business formation through increased demand and generating efficiency gains through increased scale economies.

Migrants to Australia earn between three and five dollars per hour more than non-migrants, implying higher rates of productivity. Migrants account for around 0.17 percentage points of annual productivity growth and 0.1 percentage points of MFP growth between 2006 and 2011.46 The proportion of Australians born overseas is at its highest since the late 19th century at 29 per cent,47 suggesting migration is making a stronger contribution to both the quantity and quality of labour inputs.

The proportion of Australians born overseas is at its highest since the late 19th century at 29 per cent, suggesting migration is making a stronger contribution to both the quantity and quality of labour inputs.

Research and development (R&D) spending is also sometimes highlighted as a potential factor in slower productivity growth, but there is little or no support for this view in the case of advanced economies. As Crafts notes, ‘an obvious implication is that a simplistic solution of tackling the productivity slowdown with increased subsidies to R&D is unlikely to be successful.’48 In Australia’s case, changes in R&D spending do not have a clear relationship with productivity growth.49

The terms of trade boom from 2003-2011 contributed to a boom in mining investment, which dramatically increased the Australian capital stock and capital per worker. However, it also contributed to a slump in capital productivity, with a long lag before the increased investment turned into increased output. Capital deepening has improved labour productivity, but MFP growth during and after the terms of trade boom has been weak. Although led by the mining industry, weakness in MFP growth has also been broad-based, suggesting economy-wide factors are at work.50 The income gains from the terms of trade boom have somewhat masked weakness in productivity growth. As the terms of trade boom recedes, higher productivity growth will be necessary to sustain growth in incomes.

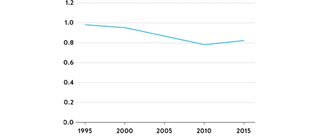

Growth in income from the terms of trade boom may have also masked the growing burden of regulatory accumulation on the Australian economy. While the absence of significant structural reform since 2000 has already been noted, creeping regulation could be expected to erode productivity growth, not least by restricting innovation. The growth in restrictive regulation in Australia relative to the United States has been documented by the Mercatus Center’s RegData project.51 Figure 3 shows the ratio of US to Australian regulatory restrictions on a per capita basis, suggesting an increasing relative burden on Australia over time which can be expected to hinder convergence with the United States.

Figure 3. Ratio of US to Australian regulatory restrictions per capita

In summary, the proximate causes of Australia’s productivity slowdown are readily apparent through the decomposition of income and productivity growth into their constituent components. However, there is less agreement on the deeper determinants of these trends. Past economic reforms made an important, but possibility transitory, contribution to productivity growth, while the growing burden of regulatory accumulation may be weighing on productivity growth in the absence of new reforms.

Globalisation of the Australian economy and productivity growth

The openness of the Australian economy has been essential to its ability to sustain productivity growth, in particular, through ICT capital goods imports and human capital through immigration. Trends in the openness and globalisation of the Australian economy may provide a unifying explanation for economy-wide productivity trends. These trends are captured by the KOF Globalisation Index, which measures globalisation across a number of dimensions. As well as openness to cross-border trade in goods and services, investment, migration and other people flows, the index captures measures of trade in intellectual property, the use of ICT and human capital accumulation. The index has been shown to have explanatory power for both per capita income and GDP growth in cross-country settings.52 The index for Australia is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. KOF Economic Globalisation Index for Australia

1 is least globalised, 100 is most globalised

Australia is ranked 25th globally on the headline index, with globalisation at a record high in 2017, while the United States is ranked 23rd with a slightly higher score. However, on the economic sub-index, Australia ranks only 58th and the United States 59th. Both countries show a similar trend on this measure over time. In a cross-country setting, globalisation and aggregate productivity need not be strongly correlated, given differences in industry composition, labour utilisation rates and other factors discussed previously, although there is cross-country evidence for trade openness explaining productivity.53

The relationship between the KOF Globalisation Index and the level of labour productivity for OECD countries for the year 2017 is shown in Figure 5. Australia is close to the line of best fit, but with levels of globalisation and productivity below some peer economies.

Figure 5. KOF Globalisation Index and labour productivity, 2017

At the country level, globalisation is expected to be a stronger driver of productivity outcomes over time. Australian productivity growth slowed around the year 2000, broadly coincident with a levelling out in the index compared to the rapid gains of previous decades. Note that because the index is bounded at 100 while labour productivity is unbounded, the gains in productivity associated with an increase in the value of the index may be one-time level effects rather than ongoing growth effects, as noted earlier with respect to the reforms of the 1980s and 1990s.

The long-run effect of the globalisation of the Australian economy can be examined in the context of a model of labour productivity (Appendix 2). Other variables in the model include US labour productivity, capturing the transmission of trends at the frontier of global productivity growth to Australia, as well as Australia’s labour utilisation rate and per capita capital stock to capture labour and capital inputs. The quality of labour inputs is captured by the KOF Globalisation Index, which includes a human capital index for Australia. As noted previously, much of Australia’s human capital is effectively imported. The model is consistent with the historical experience described earlier, in which trends in openness and globalisation seem to broadly correlate with the relative performance of Australian productivity and living standards.

Table 1 reports the results of a model that estimates the long-run responses of Australian labour productivity to a one per cent change in each of the KOF Economic Globalisation Index for Australia, US labour productivity, the per capita capital stock and labour utilisation rate for the period since 1971 when the KOF Globalisation Index begins.

Table 1. Long-run response of Australian labour productivity

|

KOF Economic Globalisation Index |

0.29*** |

|

US labour productivity |

0.95*** |

|

Labour utilisation |

-0.80*** |

|

Per capita capital stock |

0.30** |

|

|

|

|

Speed of adjustment |

-0.54 |

|

F-bounds test stat. |

6.11*** |

|

t-bounds test stat |

-4.77*** |

A one per cent increase in the KOF Economic Globalisation Index for Australia raises Australian labour productivity by nearly 0.3 per cent, while a one per cent increase in US labour productivity raises Australian productivity by 0.95 per cent. This suggests Australian labour productivity growth is broadly in line with that of the frontier, but that structural impediments have prevented closing the productivity gap with the United States. The labour utilisation rate has the negative effect on productivity predicted by economic theory, while the per capita capital stock (capturing capital intensity) raises labour productivity.

To put these results in perspective, Australia could enjoy a nine per cent gain in labour productivity by matching its level of globalisation to that of Singapore, a five per cent gain by matching Germany or the United Kingdom, and a 1.5 per cent gain by matching Canada. These potential productivity gains are shown in Table 2. The estimated gains assume other factors are held constant. They do not imply that matching the level of economic openness will lead to equivalent levels of labour productivity. Some countries with higher globalisation scores have lower labour productivity due to factors other than globalisation, such as poor governance.

Table 2. Globalisation and Australian productivity

|

Rank |

Country |

Economic globalisation, overall index |

Log-level deviation over Australia x 100 |

Australian labour productivity gain (per cent) from equivalent level on the index |

|

1 |

Singapore |

94.0 |

32.1 |

9.2 |

|

2 |

Netherlands |

88.7 |

26.3 |

7.5 |

|

3 |

Belgium |

88.5 |

26.1 |

7.5 |

|

4 |

Luxembourg |

88.3 |

25.9 |

7.4 |

|

5 |

Hong Kong, China |

88.2 |

25.8 |

7.4 |

|

6 |

Ireland |

88.0 |

25.5 |

7.3 |

|

7 |

Switzerland |

86.8 |

24.1 |

6.9 |

|

8 |

Malta |

86.5 |

23.8 |

6.8 |

|

9 |

Estonia |

86.3 |

23.5 |

6.8 |

|

10 |

United Arab Emirates |

85.9 |

23.2 |

6.7 |

|

11 |

Denmark |

84.5 |

21.4 |

6.1 |

|

12 |

Cyprus |

84.3 |

21.2 |

6.1 |

|

13 |

Czech Republic |

84.0 |

20.9 |

6.0 |

|

14 |

Sweden |

83.3 |

20.1 |

5.8 |

|

15 |

Slovak Republic |

83.1 |

19.8 |

5.7 |

|

16 |

Finland |

83.0 |

19.6 |

5.6 |

|

17 |

Austria |

82.9 |

19.5 |

5.6 |

|

18 |

Hungary |

82.7 |

19.3 |

5.5 |

|

19 |

Bahrain |

82.5 |

19.1 |

5.5 |

|

20 |

Mauritius |

82.2 |

18.7 |

5.4 |

|

21 |

Latvia |

82.1 |

18.6 |

5.3 |

|

22 |

Georgia |

82.0 |

18.5 |

5.3 |

|

23 |

United Kingdom |

81.5 |

17.8 |

5.1 |

|

24 |

Germany |

80.5 |

16.6 |

4.8 |

|

25 |

Portugal |

80.2 |

16.2 |

4.7 |

|

26 |

Lithuania |

79.6 |

15.5 |

4.4 |

|

27 |

France |

78.1 |

13.5 |

3.9 |

|

28 |

Montenegro |

78.1 |

13.5 |

3.9 |

|

29 |

Bulgaria |

77.8 |

13.2 |

3.8 |

|

30 |

Norway |

77.5 |

12.9 |

3.7 |

|

31 |

Slovenia |

77.3 |

12.5 |

3.6 |

|

32 |

Malaysia |

76.8 |

11.9 |

3.4 |

|

33 |

Spain |

76.6 |

11.6 |

3.3 |

|

34 |

Panama |

76.1 |

11.0 |

3.1 |

|

35 |

Qatar |

76.1 |

11.0 |

3.1 |

|

36 |

Croatia |

75.7 |

10.5 |

3.0 |

|

37 |

Seychelles |

74.8 |

9.3 |

2.7 |

|

38 |

Poland |

73.5 |

7.6 |

2.2 |

|

39 |

Serbia |

73.4 |

7.4 |

2.1 |

|

40 |

Greece |

72.9 |

6.7 |

1.9 |

|

41 |

Kuwait |

72.5 |

6.1 |

1.8 |

|

42 |

Micronesia, Fed. Sts. |

72.3 |

5.8 |

1.7 |

|

43 |

Canada |

71.7 |

5.1 |

1.5 |

|

44 |

Macedonia, FYR |

71.3 |

4.5 |

1.3 |

|

45 |

Romania |

71.0 |

4.1 |

1.2 |

|

46 |

Azerbaijan |

70.9 |

4.0 |

1.1 |

|

47 |

New Zealand |

70.3 |

3.0 |

0.9 |

|

48 |

Italy |

70.2 |

2.9 |

0.8 |

|

49 |

Chile |

70.2 |

2.9 |

0.8 |

|

50 |

Israel |

69.9 |

2.5 |

0.7 |

|

51 |

Albania |

69.9 |

2.5 |

0.7 |

|

52 |

Armenia |

69.5 |

1.9 |

0.6 |

|

53 |

Kiribati |

69.2 |

1.6 |

0.4 |

|

54 |

Iceland |

69.2 |

1.5 |

0.4 |

|

55 |

Jordan |

69.0 |

1.3 |

0.4 |

|

56 |

Lebanon |

69.0 |

1.2 |

0.3 |

|

57 |

Antigua and Barbuda |

68.6 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

|

58 |

Australia |

68.2 |

NA |

NA |

|

59 |

United States |

68.1 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

While Australia may struggle to attain the level of global integration of small European economies or an entrepot economy like Singapore, it has the potential to increase its integration with the world economy in ways that are likely to enhance productivity based on the long-run relationship between economic globalisation and labour productivity.

Many of the policies that determine Australia’s relative openness are amenable to change within the framework of existing legislation, unlike the ambitious microeconomic reform agenda favoured by the Productivity Commission. Increased globalisation may provide governments with increased leverage over domestic interest groups opposed to reform by exposing the Australian economy to increased competitive pressures from abroad.

At the same time, it should be recognised that increased globalisation may increase the exposure of the Australian economy to foreign-sourced shocks, both positive and negative. The COVID-19 pandemic is just one obvious example of a foreign shock transmitted directly to Australia through trade linkages and people flows. Some of my other research suggests that federal legislative activism in Australia responds positively to negative economic shocks, although that research did not distinguish between domestic and foreign-sourced economic shocks.54 Increased globalisation may result in an increased burden of taxation and regulation designed to moderate the impact of foreign economic shocks. This in turn may give rise to long-term cycles in globalisation and productivity such as those experienced by the Australian economy. Yet the results reported above suggest globalisation is a positive for productivity in the long run.

Policy recommendations: Reducing barriers to globalisation

The robust role of a measure of globalisation in explaining Australian productivity suggests an ongoing role for increased openness in driving productivity growth. The Productivity Commission has made useful recommendations for reductions in barriers to international trade, but the focus for much of its reform agenda has turned inward and there has been little progress on many of the reforms advocated by the Commission. The political process is no longer seen as strongly reform-oriented, in part because of the difficulty of progressing reforms in the face of domestic opposition.

Yet the federal government retains considerable leverage over the openness of the Australian economy within the framework of existing legislation and policy. Australia could improve its performance on measures of globalisation to be more consistent with other small open economies that typically enjoy high levels of productivity. Australia could also improve its openness relative to an increasingly inward-looking United States, helping to narrow the productivity differential. Several areas of reform suggest themselves.

Recover pre-COVID-19 levels of economic integration: the most urgent task facing Australian policymakers is to restore Australia’s integration with the world economy in the wake of the pandemic.

Lower barriers to foreign direct investment: Foreign direct investment (FDI) has long been recognised as a driver of productivity through knowledge spillovers and capital deepening. As Quiggin notes, ‘further capital deepening could be achieved by encouraging foreign investment.’55 Yet Australia remains a relatively restrictive jurisdiction for FDI by OECD standards and has imposed a growing thicket of regulation and taxes on FDI inflows. My report with Jared Mondschein suggests ways of improving the regulation of FDI with a view to increasing cross-border investment.56

The most urgent task facing Australian policymakers is to restore Australia’s integration with the world economy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lower barriers to digital trade: Australia has relatively high barriers to digital commerce.57 Australia should aim to lower these barriers and join New Zealand, Chile and Singapore in the plurilateral Digital Economic Partnership Agreement. Australia should also shelve plans for a unilateral digital services tax in favour of a multilateral framework.

Lower barriers to services trade: The Productivity Commission has made useful recommendations in relation to lowering barriers to services exports, with priority areas of financial services, air services, visa processing and infrastructure.58 However, gains from trade are also attainable in relation to lowering barriers to services imports.

Reverse the recent reduction in the permanent migration intake: migrants enjoy higher levels of productivity than non-migrants and contribute positively to labour and multifactor productivity growth. Around half of Australia’s human capital formation at the degree level already occurs through migration at little cost to taxpayers. This is in contrast to efforts to promote human capital formation via other policies. In the wake of the pandemic, restoring net overseas migration should be a priority.

Reduce economic policy uncertainty: policy uncertainty is an implicit trade barrier. As my previous report on economic policy uncertainty demonstrates, reducing political uncertainty can be expected to benefit international trade and investment.59

Conclusion

Australia once enjoyed the highest standard of living and world-beating productivity well in excess of the United States. This performance coincided with a very high level of economic integration with the rest of the world and a rapidly globalising world economy during what became known as the first era of globalisation.

A disastrous inward turn around the time of Federation in 1901, followed by a period of de-globalisation from 1914-45 saw Australia’s relative living standards and productivity slip, particularly compared to the United States. The re-internationalisation of the Australian economy from 1983 enabled Australia to narrow some of the gap with the United States that emerged in the post-World War Two period, but closing the gap with the global frontier now represented by the United States has so far eluded Australian policymakers.

A renewed focus on further internationalising the Australian economy is potentially a powerful lever to combat the productivity slowdown and advance Australia to the frontier of global productivity and living standards, recovering the exceptionalism of the late 19th century.

There is no reason in-principle why Australia should not be able to significantly narrow, if not close, the income and productivity gap with the United States. While structural differences with the US economy such as industry composition, labour market participation and geography may preclude closing the productivity gap at an aggregate level, there is still scope for greater convergence at an industry level.

Australia’s income and productivity growth is broadly correlated with trends in economic openness and globalisation. The terms of trade boom would have meant little to Australia were it not for the increased openness to international trade and investment that preceded it.

Based on historical relationships, Australia could enjoy labour productivity gains of up to nine per cent by positioning itself at the frontier of international economic openness. Policymakers can in many cases increase the openness of the Australian economy within the framework of existing legislation and policy. While the Productivity Commission continues to make useful recommendations for reform, many of its proposed reforms are inward-looking and subject to frustration by the processes of ordinary politics and little progress has been made on the reform agenda advocated by Gary Banks in 2012. A renewed focus on further internationalising the Australian economy is potentially a powerful lever to combat the productivity slowdown and advance Australia to the frontier of global productivity and living standards, recovering the exceptionalism of the late 19th century. Re-booting Australia’s economic integration with the rest of the world will be particularly important in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Appendix 1

Tests for long-run convergence in Australian and US living standards and productivity

Following Oxley and Greasley (1995), I perform unit root tests which allow for structural breaks in the trend process on the Australia-US per capita income and labour productivity differentials using The Conference Board dataset in the case of the income differential and the OECD current purchasing power parity measures in the case of the labour productivity differential. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Unit root tests for Australia-US income and productivity differentials

|

Dep. var. |

ADF t-stat |

Trend term |

Break year in trend process |

|

Aus-US income/capita |

-5.15** |

0.00 |

1982 |

|

Aus-US labour prod. |

-4.10 |

0.00 |

1984 |

The ADF t-statistics are for the null hypothesis of a unit root in the differential, while the associated p-values are based on the non-standard critical values for the rejection of this hypothesis. The test statistics indicate a stochastic trend is absent in the case of the income differential, but cannot be ruled out in case of the labour productivity differential.

The trend term and associated p-value tests for the value and statistical significance of a deterministic trend in the differential. The trend term is estimated to be equal to zero. The break year is found to be 1982 in the income differential and 1984 in the labour productivity differential. The break years coincide with the onset of the reform era from 1983. The break terms are statistically significant in the case of the income differential, but not the productivity differential.

The test statistics are consistent with long-run convergence in the income differential, but not the labour productivity differential. As noted in the text, economic theory predicts unconditional long-run convergence in the case of the income differential, but not necessarily the productivity differential. However, the results in Appendix 2 point to a long-run relationship between Australian and US productivity conditional on other variables not included in the above analysis.

Appendix 2

A model of Australian labour productivity growth

I estimate an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model based on the following variables: the log of Australian labour productivity (lp) in current price purchasing power parity terms, the log of Australian labour utilisation (measured as total hours worked divided population) (lu), the log of the KOF Economic Globalisation Index for Australia (kofgi), the log of US labour productivity (uslp) in current price purchasing power parity terms and the log of Australian per capita capital stock (kpc). The model includes an unrestricted constant and trend term. Lag order is chosen by minimising the Schwarz criterion up to a maximum lag of three years for both the dependent and independent variables.

The levels equation recovered from the conditional error correction form of the model is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Long-run response of Australian labour productivity

|

KOF Economic Globalisation Index |

0.29*** |

|

US labour productivity |

0.95*** |

|

Labour utilisation |

-0.80*** |

|

Per capita capital stock |

0.30** |

|

|

|

|

Speed of adjustment |

-0.54 |

|

F-bounds test stat. |

6.11*** |

|

t-bounds test stat |

-4.77*** |