It has been just six months since the new coronavirus officially known as SARS-CoV-2 was recognised and already it is the deadliest pandemic since the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) emerged forty years ago. This new pandemic has many intersections with HIV and disproportionately affects many of the same population groups. What are the lessons to be learned from HIV/AIDS and are these being effectively implemented in today’s fight against coronavirus? These lessons are particularly important if the search for a vaccine against coronavirus is as vexing and slow as that for a vaccine against HIV.

Two new viral pandemics

HIV and coronavirus are very different structurally, in how they infect the body, and in their disease profile. However, they share some things in common, most particularly in the way they suddenly emerged in the United States as a consequence of international travel and how they quickly spread around the globe and became a pandemic. The similar public response to these factors is striking.

When they hit the news headlines in 1981 and 2020, these were considered new viruses - although it now appears that both HIV and coronavirus had been around, unseen and unsuspected, for some considerable time before their presence was detected. Epidemiologists needed time to research how they spread, medical specialists needed time to assess the best treatments, public health officials needed time to assess the best prevention approaches, and politicians and their expert advisors needed practice in how to convey their messages and information to the public.

The viruses are alike in that they both have a long and often asymptomatic incubation period when people can be infectious and not realise it. This makes it more difficult to persuade people to follow public health guidelines.

The viruses are alike in that they both have a long and often asymptomatic incubation period when people can be infectious and not realise it. This makes it more difficult to persuade people to follow public health guidelines. It also means that testing is the only way the spread of the infection can be tracked, and efforts targeted at population groups and geographical areas in proportion to their need.

In the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and currently for coronavirus, self-isolation proved to be the only way to break the chain of infection. At this stage, there is no vaccine against either virus, but effective antiretroviral therapies (ART) have emerged to treat AIDS and reduce the HIV viral load such that infected people can now lead a normal lifestyle and have a close-to-average life expectancy. Additionally, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PreP), which also uses anti-viral drugs, can prevent HIV infection.

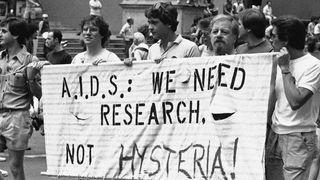

Coronavirus has little of the social stigma associated with early cases of HIV/AIDS and is still present at reduced levels today – though there are reportedly cases of bias-fuelled attacks against Asian Americans. A key difficulty in engaging politicians, policymakers and the public on HIV/AIDS was that it was seen as a lifestyle disease among gay men and drug addicts. It was initially called gay-related immune deficiency (GRID) disease and colloquially referred to as the “gay plague”. The renaming by President Trump and others of coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” or “kung flu” is as damaging as was the stigma and fear of gay men that was created in the 1980s.

Many of the initial victims of coronavirus were those who travelled internationally, cruised the oceans, skied at posh resorts and attended celebrity functions. But now the hardest hit are those who have the least protections in society – the homeless, prisoners, people of colour, immigrant workers, the frail elderly in nursing homes – and people in the areas of the United States where health status is already poor and health care services are few.

This largely reflects what happened with HIV.

The risks to people living with HIV from coronavirus

There is currently no evidence that people living with HIV are at increased risk of infection or complications from coronavirus if their infection is well controlled (ie where the virus is clinically and immunologically stable on antiretroviral therapies). There are reports on outcomes for patients with coronavirus and HIV co-infection from a number of countries, including the United States, that support this.

However, this does not hold for people with advanced AIDS, a low CD4 count (a measure of the strength of a person’s immune system), a high viral load or who are not taking antiretroviral therapies (ART). Also, there are many people in the United States living with HIV who are now in their sixties or seventies and have other co-morbidities such as diabetes or hypertension that are known to raise the risks from coronavirus, even if their HIV viral load is well controlled.

The coronavirus pandemic has already been observed to interrupt the continuum of care (testing, prophylaxis, treatment) for people living with HIV/AIDS, especially in places where health care services are already fragile. This can pose a real risk to their continuing health status.

The coronavirus pandemic has already been observed to interrupt the continuum of care (testing, prophylaxis, treatment) for people living with HIV/AIDS, especially in places where health care services are already fragile. This can pose a real risk to their continuing health status.

There are several population groups of people living with HIV who are both unlikely to have their infection well-controlled and are particularly exposed to coronavirus: these include prisoners, the homeless and poor Black and Hispanic Americans. The rate of HIV among prisoners in the United States is five to seven times that in the general population and prisons and jails have proven to be petri dishes for coronavirus infections. Additionally, African Americans and Hispanics who are at increased risk from coronavirus, are over-represented in the prison population.

In 2019, there were an estimated 11,000 homeless people with HIV/AIDS and, again, people of colour are over-represented in this population. Coronavirus is spreading “under the radar” in American homeless shelters where conditions are cramped and hygiene is often poor. Homelessness is a substantial barrier to consistent, recommended HIV care and access and adherence to ART, thus increasing the risk for illness and transmission.

The possibility emerges that those people living with HIV and on ART drugs such as the combination of lopinavir and ritonavir may gain a protective effect from the virus. However, there’s a paucity of data to support this. There are a number of trials underway investigating the efficacy of HIV protease inhibitors including lopinavir/ritonavir (marketed as Kaletra) against COVID-19. The sole published study to date failed to show a benefit in people with severe COVID-19. There are mixed findings for the association of lopinavir/ritonavir with a shortening of the time patients shed coronavirus.

How the spread of HIV and coronavirus are increasingly coincident

Even as robust health campaigns have led to downward trends in HIV diagnoses in the large American cities such as New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco and Chicago that have always been the foci of infections, in much of rural America an opposite trend is emerging.

There are an estimated 1.1 million people in the United States living with HIV and about 14 per cent of these are unaware they are infected. The decline in new infections has levelled off since 2013; something the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) attributes to problems in getting prevention, testing and treatment services to people who need them. This is especially true in rural areas and for African Americans and Hispanics.

Like HIV, coronavirus is moving inexorably from the cities of the northeast and the West Coasts to the poor southern states and the rural towns of the Midwest.

In 2018, ten states (California, Nevada, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, New York) and the District of Columbia had HIV infection rates greater than 14 cases for 100,000 people (the national average was 13.6 for 100,000 people — these data from the CDC are the most recent available). Southern states now account for more than half of all new cases of HIV/AIDS that are diagnosed, with the highest rates in Georgia, Louisiana and Florida, and 46 per cent of people living with HIV are in southern states. Most of these are people of colour and the percentage of people unaware they are infected is higher than the national average. Florida has a particularly severe problem: Miami has higher rates of HIV infection than San Francisco, New York City and Los Angeles.

Like HIV, coronavirus is moving inexorably from the cities of the northeast and the west coasts to the poor southern states and the rural towns of the Midwest. Last week saw spiking increases in new cases in Texas, South Carolina, Florida, California, Nevada, Arizona, Georgia, Utah and Oklahoma; with each of these states recording highs in their seven-day rolling totals. There are also increasing numbers of cases in Louisiana and Alabama. While the big cities like New York, Washington DC, Los Angeles and Chicago have seen huge numbers of cases, on a per capita basis, many places with the highest infection rates are rural communities in these states. Many of these hotspots are linked to the nearby presence of prison facilities and large food processing plants.

Political responses: Reagan vs Trump

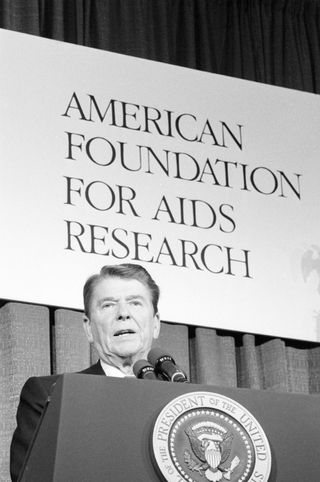

President Trump’s willful disregard of scientific advice on coronavirus echoes the behaviour of President Reagan towards HIV/AIDS. Like Trump, Reagan ignored early warnings of the threat from a new virus; in fact, he didn’t mention AIDS in public until 1985 (after the Hollywood actor Rock Hudson had announced he had AIDS).

In April the following year, with virtually no mention made in the interim, Reagan delivered his first major speech on AIDS to a meeting of the College of Physicians, calling it “public enemy number one”. In that same year, the United States shut its doors to HIV-infected immigrants and travellers.

Despite reports from the Surgeon General C Everett Koop and the Institute of Medicine in October 1986 that both called for nationwide educational and public health campaigns and voluntary testing, it was not until November 1988 that the National Commission in AIDS to advise the president and the Congress was established and not until 1990 that the Ryan White Care Act to provide federal funding for treatment and early intervention services was signed into law.

Reagan was criticised for his lack of leadership and for “refusing to acknowledge the lethal spread of AIDS across the nation”. Trump’s “deadly lack of leadership” on coronavirus is seen as damaging Americans’ health, the nation’s economy and its international standing.

Reagan was criticised for his lack of leadership and for “refusing to acknowledge the lethal spread of AIDS across the nation”. Trump’s “deadly lack of leadership” on coronavirus is seen as damaging Americans’ health, the nation’s economy and its international standing.

The first year of Trump’s presidency offered little hope that he would pay any positive attention to addressing HIV/AIDS at home or abroad. In 2017, the post of Director of National HIV/AIDS Strategy became vacant and has not been filled since and all the members of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS either resigned or were fired. This advisory work now continues under the direction of the Assistant Secretary for Health and the Director of HIV.gov.

Yet, Trump has shown some leadership in addressing the HIV epidemic in the United States, even as he attempts to dramatically reduce American efforts internationally. This apparently was driven from behind the scenes by Dr Anthony Fauci from the National Institutes of Health and Dr Robert Redfield, the Director of the CDC. People were surprised when President Trump talked about this in his February 2019 State of the Union speech, announcing the goal of ending the HIV epidemic in the United States within ten years, and even more surprised when his 63-word statement was actioned, along with funding authorised and appropriated by the Congress.

Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America (EHE) is initially focused on improving diagnosis, treatment and prevention efforts in geographic hotspots in states like Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia, Texas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Florida and South Carolina as well as California, New York and the District of Columbia. Between them, these counties and states account for more than half of the nearly 40,000 new HIV diagnoses each year. The goal is a 75 per cent reduction in new HIV infections within five years, and at least a 90 per cent reduction within ten years, for an estimated 250,000 total HIV infections averted. The CDC has stated how accelerated efforts are needed to achieve these goals.

In the FY2020 budget appropriations, the Congress provided US$241 million for EHE (it’s interesting to note that US$25 million requested for the Indian Health Service EHE activities was not appropriated). The funding tracker run by the Kaiser Family Foundation indicates to date just $15 million of these funds have been distributed. The President’s FY2021 Budget requests $761 million for the second year of this initiative.

Public health responses: the same experts for HIV and coronavirus

The three most prominent public health leaders on coronavirus — Dr Anthony Fauci, Dr Deborah Birx and Dr Redfield — all have backgrounds in HIV/AIDS.

Anthony Fauci, an immunologist, has been the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases since 1984 and has played a seminal role in advising political leaders and governments on managing the threats from infectious diseases over several decades. Deborah Birx was a military doctor specialising in HIV and later became the United States Global AIDS coordinator. She now serves as the response coordinator for the White House Coronavirus task force (which may or may not still be operative). Robert Redfield is also a former military doctor and a prominent AIDS researcher.

They have seen up close the damage done by poor political leadership and by baseless promises of a vaccine to eliminate the virus — a promise yet to be fulfilled for AIDS even after four decades. In the case of HIV/AIDS, they have also seen how united (and often angry) community voices served to drive needed actions from researchers, healthcare providers, pharmaceutical companies and legislators. Sadly today, most of the voices raised are in opposition to public health attempts to control the spread of coronavirus and around fears about any vaccine that might be developed.

Common barriers to testing and treatment for HIV and coronavirus

Just like HIV/AIDS, coronavirus has served to highlight the inequalities and racial discrimination that divide the United States and the huge gaps in healthcare services.

Many people who have been diagnosed as HIV positive are not getting the care needed, a situation that has worsened since 2015, presumably due to attacks from the Trump Administration and Republican state legislatures on Medicaid which is the major source of health care coverage for this population. Currently, it is estimated that 67 per cent of people who are positive get some form of HIV medical care (down from 73 per cent in 2015), but only about half of these get ongoing care and only 53 per cent have a suppressed viral load.

In 2018 only 18 per cent of the estimated 1.2 million persons who are considered at high risk for contracting HIV and thus indicated for use of PrEP were prescribed it. PrEP medications are very costly and are not widely available in rural areas. Low rates of uptake and availability are most pronounced in the hardest-hit southern states. These issues will be addressed to some extent by the Ready, Set, PreP program that is part of EHE but the program will reportedly reach only about 4,250 individuals within the first six months, a fraction of those who could benefit.

The costs of testing and treatment (and then the loss of income from self-isolation) are deterring many people from being tested or seeking medical care if they develop COVID-19 symptoms or believe they have been exposed to coronavirus.

Similarly, the costs of testing and treatment (and then the loss of income from self-isolation) are deterring many people from being tested or seeking medical care if they develop COVID-19 symptoms or believe they have been exposed to coronavirus. The situation will worsen as it is estimated that up to 43 million Americans could lose their health insurance as a result of the economic impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. That likelihood has not stopped the Trump Administration from continuing efforts to abolish Obamacare.

As both viruses spread to rural areas, the inadequacies of rural health care services are exposed. In many places, the local healthcare system is already stretched thin and coronavirus has overwhelmed small hospitals that often lack intensive care units and ventilators.

Small rural health jurisdictions generally lack the resources and expertise to confront HIV/AIDS. Lack of transportation and stigma are seen as the biggest barriers to testing and care; people living in large cities can get tested and treated while feeling relatively anonymous in a clinic in ways that people who live in rural areas cannot, and often travelling to larger centres for these services is not possible. Moreover, rural, heterosexual white Americans often don’t see themselves as at risk, even though they engage in risky behaviours, including intravenous drug use.

All these problems are further confounded because many of the rural counties that are hotspots for HIV and are increasingly threatened by coronavirus are also battling the opioid epidemic.

What we can learn from HIV that is relevant to coronavirus?

- Testing — with contact tracing and follow-up to ensure this has happened and people who are receiving appropriate treatment and information — is imperative to prevent transmission and pressures on the health care system and save lives.

- The concept of risk groups is dangerous. HIV doesn’t discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation but on the basis of sexual behaviours and activities that involved the transfer of infected blood. Coronavirus does not infect only the elderly and the sick but can strike down young, healthy individuals.

- Long-term commitments to and investments in research, public health, and strategic planning for such pandemics pay off. Failure to do this means that governments start off on the back foot.

- The coronavirus pandemic is accompanied by what WHO describes as an “infodemic” of misinformation, disinformation, conspiracy theories and myths. Just as in the early HIV/AIDS years, science is too often, for too many people, on the back foot. The situation in 2020 is aggravated by the use of social media to spread this infodemic. Clear public guidance, tailored as appropriate to different population groups and evidence-based, is needed to address the inevitable myths, anti-science responses, spurious preventatives and cures that arise and fuel public fears and suspicions.

- The measures put in place to limit social contacts during the coronavirus pandemic have been shown in some countries to be effective in also limiting the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In the United Kingdom, sexual health specialists believe the unique set of circumstances lockdown has created offers an unprecedented opportunity in the decades-long fight against HIV too. There are efforts to get people at risk for HIV tested, through postal testing services, and then into treatment before they emerge from lockdown and resume normal sexual activity. New Zealand has also seen the opportunity that lockdown has provided to “break the chain” and is scaling up testing to find New Zealanders living with undiagnosed AIDS and STIs. Sadly, the widespread failure to implement social isolation and quarantine procedures in the United States means that such opportunities are dramatically reduced.