This is the first in a series by Lesley Russell on why the impact of COVID-19 is worse on certain groups.

The coronavirus pandemic has dramatically highlighted the divisions, inequities and inequalities in even the wealthiest societies.

The likelihood of contracting coronavirus and the severity of the illness it causes are both governed by people’s pre-existing health status. Age and medical problems such as obesity, heart disease, diabetes and respiratory conditions are significant risk factors.

But as the pandemic shines a merciless light on the gaps in the social safety net, healthcare experts are recognising the impact of the social determinants of health. Poverty, housing, education, environment, safe workplaces and discrimination that affects an individual’s ability to achieve health and wellness are factors influencing the outcomes of COVID-19 and the measures used to prevent infection.

These factors increase the risks for coronavirus in racial minority and First Nations communities. This is aggravated if access to affordable healthcare services is not available.

Linked health and socioeconomic disparities in the United States

In the United States, African Americans, Native Americans and Alaska Natives fare significantly worse than white Americans across most health status indicators and Hispanics also face large disparities for certain measures. Disparities in HIV/AIDS diagnosis and overall death rates are particularly striking for African Americans, Hispanics, and First Nations people.

All racial and ethnic groups, and especially Hispanics and African Americans, experienced improvements in health coverage, access, and utilisation as a consequence of the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as Obamacare. The efforts of the Trump Administration and Republican-controlled states to claw back many of the provisions of the ACA, especially Medicaid expansion, have meant many have now lost these health insurance benefits.

In the United States, African Americans, Native Americans and Alaska Natives fare significantly worse than white Americans across most health status indicators and Hispanics also face large disparities for certain measures.

The Indian Health Service provides government medical care to 2.5 million of the nation’s 5.2 million American Indians and Alaska Natives but it is widely judged to provide substandard care and problems are pervasive. Indian Health Service hospitals have only 625 beds nationwide, with six intensive care units and ten ventilators. Some tribes provide additional healthcare services in their communities and these supply another 772 beds, but that is just 1,397 beds for 2.5 million people.

Funding and workforce shortages are continuing problems. Tribal members who seek treatment outside the system must petition for reimbursement from the Indian Health Service, which does not have sufficient funds to pay for the private care of all those who need it.

Additionally, for many people in minority populations, employment opportunities are few and involve low or hourly wages and irregular hours, low levels of occupational health and safety, and few benefits such as paid sick leave and family leave. This means workers cannot afford to take time off work and it is difficult to self-isolate when they or family are ill. A recent report from the Pew Research Center found that Hispanics have been hardest hit financially by the pandemic, through pay cuts and lost jobs.

Many Native American tribes get their income from tourism and casinos, most of which are now shut down. The National Indian Gaming Association has asked Congress for at least US$18 billion in federal aid over six months to address shortfalls in income from closing casinos, which many tribes depend on.

Linked health and socioeconomic disparities in Australia

In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience much greater mortality and burden from chronic disease than non-Indigenous Australians. Key determinants of Indigenous health inequality include the lack of equal access to healthcare and the lower standard of health infrastructure, including housing, healthy food, education, transportation, in Indigenous communities compared to other Australians.

Under the Closing the Gap initiative, all Australian governments have committed to improving the lives of Indigenous Australians, but progress to date has been very slow and variable. The seven current targets focus on health, education and employment but there is a push to have additional targets included in the Closing the Gap Refresh, including a target that Indigenous people are not over-represented in the criminal justice system.

Many Indigenous Australians get their primary care through Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations which are initiated and operated by local Indigenous communities. There are 143 Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations operating more than 300 clinics across Australia, delivering holistic, comprehensive and culturally competent primary healthcare services. They provide about three million episodes of care each year for about 350,000 people. However, despite their recognised value, more resources are needed to ensure outreach to more remote communities and the availability of needed healthcare professionals.

The numbers tell the story: The burden of coronavirus mortality and morbidity falls unequally on racial minorities in the United States

There is a disproportionate burden of illness and death from coronavirus among racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States. While most of the focus has been on the impact on African Americans, this burden extends to Hispanics and Native Americans, although there are fewer data to support this.

Frustratingly, although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) routinely collects and publishes national health data by race, it has only very recently begun to do this for coronavirus and what is available is far from complete. A full national picture of the racial impact is clouded by uneven reporting across states and counties, and in many places racial data for a large percentage of patients is unavailable.

Current CDC data show that, among COVID-19 deaths for which race and ethnicity data were available, death rates among African Americans (92.3 deaths per 100,000 population) and Hispanics (74.3) were substantially higher than that of white Americans (45.2) or Asian Americans (34.5).

Current CDC data show that, among COVID-19 deaths for which race and ethnicity data were available, death rates among African Americans (92.3 deaths per 100,000 population) and Hispanics (74.3) were substantially higher than that of white Americans (45.2) or Asian Americans (34.5).

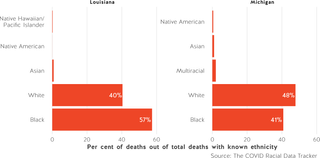

The New York Times provides data by state that is updated daily and for some states, the racial breakdowns are included (although these are not updated so often). At the beginning of May, in Louisiana, where about one-third of residents are black, 58 per cent of coronavirus deaths were African American. In Michigan, where less than 15 per cent of residents are African American, they make up about 40 per cent of those who died. And in South Dakota, where 81 per cent of residents are white, they make up only 32 per cent of coronavirus patients.

The COVID Tracking Project, based out of The Atlantic, has released a racial data tracker of COVID-19 cases and deaths by race and ethnicity. The data suffer from an inconsistent reporting system across states. The data set is updated several times daily. As of early May, out of all deaths with known ethnicity, 58 per cent in Louisiana were African Americans. Likewise, in Michigan, nearly 41 per cent of the state’s deaths from COVID-19 were African Americans.

The disparities are stark in the numbers that are emerging from areas hardest hit by the pandemic, especially in cities such as New York, Chicago and Washington DC which have large African American populations.

Race-specific data released by New York City on April 30 show that although African Americans make up 22 per cent of the population of the city, they represent 35.4 per cent of hospitalised cases and 30.5 per cent of the deaths from COVID-19. In Chicago, the situation is much worse. African Americans are dying at nearly six times the rate of white Americans. In Milwaukee the coronavirus has erupted in the city’s black community; a report from early April found African Americans in Milwaukee County made up almost half the county’s 954 cases and 81 per cent of its 27 deaths. In Maryland, the virus is described as ‘‘ravaging” Prince George’s County, one of the richest black counties.

States by state comparison of COVID-19 rates in the United States by race and ethnicity

The Hispanic population is also hard hit and there are concerns that official statistics may be underestimating the virus’ toll on these communities where people are wary of seeking medical care due to a lack of health insurance. Some of these communities have significant numbers of undocumented immigrants and they are fearful that going to a hospital will expose them to immigration authorities.

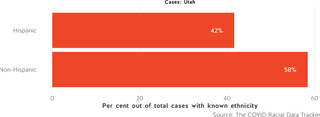

New York City data has shown that COVID-19 is killing Hispanic people at 1.6 times the rate that it is killing white Americans and in adjacent New Jersey, where Hispanics make up 19 per cent of the population, they account for 30 per cent of hospitalised patients. Even in states with relatively small Hispanic populations like Utah, they make up more than a third of COVID-19 cases.

Researchers are exploring why this toll is so appalling. There are obvious factors such as higher obesity rates (among American adults, 38.4 per cent of African Americans, 32.6 per cent of Hispanics and 28.6 per cent of white Americans are obese), large numbers of people without health insurance (19 per cent of Hispanics and 11.5 per cent of African Americans compared to 7.5 per cent of white Americans in 2018 — these figures would be higher now), and the fact that these population groups are overly represented in lower-paid and more hazardous jobs (such as caregivers, cashiers, sanitation workers, farmworkers and public transit employees).

Increasingly high blood pressure is seen as a major risk factor for COVID-19 severity and complications. The prevalence of high blood pressure or hypertension in African Americans is among the highest in the world; more than 40 per cent have high blood pressure which develops earlier in life and is usually more severe than for other Americans. Hispanic adults also have some of the highest prevalence of poorly-controlled blood pressure compared with any other race-ethnic group in the United States.

But there are also issues that relate to discrimination. There is substantial evidence that people of colour face explicit biases from healthcare professionals and that affects willingness of those who are sick to seek care, the quality of care they receive and their health outcomes. Even though Immigration and Customs Enforcement has said it won’t arrest undocumented immigrants seeking medical care during the pandemic, fear is a powerful factor preventing immigrants — especially those who are undocumented — from seeking testing and care.

Fears that coronavirus could decimate First Nations people

Infectious diseases have played a tragic role in the history of indigenous people in the Americas, from smallpox to the measles wiping out large swaths of the population through the centuries. In the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic and during the 2009 H1N1 flu epidemic, the death rate for Native Americans was four to five times higher than the nation as a whole. In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people made up 11 per cent of identified cases, 20 per cent of hospitalisations and 13 per cent of deaths, despite constituting only two per cent of the population.

On 30 April there were 2,711 confirmed coronavirus cases in the US Indian Health Service system, and 89 deaths according to an Indian Country Today database (likely more up to date than CDC numbers). Those numbers do not capture the large Native American population living off reservations. The United States has 574 federally recognised tribes, of which 229 are in Alaska.

In the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic and during the 2009 H1N1 flu epidemic, the death rate for Native Americans was four to five times higher than the nation as a whole.

Most of these infections (2,153) and deaths (62) are in the Navajo Nation, which sprawls across three states (Arizona, New Mexico and Utah). This is the third-highest per capita infection rate in the country, behind those of New York and New Jersey but ahead of Washington DC and ten times that of neighbouring Arizona. The Navajo Nation is approximately the same geographic area as West Virginia but it has only 12 healthcare facilities, 170 hospital beds, very few ICU beds and 28 ventilators. It has among the worst scores on the CDC Social Vulnerability Index. Thirty-nine per cent of residents live in poverty, there is a shortage of adequate housing and more than 30 per cent of households lack a toilet or running water.

Other tribal lands battling the pandemic include Washington state tribes (30 cases, 1 death), the Tohono O’odham Nation in New Mexico (28 cases, 3 deaths), the Cherokee Nation (64 cases, 3 deaths) and the Choctaw Nation (67 cases, 4 deaths) in Oklahoma, and the Mississippi Choctaw Nation (40 cases, 1 death).

It is very difficult to find data about the impact of coronavirus on Alaska’s First Nations people. CDC subsumes the statistics in with those of Native Americans. On 1 May, Alaska had recorded 364 cases and nine deaths (most of these in Anchorage) and it appears that while some of these were outside the main towns, none were Native Alaskans. Leaders acted promptly in Alaska’s remote villages and have imposed strict isolation rules, effectively cutting themselves off from the rest of the world. The villages have clinics, but residents must travel to regional hubs or farther for serious medical issues.

In Australia, Indigenous communities were able to get out in front of the epidemic

While only about 20 per cent of Indigenous Australians live in remote communities, they have been a primary concern. The coronavirus would wreak havoc in these communities where health status is poor with a high incidence of chronic diseases, housing and sanitary conditions are substandard, and healthcare services are in short supply.

As in Alaska, isolation is both a plus and a minus for these communities. It helps to keep the virus at bay but should it arrive, the combination of poor health, poor living conditions and the fact that hospital services are often a plane ride away will spell disaster. As in Alaska, Indigenous Australian community leaders have stepped in to take control, educate community members and, with the support of state and territory authorities, impose strict quarantine rules. These steps have apparently been effective in limiting the spread of the coronavirus to these Australian communities.

As early as January, the Apunipima Cape York Health Council, which delivers primary health to Cape York communities, began assembling the weaponry to respond to the threat, using advice from First Nations contacts in Canada and experience from the H1N1 flu pandemic.

Conclusion

Dr Tom Frieden, former director of the CDC, was recently quoted as saying in reference to the coronavirus pandemic, “Most epidemics are guided missiles attacking those who are poor, disenfranchised, have underlying health problems.” This is clearly exemplified in how the pandemic has impacted marginalised racial and ethnic minorities and First Nations people.

As George Packer wrote recently in The Atlantic, the coronavirus has revealed what is broken in American society and has exploited these conditions ruthlessly. Australia has thus far escaped the ravages experienced by the United States, but cannot afford smugness or complacency in this regard. In the conversations that have already begun about what the world will be like and the reforms needed post-pandemic, the physical, mental and social justice needs of the most marginalised individuals and communities must be included.

Data visualisation created by Zoe Meers.